This anti-slavery feature of the Statue of Liberty is a symbol for how we treat our history

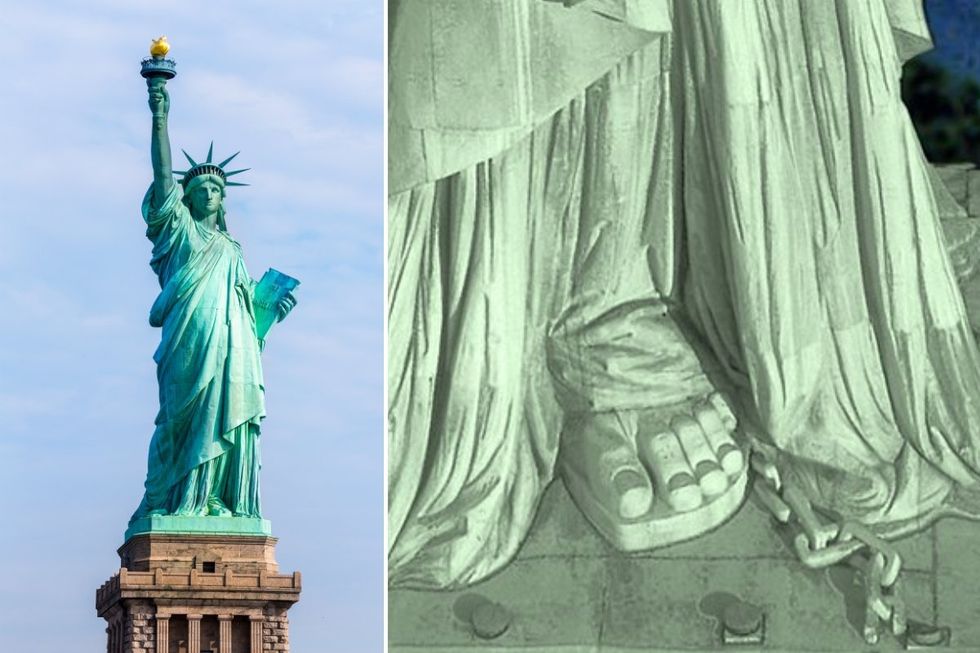

Lady Liberty's broken shackles are "hidden in plain sight."

The Statue of Liberty has broken shackles at her feet, which people can't really see.

If Americans were asked to describe the Statue of Liberty without looking at it, most of us could probably describe her long robe, the crown on her head, a lighted torch in her right hand and a tablet cradled in her left. Some might remember it's inscribed with the date of the American Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.

But there's a significant detail most of us would miss. It's a feature that points to why Lady Liberty was created and gifted to us in the first place. At her feet, where her robe drapes the ground, lay a broken shackle and chains—a symbol of the abolishment of slavery.

Most people see the Statue of Liberty as a symbol of our welcoming immigrants and mistakenly assume that's what she was meant to represent. Indeed, the opening words of Emma Lazarus's poem engraved on a plaque at the Statue of Liberty—"Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free"—have long evoked images of immigrants arriving on our shores, seeking a better life in The American Dream.

But that plaque wasn't added to the statue until 1903, nearly two decades after the statue was unveiled. The original inspiration for the monument was emancipation, not immigration.

According to a Washington Post interview with historian Edward Berenson, the concept of Lady Liberty originated when French anti-slavery activist—and huge fan of the United States' Constitution—Édouard de Laboulaye organized a meeting of other French abolitionists in Versailles in June 1865, just a few months after the American Civil War ended. "They talked about the idea of creating some kind of commemorative gift that would recognize the importance of the liberation of the slaves," Berenson said.

Laboulaye enlisted a sculptor, Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, to come up with ideas. One of the first models, circa 1870, had Lady Liberty holding the broken shackles and chains in her left hand. In the final iteration, her left hand wrapped around a tablet instead and the anti-slavery symbolism of the shackle and chain was moved to her feet.

Dr. Joy DeGruy, author of "Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America's Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing," often shares the story of how the chains were moved and how the shackles have been a neglected piece of Lady Liberty's history, even for those who visited the landmark. As she points out, both the shackles at her feet and the history of why they are there have been "hidden in plain sight."

Writer Robin Wright pondered in The New Yorker what Laboulaye would think of our country today. The America that found itself embroiled in yet another civil rights movement in 2020 because we still can't seem to get the whole "liberty and justice for all" thing down pat. The America that spent the century after slavery enacting laws and policies specifically designed to keep Black Americans down, followed by decades of continued social, economic and political oppression. The America that sometimes does the right thing, but only after tireless activism manages to break through a ton of resistance to changing the racism-infused status quo.

The U.S. has juggled dichotomies and hypocrisies in our national identity from the very beginning. The same founding father who declared "that all men are created equal" enslaved more than 600 human beings in his lifetime. The same people who celebrated religious freedom forced their Christian faith on Native peoples. Our most celebrated history of "liberty" and "freedom" is inseparable from our country's violent subjugation of entire races and ethnicities, and yet we compartmentalize rather than acknowledge that two things can be equally true at the same time.

Every nation on earth has problematic history, but what makes the U.S. different is that our problematic history is also our proudest history. Our nation was founded during the heyday of the transatlantic slave trade on land that was already occupied. The profound and world-changing document on which our government was built is the same document that was used to legally protect and excuse the enslavement of Black people. The house in which the President of the United States sits today was built partially by enslaved people. The deadliest war we've ever fought was over the "right" to enslave Black people.

The truth is that blatant, violent racism was institutionalized from the very beginning of this country. For most of us, that truth has always been treated as a footnote rather than a feature in our history educations. Until we really reckon with the full truth of our history—which it seems like we are finally starting to do—we won't ever get to see the full measure of what our country could be.

In some ways, the evolution of the design of the Statue of Liberty—the moving of the broken shackle and chain from her hands to being half hidden beneath her robe, as well as the movement of our perception of her symbolism from abolition to immigration—is representative of how we've chosen to portray ourselves as a nation. We want people to think: Hey, look at our Declaration of Independence! See how we welcome immigrants! We're so great! (Oh, by the way, hereditary, race-based chattel slavery was a thing for longer than emancipation has been on our soil. And then there was the 100 years of Jim Crow. Not to mention how we've broken every promise made to Native Americans. And honestly, we haven't even been that nice to immigrants either). But look, independence and a nod to immigration! We're so great!

The thing is that we can be so great. The foundation of true liberty and justice for all, even with all its cracks, is still there. The vision in our founding documents was truly revolutionary. We just have to decide to actually build the country we claim to have built—one that truly lives up to the values and ideals it professes for all people.

This article first appeared five years ago and has been updated.

- Why Was The Statue Of Liberty Built | Articles and News - Upworthy ›

- The Statue of Liberty is a symbol of welcoming immigrants. That wasn't what she was made for. ›

- In 1983, illusionist David Copperfield made the Statue of Liberty vanish. Here's how he did it. ›

- Ken Burns digs into bizarre Revolutionary War-era foods - Upworthy ›