More

Still know someone who’s against gay marriage? Show them this video, and watch them cry like a baby.

This video is almost too beautiful for words. But thank goodness for poetry.

09.25.14

It's super easy, no purchase or donation necessary, and you help our oceans! That's what we call a win-win-win. Enter here.

This Valentine’s Day, we're bringing back our favorite giveaway with Ocean Wise. You have the chance to win the ultimate ocean-friendly date. Our recommendation? Celebrate love for all your people this Valentine's Day! Treat your mom friends to a relaxing spa trip, take your best friend to an incredible concert, or enjoy a beach adventure with your sibling! Whether you're savoring a romantic seafood dinner or enjoying a movie night in, your next date could be on us!

Here’s how to enter:

She’s up before the sun and still going at bedtime. She’s the calendar keeper, the lunch packer, the one who remembers everything so no one else has to. Moms are always creating magic for us. This Valentine’s Day, we’re all in for her. Win an eco-friendly spa day near you, plus a stash of All In snack bars—because she deserves a treat that’s as real as she is. Good for her, kinder to the ocean. That’s the kind of love we can all get behind.

Special thanks to our friends at All In who are all in on helping moms!

Grab your favorite person and get some much-needed ocean time. Did you know research on “blue spaces” suggests that being near water is linked with better mental health and well-being, including feeling calmer and less stressed? We’ll treat you to a beach adventure like a surfing or sailing class, plus ocean-friendly bags from GOT Bag and blankets from Sand Cloud so your day by the water feels good for you and a little gentler on the ocean too.

Special thanks to our friends at GOT Bag. They make saving the ocean look stylish and fun!

Love nights in as much as you love a date night out? We’ve got you. Have friends over for a movie night or make it a cozy night in with your favorite person. You’ll get a Disney+ and Hulu subscription so you can watch Nat Geo ocean content, plus a curated list of ocean-friendly documentaries and a movie-night basket of snacks. Easy, comfy, and you’ll probably come out of it loving the ocean even more.

Soak up the sun and catch a full weekend of live music at BeachLife Festival in Redondo Beach, May 1–3, 2026, featuring Duran Duran, The Offspring, James Taylor and His All-Star Band, The Chainsmokers, My Morning Jacket, Slightly Stoopid, and Sheryl Crow. The perfect date to bring your favorite person on!

We also love that BeachLife puts real energy into protecting the coastline it’s built on by spotlighting ocean and beach-focused nonprofit partners and hosting community events like beach cleanups.

Date includes two (2) three-day GA tickets. Does not include accommodation, travel, or flights.

Stay in and cook something delicious with someone you love. We’ll hook you up with sustainable seafood ingredients and some additional goodies for a dinner for two, so you can eat well and feel good knowing your meal supports healthier oceans and more responsible fishing.

Giveaway ends 2/15/26 at 11:59pm PT. Winners will be selected at random and contacted via email from the Upworthy. No purchase necessary. Open to residents of the U.S. and specific Canadian provinces that have reached age of majority in their state/province/territory of residence at the time. Please see terms and conditions for specific instructions. Giveaway not affiliated with Instagram. More details at upworthy.com/oceandate

There's a reason Dr. Burstyn's "How to pick up a cat" video has been viewed 23 million times.

Handling a cat may seem like a delicate matter, but being delicate isn't actually the way to go.

If you've ever tried to make a cat do something it doesn't want to do, you've likely experienced the terror that a cat's wrath can invoke. Our cute, cuddly feline friends may be small, but the razor blades on their feet are no joke when they decide to utilize them. Even cats who love us can get spicy if we try to manhandle them, so we can imagine how things will go with cats who don't know us well. But sometimes it's necessary to handle a cat even if it's resistant to the idea.

This is where Vancouver veterinarian Dr. Uri Burstyn comes in. His "How to pick up a cat like a pro" video, in which he demonstrates a few ways of picking up and handling a cat, has been viewed over 23 million times since he shared it in 2019. Unlike many viral videos, it's not humorous and nothing outrageous happens, but the combo of Burstyn's calm demeanor and his repeated instructions to "squish that cat" has endeared him to the masses.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

The video truly is helpful; he shows the ways to pick up a cat that make them feel the most secure using his cats, one-year-old Claudia and 14-year-old Mr. Pirate. He explains that cats spook very easily and it's best to introduce yourself to them gently. Let them sniff your fingers, keeping your fingers curled in, and once they've sniffed you, you can often give them a light rub on the cheek or under the chin.

