All images by Angelo Merendino, published here with permission.

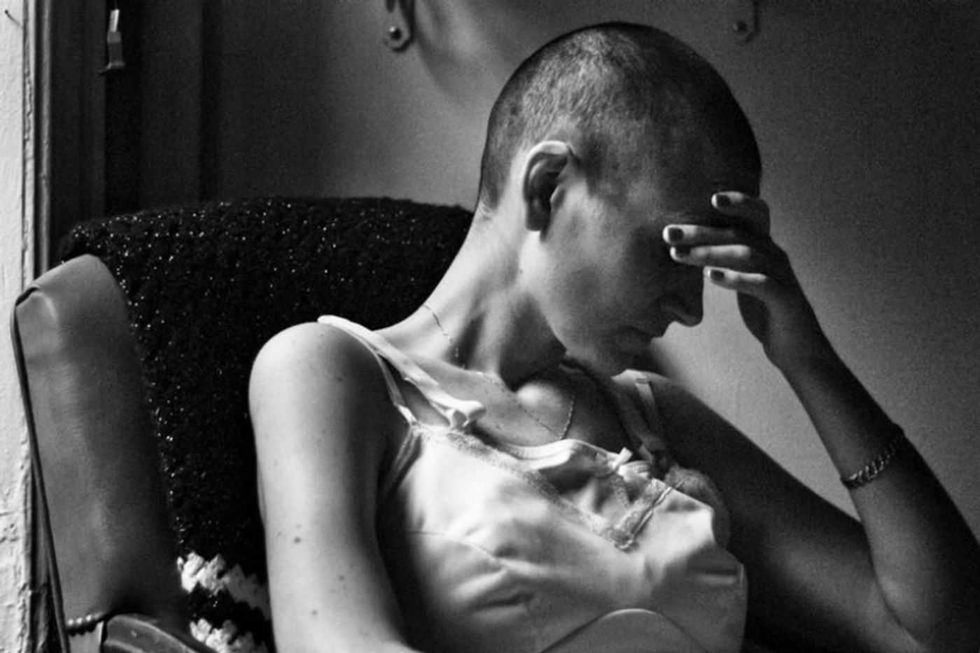

Cancer is unfortunately common, but seeing someone's cancer journey from start to finish is pretty uncommon. Medical experiences are often kept private, for understandable reasons, so the public is usually shielded from the various ups and downs and the intimate moments of pain and struggle, as well as love and even joy, that come along with battling terminal cancer.

When I first saw the incredible photos Angelo Merendino took of his wife, Jennifer, as she battled breast cancer, I felt that I shouldn't be seeing this snapshot of their intimate, private lives. The photos humanize the face of cancer and capture the difficulty, fear, and pain that they experienced during the difficult time.

Angelo and Jennifer were a happy couple.Angelo Merendino

Angelo and Jennifer were a happy couple.Angelo Merendino

But as Angelo commented: "These photographs do not define us, but they are us."

In his photo exhibition, Angelo wrote:

"Jennifer was diagnosed with breast cancer five months after our wedding. She passed less than four years later. During our journey we realized that many people are unaware of the reality of day to day life with cancer. After Jen’s cancer metastasized we decided to share our life through photographs."

Angelo and Jennifer Angelo Merendino

Angelo and Jennifer Angelo Merendino

Jennifer was diagnosed with cancer in 2008.Angelo Merendino

Jennifer was diagnosed with cancer in 2008.Angelo Merendino

Her diagnosis came only five months after they were married.Angelo Merendino

Her diagnosis came only five months after they were married.Angelo Merendino

On his website, Angelo writes:

"With each challenge we grew closer. Words became less important. One night Jen had just been admitted to the hospital, her pain was out of control. She grabbed my arm, her eyes watering, 'You have to look in my eyes, that’s the only way I can handle this pain.' We loved each other with every bit of our souls. Jen taught me to love, to listen, to give and to believe in others and myself. I’ve never been as happy as I was during this time."

However, the ups and downs of cancer journeys eventually take a toll. Having support is vital, but that doesn't mean everyone will understand or be able to be there the way we might hope.

