1974 interview about computers proves Arthur C. Clarke's predictions were eerily accurate

Arthur C. Clarke must've been from the future.

1974 interview about computers proves Arthur C. Clarke's predictions were accurate.

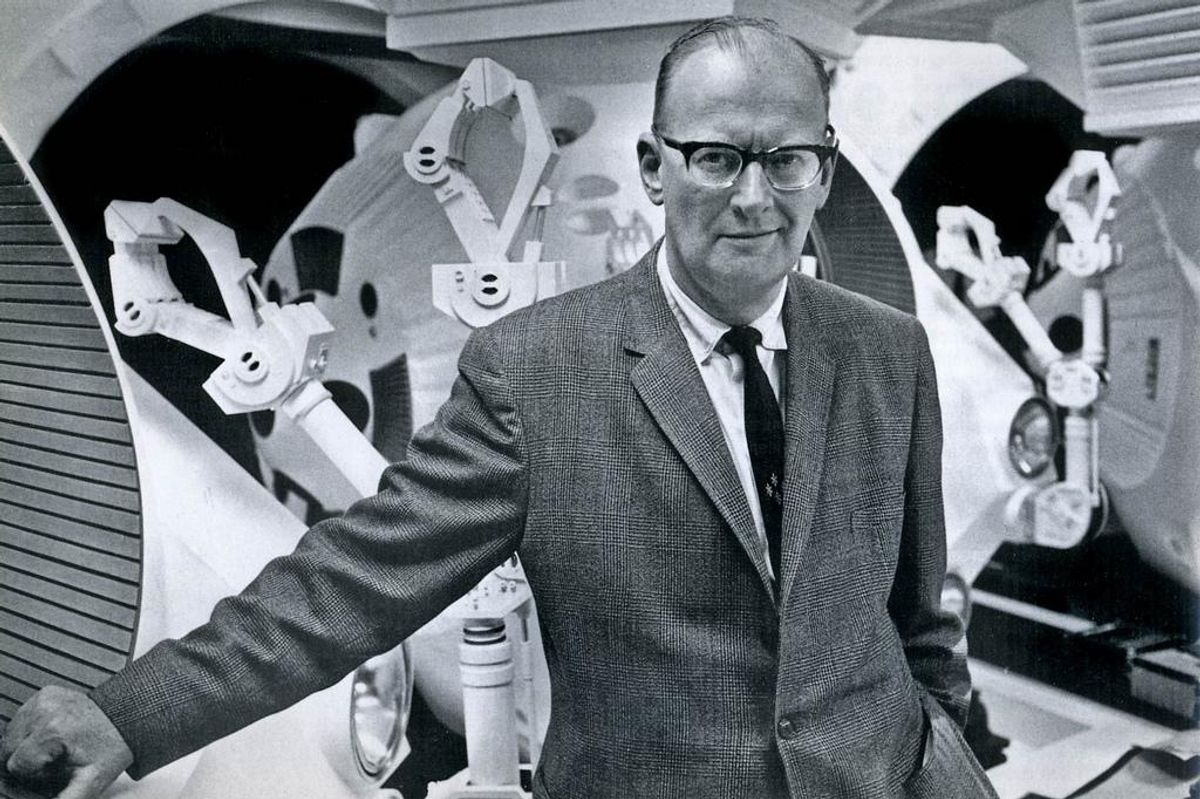

Science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke is best known for co-writing the screenplay for the 1968 movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, one of the most influential films of all time. But more than a science fiction writer, Clarke was also an explorer, a TV presenter, and a forward thinker who helped popularize science and space travel. In 1961, he won a UNESCO award for popularizing science.

Clarke, who died in 2008 at age 90, was ahead of his time and his contributions to the world of science fiction will continue to live on. A resurfaced 1974 interview with Clarke shows how forward thinking he truly was. In the interview, a young father and his son talk to Clarke about computers.

The father explains that in the year 2001, his son will be the same age as he (the father) is at the time of the recording of the video. Surrounded by mainframe computers, the father wants to know how computers will have changed by the time his son is an adult.

In the interview, Clarke predicts that the large machines he was showing off would be compact enough to sit on a desk at one's home, and that the man's son will be able to access "all the information he needs for his everyday life. His bank statements, theater reservations, all the information you need in the course of living in a modern, complex society." Clarke went on to say that computers would be taken for granted much like telephones. But the boy's father still had his concerns and surprisingly they're the same concerns of many parents today.

The father asked about the social implications of building everything around the computer and how it would impact individuals. Clarke must've had a crystal ball because he expanded on how it would enrich society and gave the example of workers such as business executives being able live anywhere on Earth and be able to work at home from their computers. Neat and a little creepy, huh?

Watch the uncanny prediction below:

- People are sharing endearing stories of how their elders use—and misuse—technology ›

- How Computers And Grandmothers Will Help Us Educate The Next 1 Billion Children ›

- One Time A Guy Gave A Homeless Man A Computer, And The Recipient Did Exactly What The Giver Expected ›

- In 1998, Americans predicted what life in 2025 would look like. Here's how they scored overall. - Upworthy ›