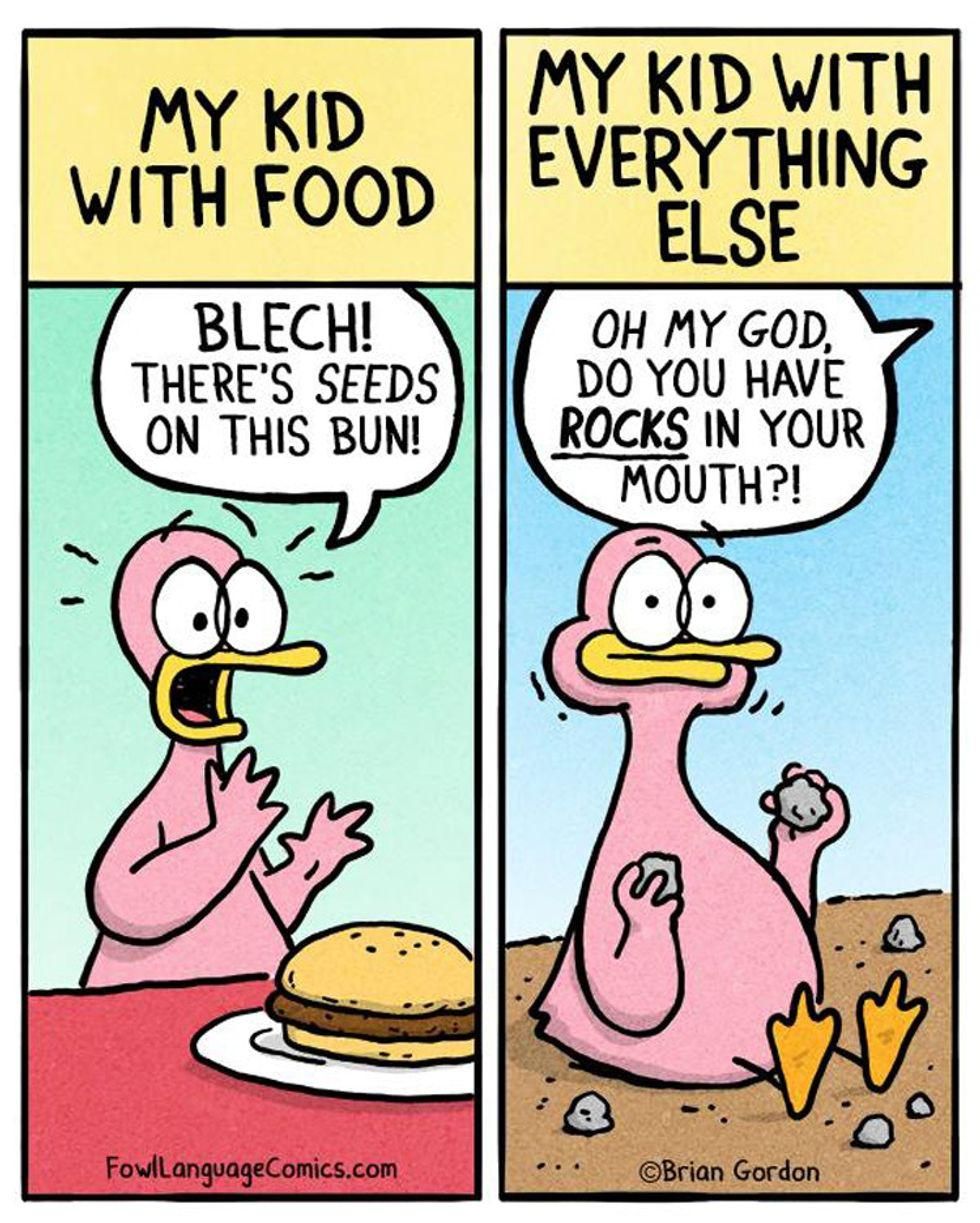

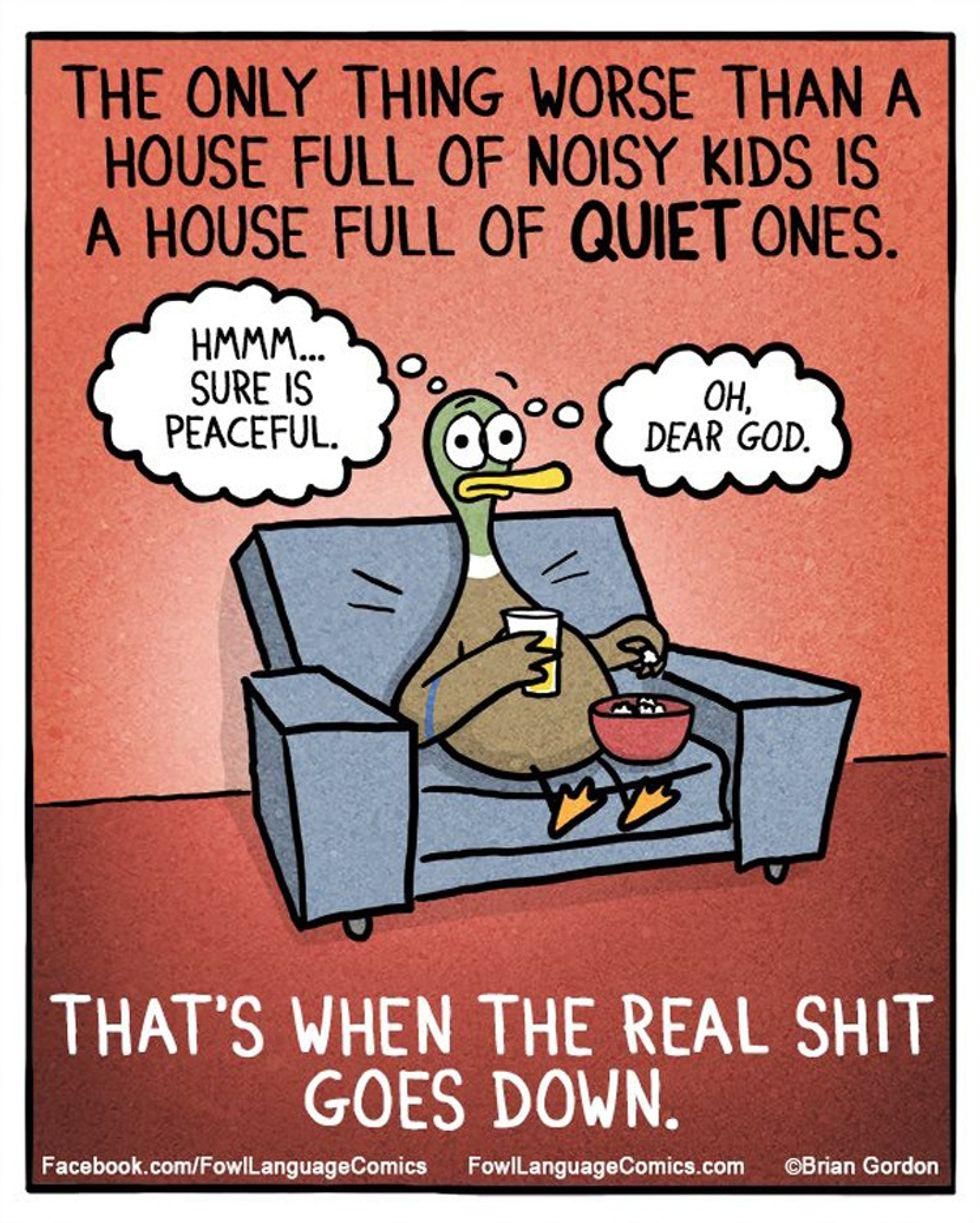