Losing hair is a common side effect of cancer treatment.Angelo Merendino

Losing hair is a common side effect of cancer treatment.Angelo Merendino

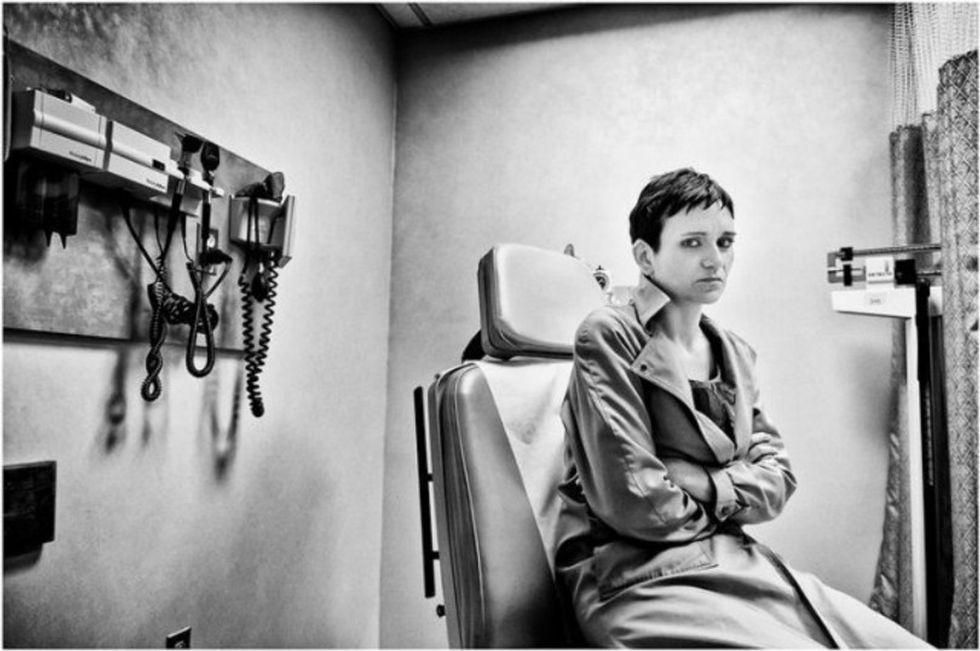

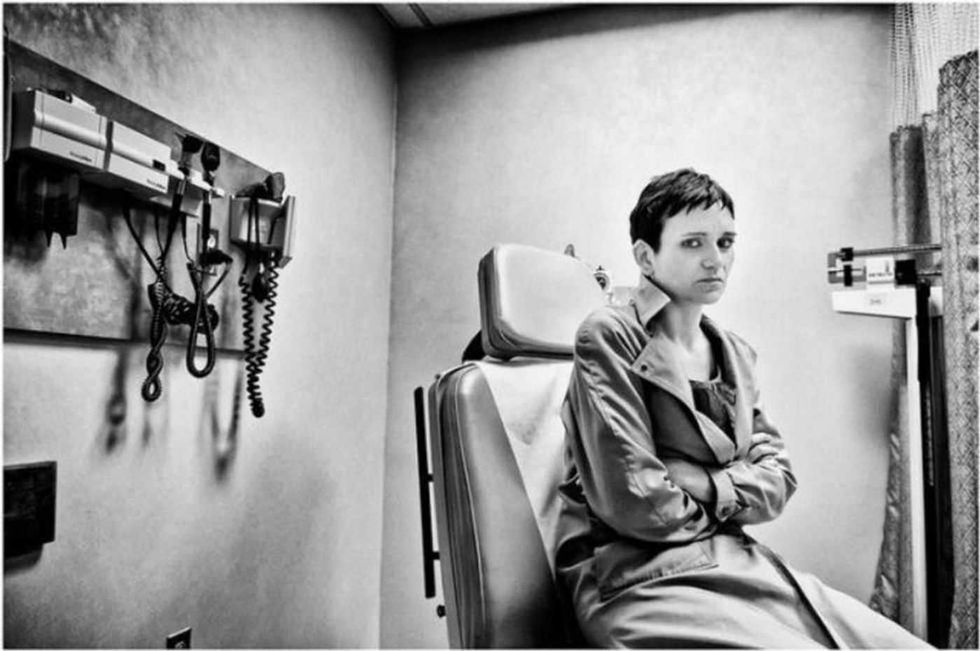

Angelo and Jennifer decided to document her cancer journey.Angelo Merendino

Angelo and Jennifer decided to document her cancer journey.Angelo Merendino

“Throughout our battle we were fortunate to have a strong support group but we still struggled to get people to understand our day-to-day life and the difficulties we faced…

Sadly, most people do not want to hear these realities and at certain points we felt our support fading away.”