Picking them up is a different story. The reason many cats will claw or scratch you when you try to pick them up is because they feel unsupported or unsafe, so they'll scramble around trying to get some footing. Burstyn shows how he picks up Claudia with one hand under the chest and one hand under her abdomen. If he needs to carry her around, he squishes her into his body so she feels "nice and supported." He may even put a hand under her front paws.

Then came the best part of the video: "Squish That Cat"

"Now if we do have a cat who's trying to get away from us?" Burstyn said. "We always squish that cat. If you're trying to hold the cat down, whether it's to trim their nails or to give them a pill, or whether you just want to have a cat not run off for a moment, squish that cat. All you need to know about cat restraint is to squish that cat."

Burstyn explains that cats generally feel very secure being squished, even if they're really scared.

"Sometimes cats come to me in the clinic, and they're quite afraid," he said. "And you just gently squish them, and they'll sit there and kind of not hurt themselves, not hurt us. Just hang out and let us do our thing."

He demonstrated putting a towel over the cat, explaining, "If you have a towel handy, this is one of the best cat restraint tools around. You can just throw a towel on the catty and squish her with the towel, that way they won't get a claw into you if they are scrambling about a bit. Very safe and gentle, and generally cats are very, very happy to be squished like that."

Dr. Burstyn also showed how to do a "football hold," tucking the cat under your arm with them facing backwards. "So this is kind of an emergency way if you really need to carry a cat somewhere in a hurry," he said. Scooping up Claudia, he explained, "Little head's under your arm, butt in your hand, and you squish her tight to your body. And with that little football carry, you can basically hold a cat very securely and very safely, because it's really hard for them to rake you with their hind legs."

If you're worried about over-squishing your cat, Dr. Burnstyn says don't. "You don't have to worry about hurting a cat," he said. "They're very, very tough little beasts. You know, just squishing them against your body's never going to do them any harm. In fact, they tend to feel more safe and secure when they're being held tightly."

Dr. Burnstyn also demonstrated how to pick up and set down a "shoulder cat" who insists on climbing onto people's shoulders and hanging out there, as Mr. Pirate does. It's highly entertaining, as Mr. Pirate is a big ol' chonky kitty.

@yozron Visit TikTok to discover videos!

People in the comments loved Dr. Burnstyn's demonstration, with several dubbing him the Bob Ross of veterinary medicine. Even people who don't have cats said they watched the whole video, and many loved Claudia and Mr. Pirate as well.

"This is just proof that cats are liquid."

"12/10 cat. Excellent squishability."

"So essentially, cats love hugs? That's the most wonderful thing i've heard all day."

"This cat is so well mannered and looks educated."

"Mr Pirate is an absolute unit."

"S q u i s h . T h a t . C a t ."

"I need 'Squish that cat' shirt.

"Dang, that actually helped with my female cat. She has been through at least two owners before me and had some bad expriences which obviously resulted in trust issues. She has now been with me for two years and it had gotten loads better, but she still did not want me to hold her. Normally I simply would have let her be, but for vet visits and such it was not an ideal situation. But then I saw this video and tried to squish the cat. And she loves it! She is turning into quite the snuggly bug. Thank you!"

So there you go. When all else fails, squish that cat and see what happens.

You can follow Dr. Burstyn on YouTube at Helpful Vancouver Vet.

"I had no idea that anything like this could ever be part of my life."