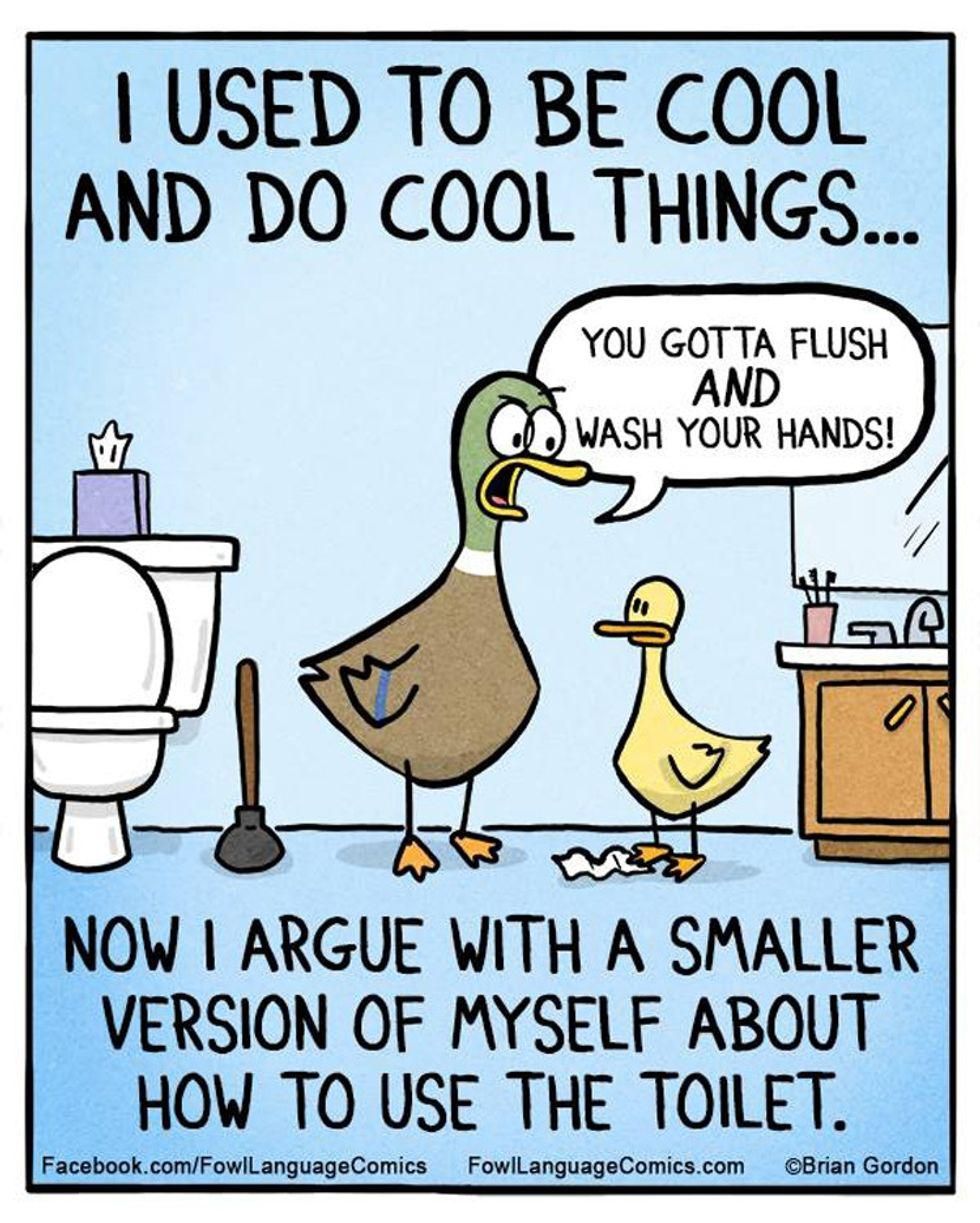

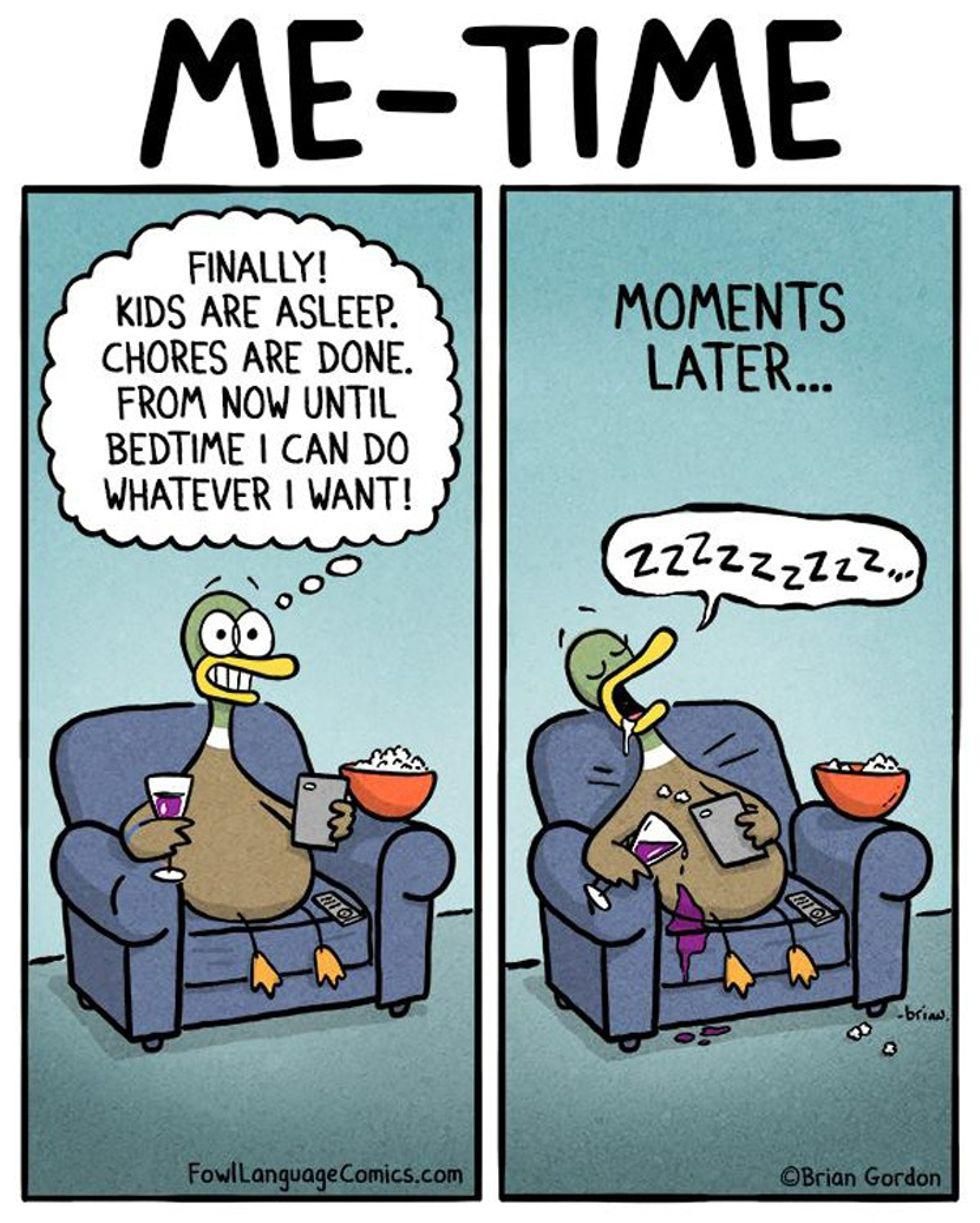

15 hilarious parenting comics that are almost too real

They're funny because they're true.