Cancer can be lonely sometimes. Angelo Merendino

Cancer can be lonely sometimes. Angelo Merendino

"People assume that treatment makes you better, that things become OK, that life goes back to 'normal,' Angelo wrote. "There is no normal in cancer-land. Cancer survivors have to define a new sense of normal, often daily. And how can others understand what we had to live with everyday?"

Not everyone understands the journey.Angelo Merendino

Not everyone understands the journey.Angelo Merendino

They captured the ups and the downs. Angelo Merendino

They captured the ups and the downs. Angelo Merendino

They also captured the love and heartbreak.Angelo Merendino

They also captured the love and heartbreak.Angelo Merendino

“When people see these photographs, I hope they see life before death,” Angelo writes. “I hope they see love before loss.”

Small joys are part of the journey.Angelo Merendino

Small joys are part of the journey.Angelo Merendino

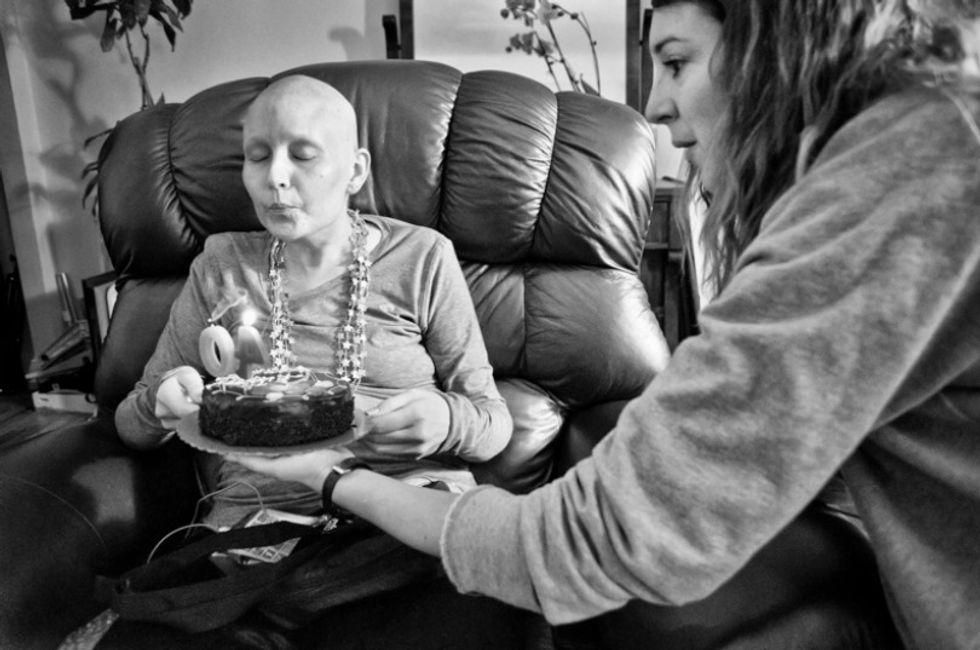

Celebrating Jennifer's 40th birthdayAngelo Merendino

Celebrating Jennifer's 40th birthdayAngelo Merendino

Having a support system makes a big difference. Angelo Merendino

Having a support system makes a big difference. Angelo Merendino

Every photo tells a story.Angelo Merendino

Every photo tells a story.Angelo Merendino

There is love in every image.Angelo Merendino

There is love in every image.Angelo Merendino

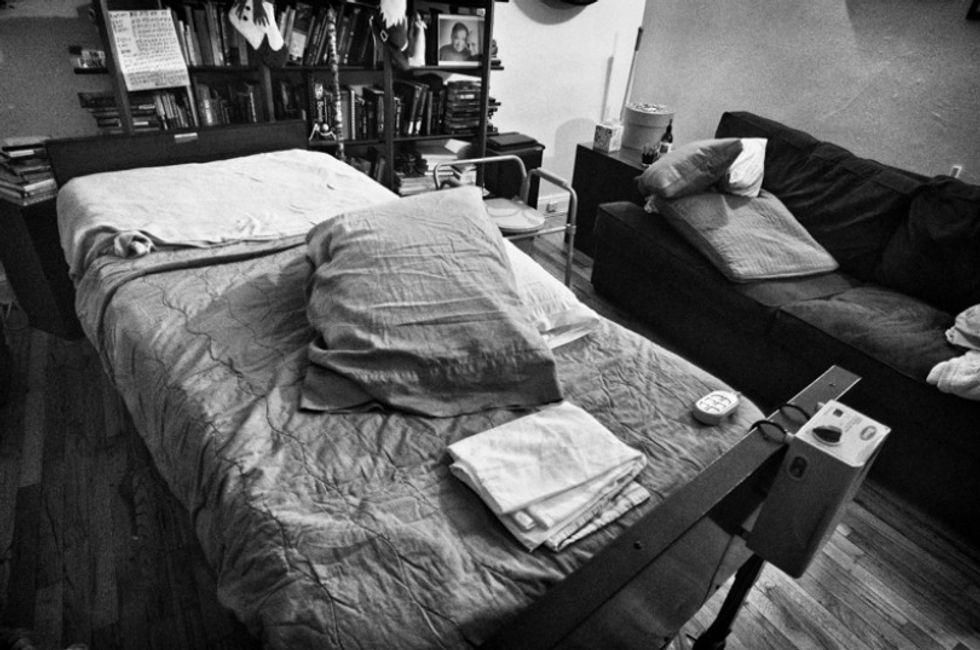

And then the after began.Angelo Merendino

And then the after began.Angelo Merendino

Jennifer passed in 2011, and Angelo has had his own long healing journey in the years since. He told the Susan G. Komen Foundation in 2022 that finding a therapist who had lost a spouse helped him a lot.

“Healing has been an ongoing thing. I don’t want to forget how much it hurts, because I think the other side of that is how much I loved Jen, and how much she loved me,” Angelo said. “I try to remember how fortunate I am to be alive and to not take for granted all the things that I have in my life.”

Jennifer's tombstone reads "I loved it all." Angelo Merendino

Jennifer's tombstone reads "I loved it all." Angelo Merendino

