Some black people use the n-word, so why the uproar when a white person says it?

Discussion of the term has peaked again with Papa John’s founder John Schnatter resigning after Forbes reported he used the n-word during a media training. “Colonel Sanders called blacks n—–s,” Schnatter said, complaining that the KFC founder never received backlash for it. He later issued an apology, but the damage was done.

The pizza tycoon is not alone in haphazardly wielding the n-word. Paula Deen, Madonna, Charlie Sheen, and others have faced scrutiny for using the term, in each case prompting some white people to start questioning who should and shouldn’t use it.

Here are some explanations from black folks for why the n-word needs to be off the table for nonblack people.

Ta-Nehisi Coates explained how words can be appropriate or not depending on our relationships.

In 2017, a high school student asked Coates about her white friends singing the n-word as hip-hop lyrics. Coates explained that who you are matters, pointing out that even though his wife calls him “honey,” it wouldn’t be acceptable for a strange woman on the street to call him that. “The understanding is that I have some sort of a relationship with my wife,” he said. “Hopefully, I don’t have a relationship with this strange woman.”

He also gave several examples of how certain words are used within groups that aren’t appropriate for people outside the group. Sometimes his wife’s friends will use the word “bitch” in a funny, ironic way toward one another, but Coates doesn’t join in. “And perhaps more importantly, I don’t have a desire to,” he said.

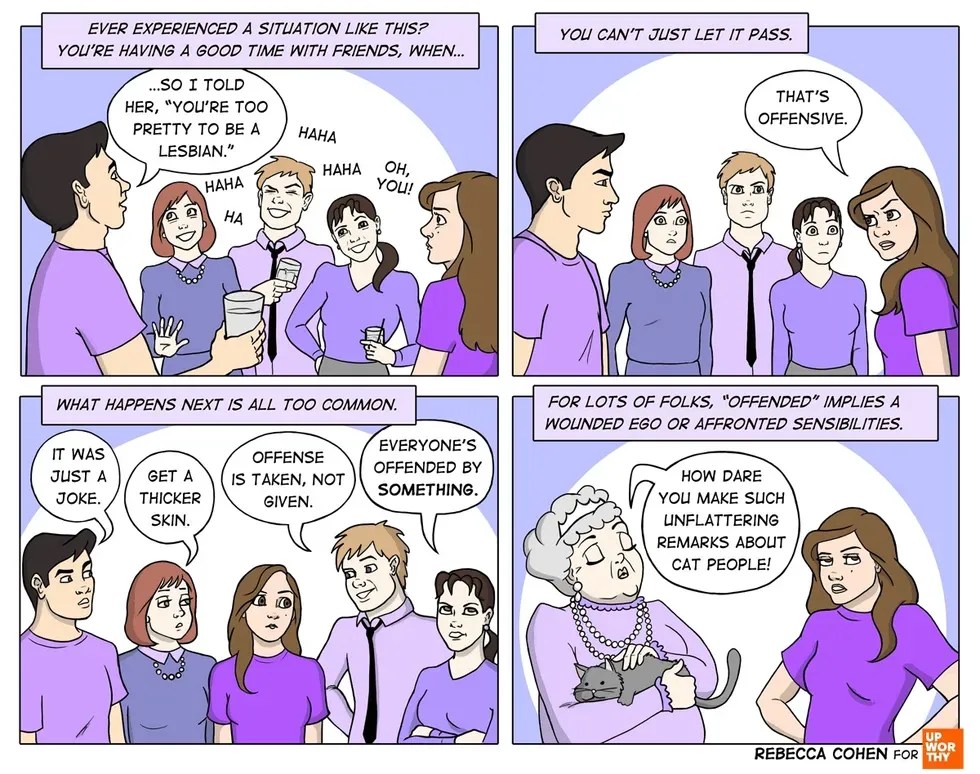

“We understand that it’s normal, actually, for groups to use derogatory terms in an ironic fashion,” he continued. “Why is there so much hand-wringing when black people do it?”

Franchesca Ramsey broke down the origin of the word and explained why the history of it matters.

“The n-word comes from the Spanish and Portuguese word for black — ‘negro,’” Ramsey explained in a YouTube video:

“How do you take a completely benign word — the word for ‘black’— and make it into a slur? Well, you have to look at the word’s historical context. The n-word was used to describe black people as they were being stolen from Africa, put into slavery, chained, lynched, beaten, spit upon — so the word was created as a tool of oppression. Its historical context cannot be erased.”

Ramsey also touched on how relationships give context for certain behaviors. Football players regularly swat one another on the butt on the field as a form of encouragement, she said, but doing the same to a random person on the street is never OK.

We apply different standards to different groups of people all the time — without claiming that it’s unfair.

Michael Harriot used the analogy of someone making themselves a little too “at home” in your house.

In a hypothetical conversation between two black people, Michael Harriot of The Root explained why the n-word is taken differently when white folks use it:

“But if white people are racist when they use it, then why isn’t it racist when we use it? Take the woman who was onstage with Kendrick Lamar. How can you call her a racist if she uses the n-word in the same exact context Lamar did? It’s just a song, right?

OK. Suppose you came home one day and found someone naked, asleep in your bed. Would you be OK with that?

Of course not.

What if they gained entry because you inadvertently left the door unlocked?

I still wouldn’t be cool with it.

OK. Let’s say you invited someone to your house to watch the game. Instead of knocking, they waltzed in the unlocked door, got naked, took a shit in your bathroom, and crawled in your bed. That would be OK, right?

Absolutely not. People really shit in other people’s houses? That’s nasty and disrespectful.

Why? I bet you’ve done it a million times. How are they being disrespectful if they are only doing the same thing you do all the time?

Because it’s my house. Every idiot knows that.

Exactly.”

Bottom line: As a white person, I don’t have the right to use that word — nor do I have the right to tell black folks how to use it.

The n-word is a verbal weapon that was created by white people specifically to harm black people as part of their systematic oppression. That’s its origin. We can’t change that.

If a black person feels empowered in owning or reclaiming that weapon, it’s not my place to say they shouldn’t. But seeing that weapon displayed in the home of a white person would have an entirely different feel. One is the historical oppressor and the other is the historically oppressed, and that changes what’s appropriate for each.

Some feel that no one should use the n-word, and there is ongoing debate among the black community about the word. But that’s not a discussion for white people to insert ourselves into. We don’t need to weigh in on this. It’s not our debate to have.

The idea that some things don’t belong to us is a weird thing for many white people to wrap our brains around.

Whether consciously or subconsciously, white folks tend to assume that we get to make the rules for everyone. We’ve always held that power, and we’re used to having the final say. That’s part of the legacy of white supremacy.

The sentiment “If we can’t say it, nobody should be able to” is also an extension of white supremacy, and we need to let it go. When a word represents centuries of pain inflicted upon an entire group of people, let’s be humble enough to acknowledge that our feelings and opinions are far less important than those directly affected by it.

That seems only fair.