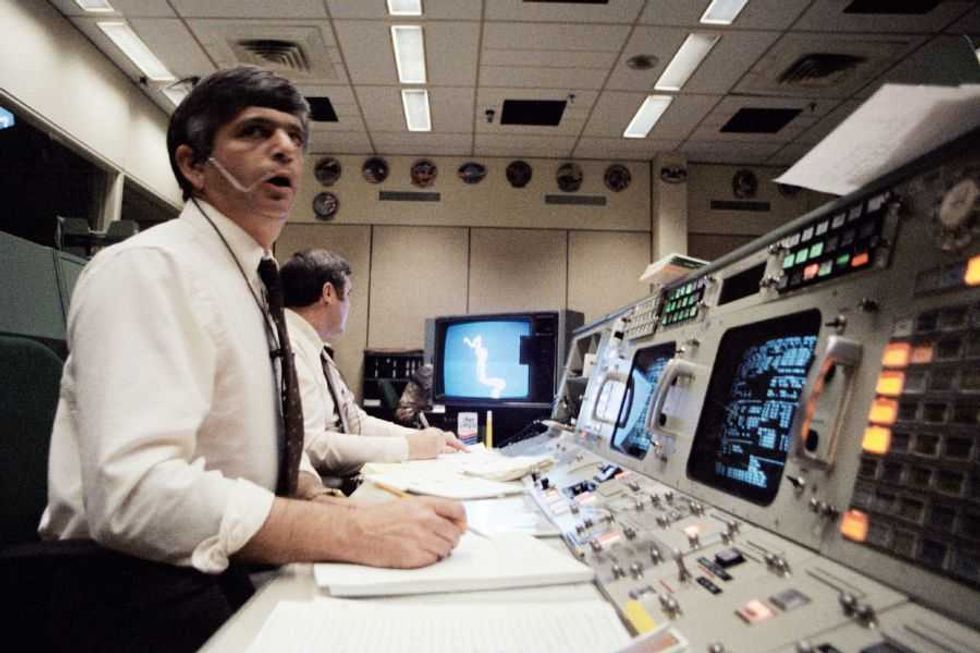

The Challenger crew.

In January 1986, the space shuttle Challenger took off with seven crew members on board, ready to make history. It was a big deal because this space mission wasn't just full of astronauts. Christa McAuliffe, a high school history teacher, was on board the spacecraft after winning a contest for the Teacher in Space Project. This would've made her the first teacher in space, so schools across the country wheeled televisions into their classrooms to allow students to watch history.

Instead, tragedy struck. The shuttle exploded just 73 seconds after takeoff due to "the destruction of the seals that are intended to prevent hot gases from leaking through the joint during the propellant burn of the rocket motor," according to NASA. All seven passengers on the Challenger perished in the explosion, leaving the country in shock.

January 2026 was the 40th anniversary of the accident, and NewsChannel 5 caught up with one of the teachers who was competing for the seat McAuliffe occupied. Carolyn Dobbins taught at McMurray Middle in Tennessee in 1984 when NASA announced the Teacher in Space Project. Having always wanted to go to space, Dobbins applied for a seat on the shuttle. Over 11,000 teachers applied to be the one who would make history, and to Dobbins' surprise, she was chosen as a semifinalist. "I had no idea that anything like this could ever be part of my life," she said.

The retired teacher explains to the news station that she spent days on her application for space, saying, "An amazing thing happened." She shares about the series of snow days in 1985. "Snow day. Then we had another snow day and another snow day. Those snow days were what I needed! It was basically a mini-book about your beliefs, your desire to go into space, getting to the soul of the person."

She admits that some of her students were worried about her going into space if she were to be chosen, but she brushed off their concerns, saying, "'Oh, I'll be back.'" Dobbins was completely confident in the success of the mission and excited to be able to do something she once thought was impossible. After being interviewed by a panel in Washington, D.C., she was sure she would be chosen for the mission. All of the teachers invited to be interviewed were also confident they'd be chosen, according to Dobbins. But only one could go, and the person chosen was 37-year-old mom of two, Christa McAuliffe, a teacher at Concord High School in Concord, New Hampshire.

Dobbins stood in front of her television watching the shuttle take off instead of experiencing it herself. Once the announcer said the magic words, "We have liftoff," the almost astronaut shares that she let out a sigh of relief before saying, "Way to go, Christa." She then turned off the television.