“If you’re going through this, keep moving forward,” Angelo said. “Be graceful with yourself. Know you you’ll find joy again. Something as simple as a sunset will make you more thankful than anything. There’s still so much life to live. Out of honor to Jen, I have to live my life again.

This article originally appeared thirteen years ago.

A woman is getting angry at her coworker.via

A woman is getting angry at her coworker.via  A man with tape over his mouth.via

A man with tape over his mouth.via  A husband is angry with his wife. via

A husband is angry with his wife. via

Curling requires more athleticism than it first appears.

Curling requires more athleticism than it first appears.

Angelo and Jennifer were a happy couple.

Angelo and Jennifer were a happy couple. Angelo and Jennifer

Angelo and Jennifer  Jennifer was diagnosed with cancer in 2008.

Jennifer was diagnosed with cancer in 2008. Her diagnosis came only five months after they were married.

Her diagnosis came only five months after they were married. Losing hair is a common side effect of cancer treatment.

Losing hair is a common side effect of cancer treatment. Angelo and Jennifer decided to document her cancer journey.

Angelo and Jennifer decided to document her cancer journey. Cancer can be lonely sometimes.

Cancer can be lonely sometimes.  Not everyone understands the journey.

Not everyone understands the journey. They captured the ups and the downs.

They captured the ups and the downs.  They also captured the love and heartbreak.

They also captured the love and heartbreak. Small joys are part of the journey.

Small joys are part of the journey. Celebrating Jennifer's 40th birthday

Celebrating Jennifer's 40th birthday Having a support system makes a big difference.

Having a support system makes a big difference.  Every photo tells a story.

Every photo tells a story. There is love in every image.

There is love in every image. And then the after began.

And then the after began. Jennifer's tombstone reads "I loved it all."

Jennifer's tombstone reads "I loved it all."

Comfort in a hug: a shared moment of empathy and support.

Comfort in a hug: a shared moment of empathy and support. A comforting hug during an emotional moment.

A comforting hug during an emotional moment. Woman seated against brick wall, covering ears with hands.

Woman seated against brick wall, covering ears with hands.