A Palestinian and a Jewish stranger are showing people what a civilized conversation looks like

"I believe and I hope."

Two hands reach toward one another.

We live in challenging times, made even more divisive by social media rage. This is not to say that the rage is always uncalled for or unneeded, as there are many moments in history where even anger is righteous. But far more powerful in these times are the surprising moments of real connection, communication and understanding, like a recent exchange between a Palestinian and a Jewish stranger that shattered negative stereotypes and expectations.

I, like many, have become addicted to the algorithm, often fueled by propaganda, false narratives, and plain myopic anger. We are all, by nature, tribal ,and so many of our hearts have swelled with fear, sorrow, and an existential angst around the idea that humans simply might not be fixable.

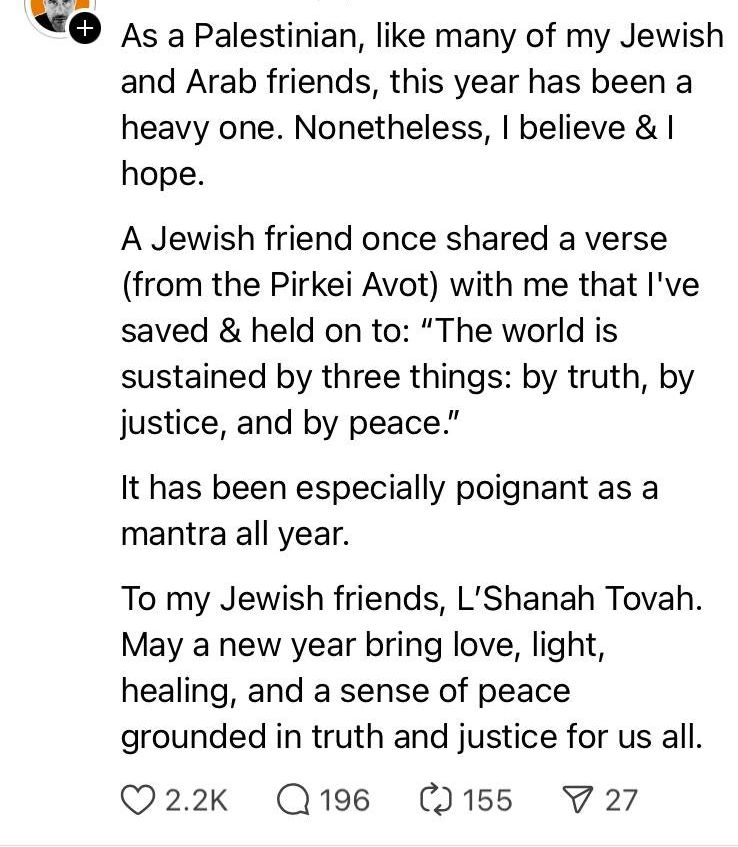

But I've noticed lately that I'm getting a stronger dopamine rush from reading supportive and kind comments as opposed to the hate-fueled ones. I stumbled upon a post on Threads from last year just before the Jewish New Year, (Rosh Hashana) which really struck me. A man wrote:

"As a Palestinian, like many of my Jewish and Arab friends, this year has been a heavy one. Nonetheless, I believe and I hope."

"A Jewish friend once shared a verse (from the Pirkei Avot) with me that I've saved and held on to: 'The world is sustained by three things: by truth, by justice, and by peace.'"

"It has been especially poignant as a mantra all year."

"To my Jewish friends, L'Shanah Tovah. May a new year bring love, light, healing, and a sense of peace grounded in truth and justice for all."

Having read this, I find myself constantly searching for like-minded people of all races, religions, and political affiliations who would also like to find a soft space nestled in this chaos. I scour social media sites and have found that often when you search, you find. It doesn't mean that there aren't literal and metaphorical fires burning all around us. It doesn't mean that we shouldn't stay informed and stand up for what we believe.

But, if just for a day, we could focus on these tiny victories, perhaps it's the smallest step to regaining our humanity. I happened upon a conversation last week (also on Threads) wherein a Palestinian woman made a comment about having pride in her heritage. Many nasty Islamophobic and anti-Semitic bots and trolls came out of the woodwork, but one comment stood out.

The OP wrote:

"All I said in my last post is 'I love being Palestinian' and the comments speak for themselves. We can’t love our heritage? Our culture? That’s too much for you (clown emoji)."

In response, someone wrote back:

"I’m Jewish. We probably disagree on lots, but to hell with those comments. You’re a human being deserving of respect, and to be proud of your culture and heritage."

The OP answered:

"Thank you for being rational. May we find a common middle ground one day."

This is met with:

"Hopefully in our lifetime! Don’t let the uneducated people bring you down."

A Threader pointed out, "This is one of the more mature comments I’ve seen. So much hate on these threads. Thank you for being a human being." The kindness began to multiply, with another person sharing, "That’s so true. I started a dialogue with a Jewish man and I would like to think we both learned a lot. You can’t understand how other people think and behave without respectful debates."

There are many more threads like this out there between people from every side of the proverbial chasm. They don't take away the pain and fear, but they could serve as a step in the right direction.