"Within seconds, the phone rang," Dobbins tells NewsChannel 5. "It was a friend. I said, 'Isn't it great? The shuttle has gone!' She said, 'Carolyn, you don't know.' It was the tone. You don't know. I just put the phone down, flipped on the TV. There it was. Already the footage was going of the explosion. That is still such an emotional moment."

Dobbins taught for 53 years before retiring, and while she would've been willing to go on another mission that aimed to put a teacher in space, she's thankful for the life she has been able to live.

Learning a new skill? Here's how to quickly level-up.

A woman learning how to play guitar.

Learning a new skill, such as playing an instrument, gardening, or picking up a new language, takes a lot of time and practice, whether that means scale training, learning about native plants, or using flashcards to memorize new words. To improve through practice, you have to perform the task repeatedly and receive feedback so you know whether you’re doing it correctly. Is my pitch correct? Did my geraniums bloom? Is my pronunciation understandable?

However, a new study by researchers at the Institute of Neuroscience at the University of Oregon shows that you can speed up these processes by adding a third element to practice and feedback: passive exposure. The good news is that passive exposure requires minimal effort and is enjoyable.

"Active learning of a... task requires both expending effort to perform the task and having access to feedback about task performance," the study authors explained. "Passive exposure to sensory stimuli, on the other hand, is relatively effortless and does not require feedback about performance."

So, if you’re learning to play the blues on guitar, listen to plenty of Howlin’ Wolf or Robert Johnson throughout the day. If you’re learning to cook, keep the Food Network on TV in the background to absorb some great culinary advice. Learning to garden? Take the time to notice the flora and fauna in your neighborhood or make frequent trips to your local botanical garden.

If you’re learning a new language, watch plenty of TV and films in the language you are learning. The scientists add that auditory learning is especially helpful, so listen to plenty of audiobooks or podcasts on the subject you’re learning about.

But, of course, you also have to be actively learning the skill as well by practicing your guitar for the recommended hours each day or by taking a class in languages. Passive exposure won't do the work for you, but it's a fantastic way to pick up things more quickly. Further, passive exposure keeps the new skill you're learning top-of-mind, so you're probably more likely to actively practice it.

Researchers discovered the tremendous benefits of passive exposure after studying a group of mice. They trained them to find water by using various sounds to give positive or negative feedback, like playing a game of “hot or cold.” Some mice were passively exposed to these sounds when they weren't looking for water. Those who received this additional passive exposure and those who received active training learned to find the water reward more quickly.

“Our results suggest that, in mice and in humans, a given performance threshold can be achieved with relatively less effort by combining low-effort passive exposure with active training,” James Murray, a neuroscientist who led the study, told University of Oregon News. “This insight could be helpful for humans learning an instrument or a second language, though more work will be needed to better understand how this applies to more complex tasks and how to optimize training schedules that combine passive exposure with active training.”

The one drawback to this study was that it was conducted on mice, not humans. However, recent studies on humans have found similar results, such as in sports. If you visualize yourself excelling at the sport or mentally rehearse a practice routine, it can positively affect your actual performance. Showing, once again, that when it comes to picking up a new skill, exposure is key.

The great news about the story is that, in addition to giving people a new way to approach learning, it’s an excuse for us to enjoy the things we love even more. If you enjoy listening to blues music so much that you decided to learn for yourself, it’s another reason to make it an even more significant part of your life.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

This article originally appeared last year.

Most people never regret just staying silent.

A woman with her finger over her mouth.

It can be hard to stay quiet when you feel like you just have to speak your mind. But sometimes it's not a great idea to share your opinions on current events with your dad or tell your boss where they're wrong in a meeting. And having a bit of self-control during a fight with your spouse is a good way to avoid apologizing the next morning.

Further, when we fight the urge to talk when it's not necessary, we become better listeners and give others a moment in the spotlight to share their views. Building that small mental muscle to respond to events rather than react can make all the difference in social situations.

One way people have honed the skill of holding back when they feel the burning urge to speak up is the WAIT method, an acronym for the question you should ask yourself in that moment: "Why Am I Talking?" Pausing to consider the question before you open your mouth can shift your focus from "being heard" to "adding value" to any conversation.

