It’s one thing for a president to shorten someone’s prison sentence. It’s another thing entirely to take them out to lunch.

On March 30, 2016, President Obama granted early prison releases to 61 individuals who were serving time for nonviolent drug-related crimes. Over the course of his presidency, he’s issued 248 such commutations (sentence reductions) — more than the previous six presidents combined, according to the White House.

But this time, he decided to surprise a group of formerly incarcerated individuals — some of whom had just been released from prison that day, others who had been released in years prior under Presidents Clinton and Bush — at a White House meet-and-greet. “Turns out I’ve got an opening in my schedule,” he told them. “So let’s have some lunch.”

The president took the group to a nearby restaurant, where he gave them each a chance to share their stories and talk about how to fix the U.S. criminal justice system so that more people like them don’t end up spending their entire lives behind bars.

President Obama leads the group to lunch at Busboys and Poets in Washington, D.C. Photo by Kevin Dietsch-Pool/Getty Images.

Phillip Emmert, for example, was sentenced to 27 years in prison for methamphetamine charges.

Meth is a major problem in rural Arkansas, where Emmert grew up. His original sentence came with no opportunity for parole, even though it was his first offense and a nonviolent one.

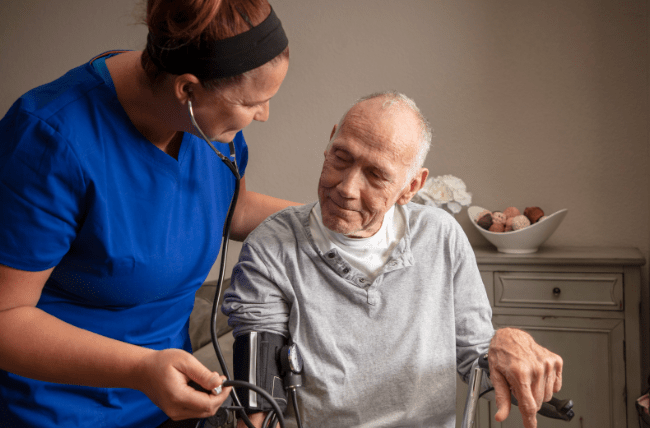

He was granted clemency by President Bush in 2006 after serving 14 years. He found work as a housekeeper at the Iowa City VA soon after. But that’s not so common — less than half of ex-convicts find employment in their first year after release, and there are nearly 800 occupations that ban the hire of applicants with criminal records.

President Obama and Phillip Emmert. Photo by Nicholas Kamm/Stringer/Getty Images.

Then there’s Ramona Brant, who was sentenced to life for conspiracy to sell cocaine.

Her boyfriend was also charged. She confesses that she was aware he was selling drugs, but she denies any active involvement. Like Emmert, this was a nonviolent crime and her first offense.

But a 1984 law laid down strict per-kilo punishments for drug dealers, so the specifics of her case were irrelevant in the eyes of the law.

Brant is also black, and according to the NAACP, African-Americans are 10 times more likely to be imprisoned for drugs, even though white Americans use drugs at a rate five times higher.

After 21 years in jail, Brant had her life sentence commuted by Obama in 2015. She walked free on Feb. 1, 2016.

Ramona Brant and President Obama. Photo by Kevin Dietsch-Pool/Getty Images.

Serena Nunn was 19 when she, too, was sentenced to 15 years for conspiracy to distribute cocaine.

Like Brant, she says knew what her boyfriend was up to when she dropped him off at meets. But she says her involvement stopped there. Yet, thanks to mandatory minimum sentencing laws, she faced more than 15 years behind bars while the drug ring leader — who had prior drug, rape, and manslaughter convictions — got away with only seven years because of a deal with the prosecution.

In 1999, Nunn became the first woman at her federal prison to earn a community college degree. One year later, President Clinton commuted her sentence. And as of 2012, she’s a licensed attorney in Georgia.

Serena Nunn (far left) at lunch with the president. Photo by Nicholas Kamm/Stringer/Getty Images.

Finally, meet Norman Brown. He was sentenced to life for selling crack cocaine.

Brown did have two prior counts against him for minor offenses, which certainly didn’t help the harsh sentencing. But neither did the fact that federal mandatory minimum sentencing laws set in place in the 1980s punished crack cocaine dealers at a rate 100 times harsher than powdered cocaine dealers — despite the fact that crack is just a different form of the same drug. Put another way, the punishment for 5 grams of crack was equal to the punishment for 500 grams of powder cocaine.

And, of course, more than 80% of the prisoners serving time for crack are black, like Norman Brown.

The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 reduced this ratio to 18-to-1, and Brown was given clemency by President Obama in 2015 after serving 24 years in prison. He’s committed himself to working with underprivileged youth in his community to help them avoid the same mistakes he made.

Norman Brown (front right). Photo by Kevin Dietsch-Pool/Getty Images.

“They’re Americans who’d been serving time on the kind of outdated sentences that are clogging up our jails and burning through our tax dollars,” President Obama said on Facebook. “Simply put, their punishments didn’t fit the crime.”

In a letter that he sent to each of the ex-convicts who received commutations that day, the president added:

“I am granting your application because you have demonstrated the potential to turn your life around. Now it is up to you to make the most of this opportunity. It will not be easy, and you will confront many who doubt people with criminal records can change. Perhaps even you are unsure of how you will adjust to your new circumstances. But remember that you have the capacity to make good choices. By doing so, you will affect not only your own life, but those close to you. You will also influence, through your example, the possibility that others in your circumstances get their own second chance in the future.”

President Obama is right: Everyone deserves a second chance. But his lunch dates also brought up a huge, systemic problem.

When I started reading about each of these cases, I was appalled by the trends that emerged. The fact that a one-time drug infraction can destroy someone’s life is hard to believe; the fact there are a hundred thousand more stories just like these is equally as depressing.

Consider this: Before mandatory sentencing laws were enacted in 1980, there were about 24,600 incarcerated U.S. citizens. By 2013, that number was nearly nine times higher — and half of those charges are drug-related.

It’s like we’re spending all of our time and money trying to catch the water leaking from the pipes instead of fixing the leak. Yes, drug use can destroy lives. But so can an obscenely harsh prison sentence. And neither one actually solves the poverty, mental health struggles, addiction, and general sense of desperation that leads to heavy drug use in the first place.

While there are still a lot of problems with the American justice system, it’s a step in the right direction that our president is listening to the people most affected by these federal laws. But I hope Obama is listening closely — because we have a long way to go.