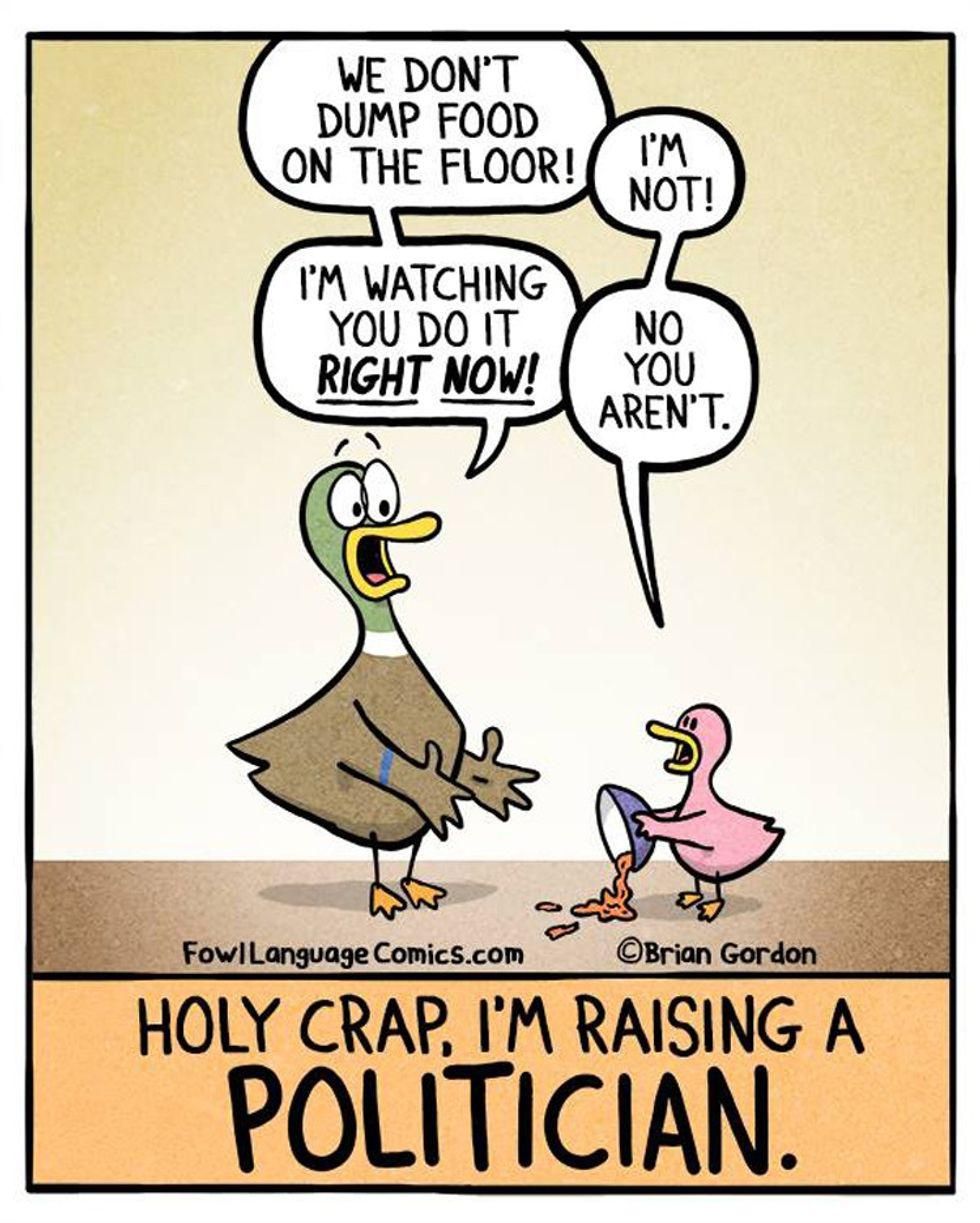

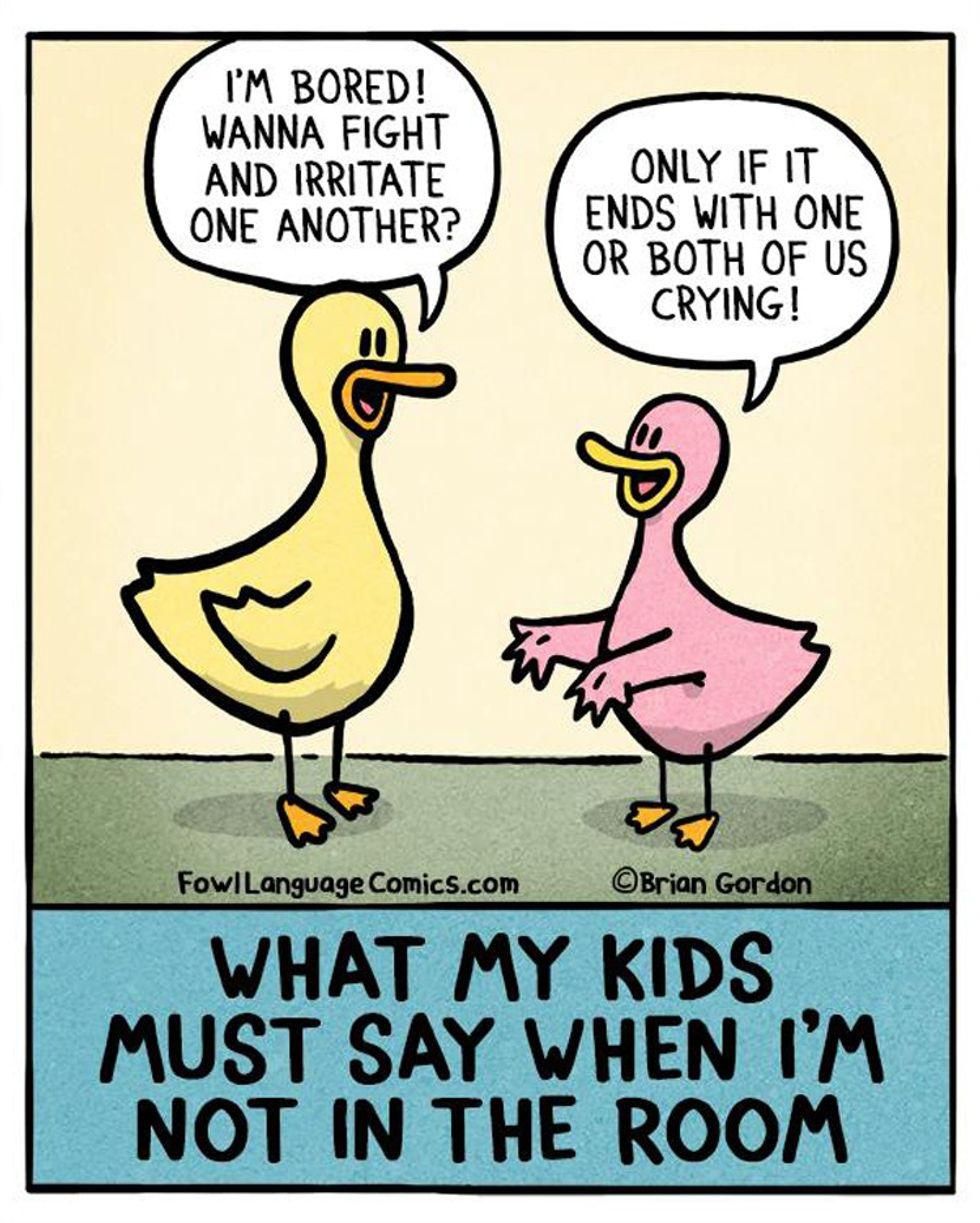

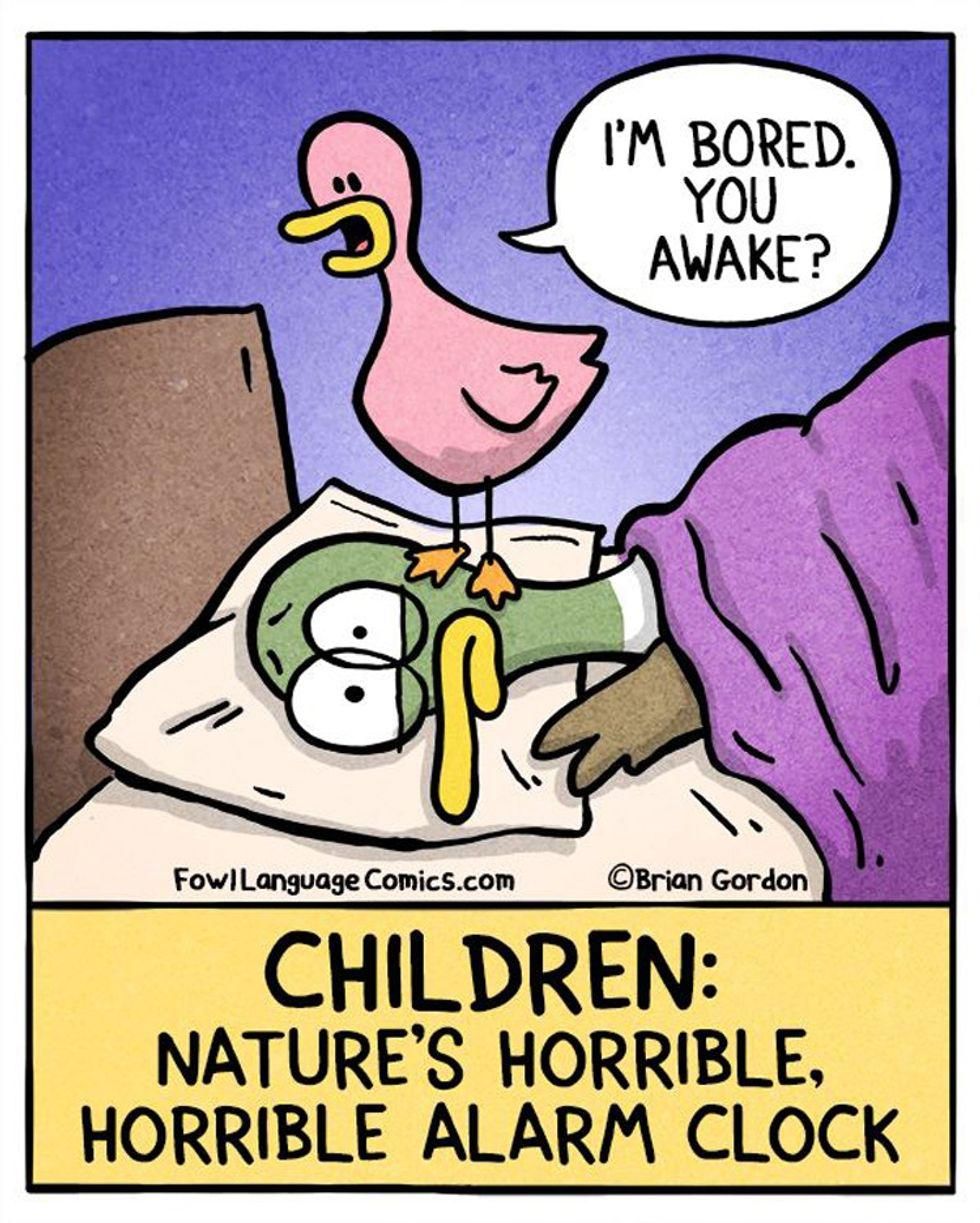

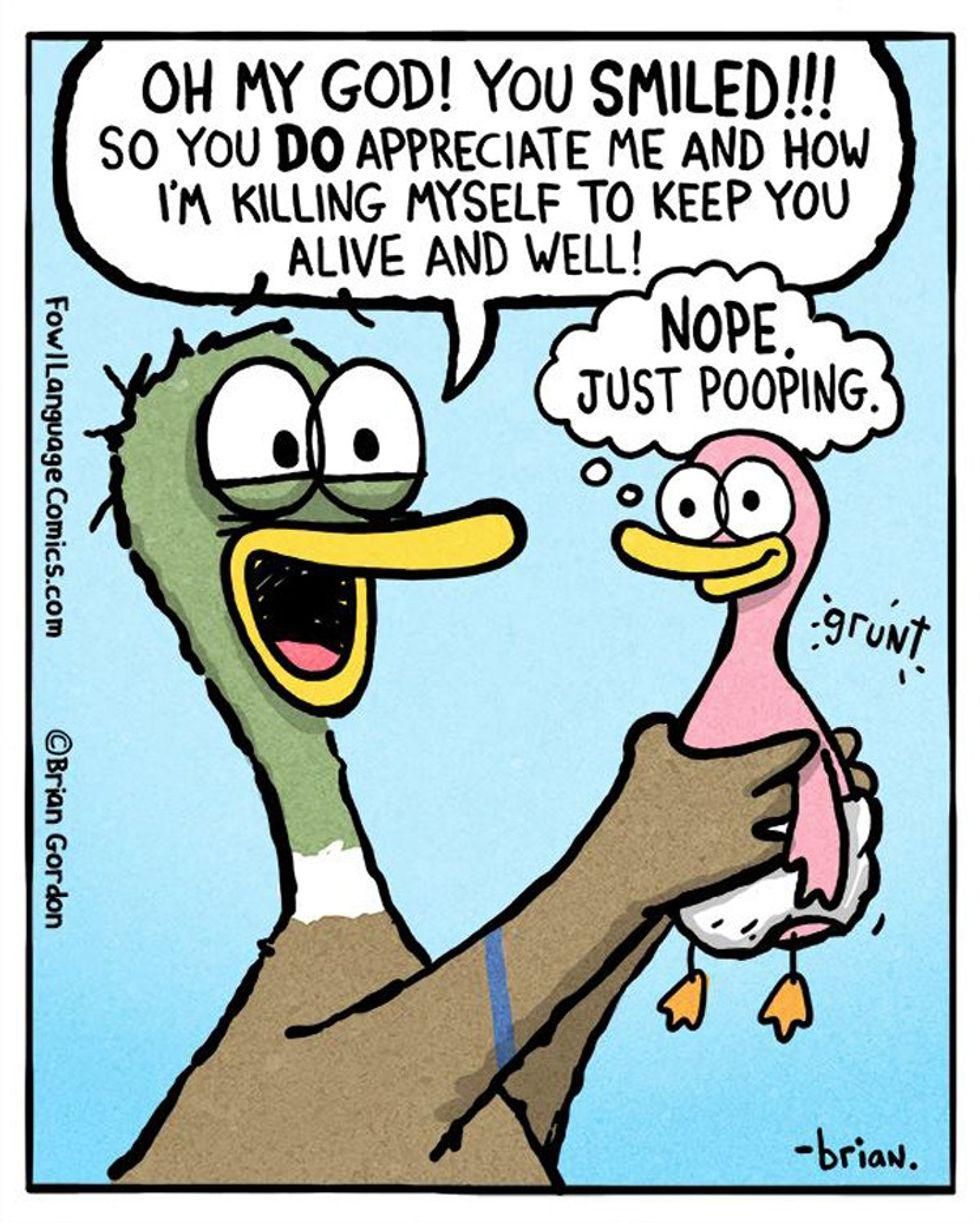

