Twin sisters Judith and Joyce Scott’s life story sounds straight out of a movie.

It’s a story with everything you’d imagine in an Oscar-winning movie: an idyllic childhood, heart-shattering loss, an emotional reunion followed by triumph, and resounding artistic acclaim. Above all, it’s two sisters who loved each other beyond adversity and through everything. And it’s 100% true.

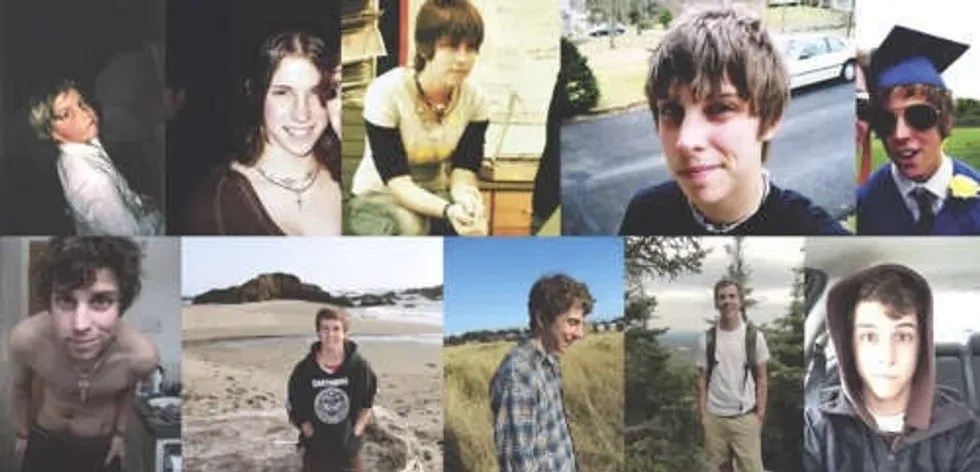

Twin sisters Judith (right) and Joyce Scott as infants. All images via Joyce Scott, used with permission.

Joyce and Judith were born in Cincinnati in 1943. Judith had Down syndrome and Joyce did not. The sisters were loving and devoted to each other.

For the first seven years of their lives, they spent most of their days playing in a sandbox made just for the two of them. They slept in the same bed at night.

But their parents grew overwhelmed and desperate. They didn’t know how to interact with Judith. Along with Down syndrome, she couldn’t speak and had undiagnosed deafness. The medical community at the time knew very little about how to engage children with Down syndrome and recommended institutionalizing her. Her parents gave in.

At age 7, Judith was sent to live in a sanitarium. She remained there for the next 25 years.

During that time, her sister Joyce grew up. But she couldn’t shake the memories of her sister.

By the time she was 25, Joyce had graduated from college, moved to California, and started work as a nurse specializing in care for children with developmental disabilities. She befriended the mother of one of her patients, joining her on silent meditation retreats. Five days into a six-day retreat, Joyce had an epiphany.

“I had this feeling that I was there with Judy and that our core was a central core that we shared. It was like someone turning on the light in a dark room. It became clear to me: ‘What on earth is she doing in an institution 2,000 miles away when she could be with us?’” Joyce told an interviewer last year.

Just like that, Joyce’s life changed. She assumed guardianship of her sister and brought her home to California. Their family was finally whole again.

As the sisters adapted to their new life, Joyce learned about Creative Growth, an enrichment center for developmentally disabled adults.

Judith and Joyce Scott.

She began taking Judith there five days a week for painting and drawing classes, hoping something would spark her creativity.

For two years, nothing clicked. Then one day, a textile artist came to give a presentation. Judith was transfixed. She picked up two sticks and began slowly, methodically wrapping them in strips of fabric.

That wrapped bundle became her first sculpture. Over the next 18 years, she would create more than 200 more.

Judith’s talent was rare and immediately apparent.

Her sculptures defy convention and definition. They’re simple and intricate, colorful and muted, commanding and gentle.

The unifying feature of Judith’s work is wrapped fabric. Her pieces range in size from tiny handheld sculptures that resemble dolls to huge installation pieces that cannot be moved without help. She wasn’t particular about her medium, working with whatever items were around the Creative Growth studio.

Nor was there a particular rhythm to her process. She worked exactly as long as a piece took to finish — whether that was an hour, a day, a week, even a month.

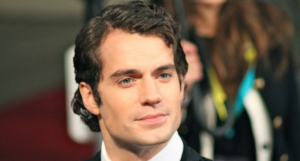

An exhibition of Judith’s work at a gallery in Brooklyn, New York.

Judith Scott had almost no interaction with her artworks once she finished them. The exception was when she saw them at her first art show. According to her sister, Judith wandered among the works and, one by one, kissed or hugged them. “There wasn’t a dry eye in the house,” recalls Joyce.

It didn’t take long before people started to notice Judith’s talent.

In 1999, Creative Growth held the first showing of Judith’s work to coincide with the release of the first book about her. It drew worldwide attention, which meant more admirers and more books for Judith, along with documentaries and news articles.

Judith was both nonverbal and illiterate, with no way to share the inspiration behind her creations. Everything — even the names of the artworks themselves — is up to the viewer’s interpretation.

“Judith’s sculptures, objects, things are, to my mind, amongst the most important three-dimensional things made in the last century. There is no question or doubt about it.”

— Matthew Higgs, former director of exhibitions at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts

Critics have tried to define Judith’s art, calling it “outsider art” or “brutalist.” But her art stands on its own out of necessity. She told her story through wrapped objects and knotted fabric, rather than words and sentences.

In 2005, one evening after dinner, Judith passed away peacefully in her sister’s arms. For the past 11 years, Joyce has continued to tell her story.

In addition to her work helping other artists with disabilities around the world, Joyce has joined exhibitions of Judith’s work and written a book about their life together.

Many people credit Joyce with transforming her sister’s life, but she disagrees. Judith, she says, was her guardian and caretaker, not the other way around.