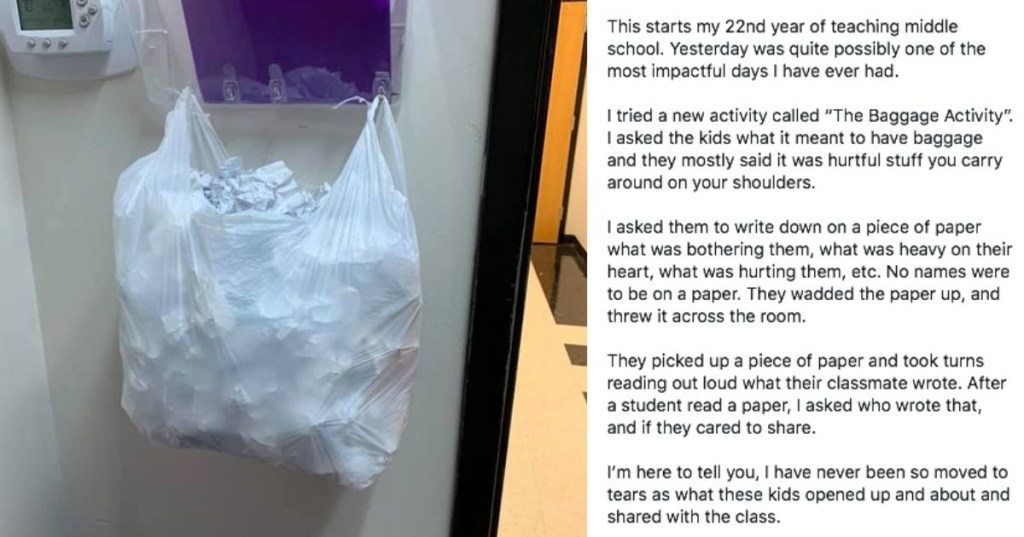

In the years following the bitter Civil War, a former Union general took a holiday originated by former Confederates and helped spread it across the entire country.

The holiday was Memorial Day, and the 2018 commemoration on May 28 marks the 150th anniversary of its official nationwide observance. The annual commemoration was born in the former Confederate States in 1866 and adopted by the United States in 1868. It is a holiday in which the nation honors its military dead.

Gen. John A. Logan, who headed the largest Union veterans fraternity at that time, the Grand Army of the Republic, is usually credited as being the originator of the holiday.

Yet when Logan established the holiday, he acknowledged its genesis among the Union’s former enemies, saying, “It was not too late for the Union men of the nation to follow the example of the people of the South.”

Cities and towns across America have for more than a century claimed to be the birthplace of Memorial Day.

But I and my co-author Daniel Bellware have sifted through the myths and half-truths and uncovered the authentic story of how this holiday came into being.

During 1866, the first year Memorial Day was observed in the South, a feature of the holiday emerged that made awareness, admiration and eventually imitation of it spread quickly to the North.

During the inaugural Memorial Day observances in Columbus, Georgia, many Southern participants — especially women — decorated graves of Confederate soldiers as well as those of their former enemies who fought for the Union.

Shortly after those first Memorial Day observances all across the South, newspaper coverage in the North was highly favorable to the ex-Confederates.

“The action of the ladies on this occasion, in burying whatever animosities or ill-feeling may have been engendered in the late war towards those who fought against them, is worthy of all praise and commendation,” wrote one paper.

On May 9, 1866, the Cleveland Daily Leader lauded the Southern women during their first Memorial Day.

“The act was as beautiful as it was unselfish, and will be appreciated in the North.”

The New York Commercial Advertiser, recognizing the magnanimous deeds of the women of Columbus, echoed the sentiment. “Let this incident, touching and beautiful as it is, impart to our Washington authorities a lesson in conciliation.”

To be sure, this sentiment was not unanimous. There were many in both parts of the U.S. who had no interest in conciliation.

But as a result of one of these news reports, Francis Miles Finch, a Northern judge, academic and poet, wrote a poem titled “The Blue and the Gray.” Finch’s poem quickly became part of the American literary canon. He explained what inspired him to write it:

“It struck me that the South was holding out a friendly hand, and that it was our duty, not only as conquerors, but as men and their fellow citizens of the nation, to grasp it.”

Finch’s poem seemed to extend a full pardon to the South: “They banish our anger forever when they laurel the graves of our dead” was one of the lines.

Almost immediately, the poem circulated across America in books, magazines and newspapers. By the end of the 19th century, school children everywhere were required to memorize Finch’s poem.

[rebelmouse-image 19398143 dam=1 original_size=”237×305″ caption=”Not just poems: Sheet music written to commemorate Memorial Day in 1870. Image via the Library of Congress.” expand=1]

As Finch’s poem circulated the country, the Southern Memorial Day holiday became a familiar phenomenon throughout America.

Logan was aware of the forgiving sentiments of people like Finch. When Logan’s order establishing Memorial Day was published in various newspapers in May 1868, Finch’s poem was sometimes appended to the order.

It was not long before Northerners decided that they would not only adopt the Southern custom of Memorial Day, but also the Southern custom of “burying the hatchet.”

A group of Union veterans explained their intentions in a letter to the Philadelphia Evening Telegraph on May 28, 1869:

“Wishing to bury forever the harsh feelings engendered by the war, Post 19 has decided not to pass by the graves of the Confederates sleeping in our lines, but divide each year between the blue and the grey the first floral offerings of a common country. We have no powerless foes. Post 19 thinks of the Southern dead only as brave men.”

Other reports of reciprocal magnanimity circulated in the North, including the gesture of a 10-year-old who made a wreath of flowers and sent it to the overseer of the holiday, a Col. Leaming in Lafayette, Indiana, with the following note attached, published in The New Hampshire Patriot on July 15, 1868:

“Will you please put this wreath upon some rebel soldier’s grave? My dear papa is buried at Andersonville, (Georgia) and perhaps some little girl will be kind enough to put a few flowers upon his grave.”

Although not known by many today, the early evolution of the Memorial Day holiday was a manifestation of Abraham Lincoln’s hope for reconciliation between North and South.

Lincoln’s wish was that there be “malice toward none” and “charity for all.” These wishes were clearly fulfilled in the magnanimous actions of citizens on both sides, who extended an olive branch during those very first Memorial Day observances.

This story originally appeared on The Conversation and is printed here with permission.