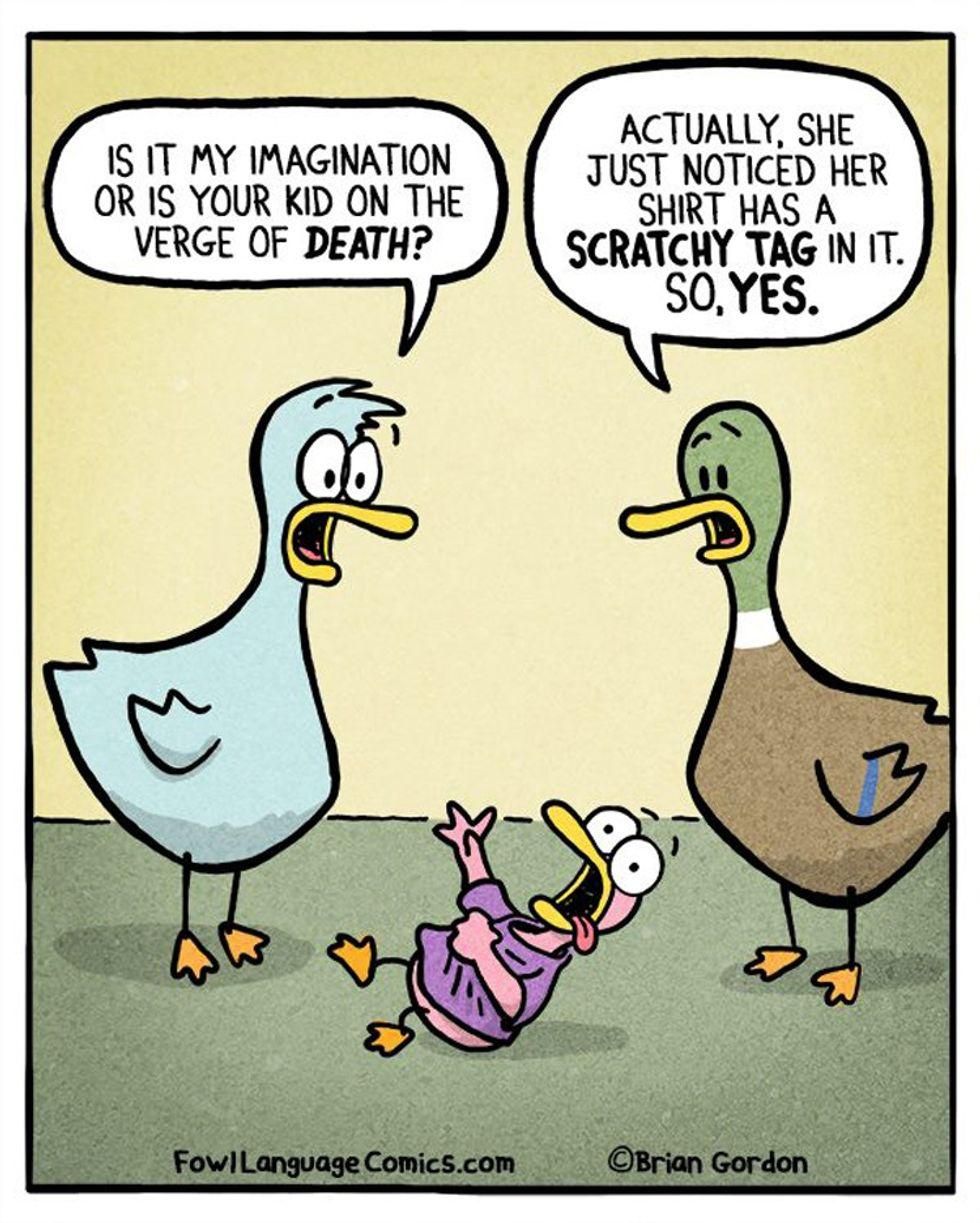

Fowl Language by Brian Gordon

Brian Gordon is a cartoonist. He's also a dad, which means he's got plenty of inspiration for the parenting comics he creates for his website, Fowl Language (not all of which actually feature profanity). He covers many topics, but it's his hilarious parenting comics that are resonating with parents everywhere.