The Center for The Empowerment Dynamic has some questions we should consider after taking a WAIT moment:

The WAIT method is a good way to avoid talking too much. In work meetings, people who overtalk risk losing everyone's attention and diluting their point to the extent that others aren't quite sure what they were trying to say. Even worse, they can come across as attention hogs or know-it-alls. Often, the people who get to the heart of the matter succinctly are the ones who are noticed and respected.

Just because you're commanding the attention of the room doesn't mean you're doing yourself any favors or helping other people in the conversation.

The WAIT method is also a great way to give yourself a breather and let things sit for a moment during a heated, emotional discussion. It gives you a chance to cool down and rethink your goals for the conversation. It can also help you avoid saying something you regret.

So if it's a work situation, like a team meeting, you don't want to be completely silent. How often should you speak up?

Cary Pfeffer, a speaking coach and media trainer, shared an example of the appropriate amount of time to talk in a meeting with six people:

"I would suggest a good measure would be three contributions over an hour-long meeting from each non-leader participant. If anyone is talking five/six/seven times you are over-participating! Allow someone else to weigh in, even if that means an occasional awkward silence. Anything less seems like your voice is just not being represented, and anything over three contributions is too much."

Ultimately, the WAIT method is about taking a second to make sure you're not just talking to hear yourself speak. It helps ensure that you have a clear goal for participating in the conversation and that you're adding value for others. Knowing when and why to say something is the best way to make a positive contribution and avoid shooting yourself in the foot.

"Children in the '90s played games that forced the brain to fail and try again."

Kids playing video games.

There was nothing more frustrating as a kid in the '90s than almost completing a level in a game only to hear that dreaded sound. It was your last life blinking before your eyes. Your only choice was to start over or turn off the video game and try again tomorrow. There was no getting around the fact that you were going to have to do it all over again, but next time you'd be faster, smarter, and better prepared than the last.

This is a skill that was built through repetition for Millennials and Gen X. That small annoyance in older video games exercised a muscle that would be helpful throughout life—one that increased the cognitive skills of these two older generations. And while older Gen Zers experienced this important brain development tool built into older video games, younger Gen Zers and Gen Alpha are critically missing out.

The brain development skills consistently present in video games from the late '70s through the '90s were frustration tolerance, critical thinking skills, delayed gratification, and pattern recognition. Licensed mental health counselor and former teacher, Veronica Lichtenstein, discussed '90s video games with Newsweek, saying, "You fought through levels, memorized patterns and finally saw the ending. It felt like you accomplished something. Your brain gave you this solid, lasting dose of satisfaction, like finishing a tough project.”

In a video by The Pizza Breakroom on Instagram, two men discuss an article allegedly written by a psychologist exploring this very phenomenon. "He said children in the '90s played games that forced the brain to fail and try again," one man reads. "Mario, Sonic, Prince of Persia, you had three lives, no saves, no hints. When you lost you learned patience, planning, and frustration tolerance. Today, many games guide kids step-by-step. Autosave every ten seconds and removes real challenge."

Games like Roblox and Minecraft, which a lot of kids enjoy playing, are never-ending. The game seems to be designed to encourage the player to spend money to keep up with trends, such as offering new "skins." This isn't game money; it's actual money that requires an adult's debit or credit card. There are no significant rewards offered through the satisfaction of beating a level or the game in its entirety. If a child is struggling in the room they chose to play in, the game allows them to leave and enter a different room filled with different players.

“Nineties games are a challenge for building your skills. Today’s games are often a test for your psychological resistance. A great deal are built to track, exploit and addict,” Lichtenstein shares with Newsweek.

But all hope is not lost on building these important skills in the youngest generations. Nineties games are still around, along with their original, refurbished consoles. There are also all-in-one Nintendo and Sega consoles that have all the '90s games preloaded. Parents can encourage video game play on actual consoles, not tablets or computers. A big perk is also that parents can actually get to play with their child while jogging their own memory of cheat codes and game layout.

For some, it may be difficult to watch their child struggle to figure out how to move through the old school games, but the point is for them to learn frustration tolerance and other cognitive skills. These skills are essential to navigate the world as an adult, and introducing kids to the games their parents played at their age is a fun way to do it.