"My comics are largely autobiographical," Gordon tells me. "I've got two kids who are 4 and 7, and often, what I'm writing happened as recently as that very same day."

Gordon shared 15 of his oh-so-real comics with us. They're all funny 'cause they're true.

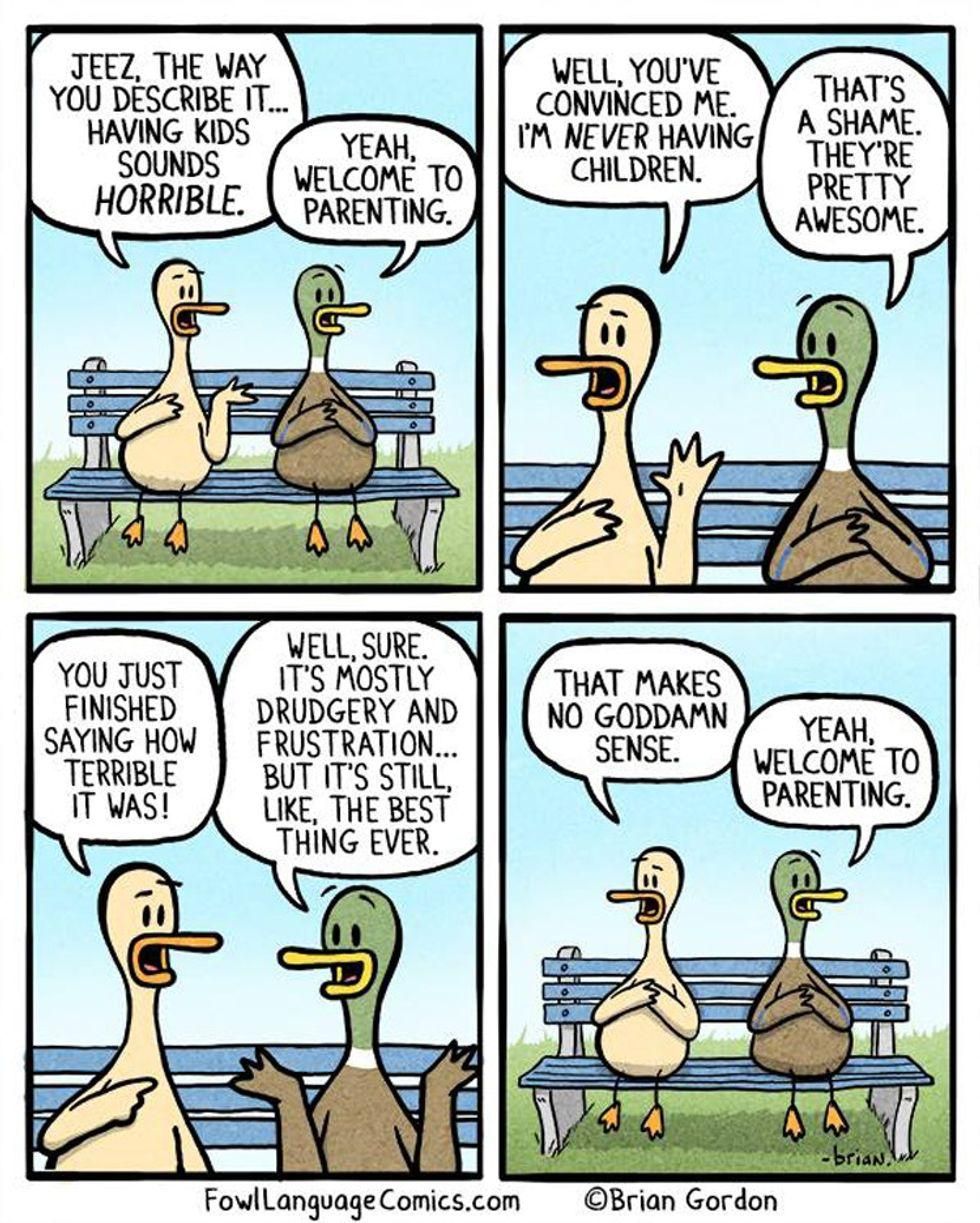

Let's get started with his favorite, "Welcome to Parenting," which Gordon says sums up his comics pretty well. "Parenting can be such tedious drudgery," he says, "but if it wasn't also so incredibly rewarding there wouldn't be nearly so many people on the planet."

Truth.

I hope you enjoy these as much as I did.

1.

“Welcome to parenting."

via Fowl Language

All comics are shared here with Gordon's express permission. These comics are all posted on his website, in addition to his Facebook page. You can also find a "bonus" comic that goes with each one by clicking the "bonus" link. Original. Bonus.

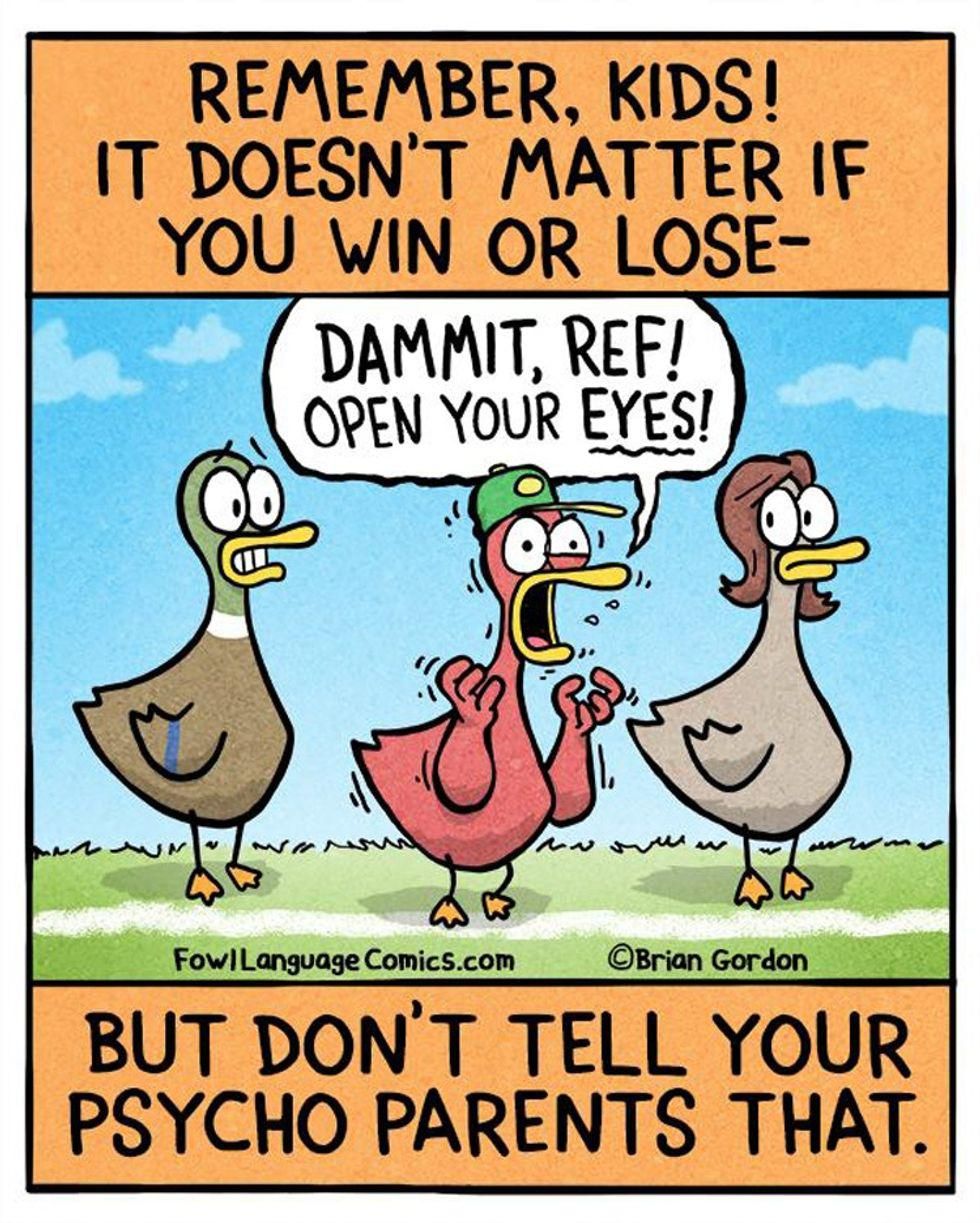

2.

Perception shifts.

via Fowl Language

I love Gordon's comics so much because they're just about the reality of parenting — and they capture it perfectly.

There's no parenting advice, no judgment, just some humor about the common day-to-day realities that we all share.

When I ask him about the worst parenting advice he's ever received, Gordon relays this anecdote:

"I remember being an absolute sleep-deprived wreck, sitting outside a sandwich shop, wolfing down my lunch quickly beside my 1-month-old son, who was briefly resting his lungs between screaming fits.

A rather nosy woman walked up to me and said, all smugly, 'You should enjoy this time while they're easy.' It was the exact worst thing anyone could have said to me in that moment and I just wanted to curl up on the sidewalk and cry."

Who hasn't been on the receiving end of totally unneeded and unwanted advice? That's why Gordon's comics are so welcome: They offer up a space for us to all laugh about the common experiences we parents share.

Here's to Gordon for helping us chuckle (through the tears).

This article originally appeared nine years ago.

- Mom's comics illustrate the parenting double standard - Upworthy ›

- Nine things new parents think they need and practical alternatives - Upworthy ›

- Child development Phd shares parenting advice - Upworthy ›

- 10 things that made us smile this week - Upworthy ›

- Woman finds out daughter is labeled a 'flight risk' at school - Upworthy ›

- Little girl shocks her mom by pulling out a pocket full of worms - Upworthy ›

- Dad tells child their mom has rabies in funny misunderstanding - Upworthy ›

- Mom shares wild story of how her daughter kidnapped a baby - Upworthy ›

- Mom shares PSA on about being a sports mom while also working - Upworthy ›

- Woman calls cops on another parent and regrets it - Upworthy ›

- Her boyfriend asked her to draw a comic about their relationship. Hilarity ensued. - Upworthy ›

- Mom teaches daughter a perfect lesson after she threw her new pencil case in the trash. - Upworthy ›

- Mom shares a really unique 'anxiety attack' approach for dealing with toddler tantrums - Upworthy ›

- Dad shares an 'Amazon product review' of his newborn baby and it's parody perfection - Upworthy ›

- Dad shares an 'Amazon product review' of his newborn baby and it's parody perfection - Upworthy ›