There's been a quiet protest happening in the trees of Appalachia. Now, it's catching on.

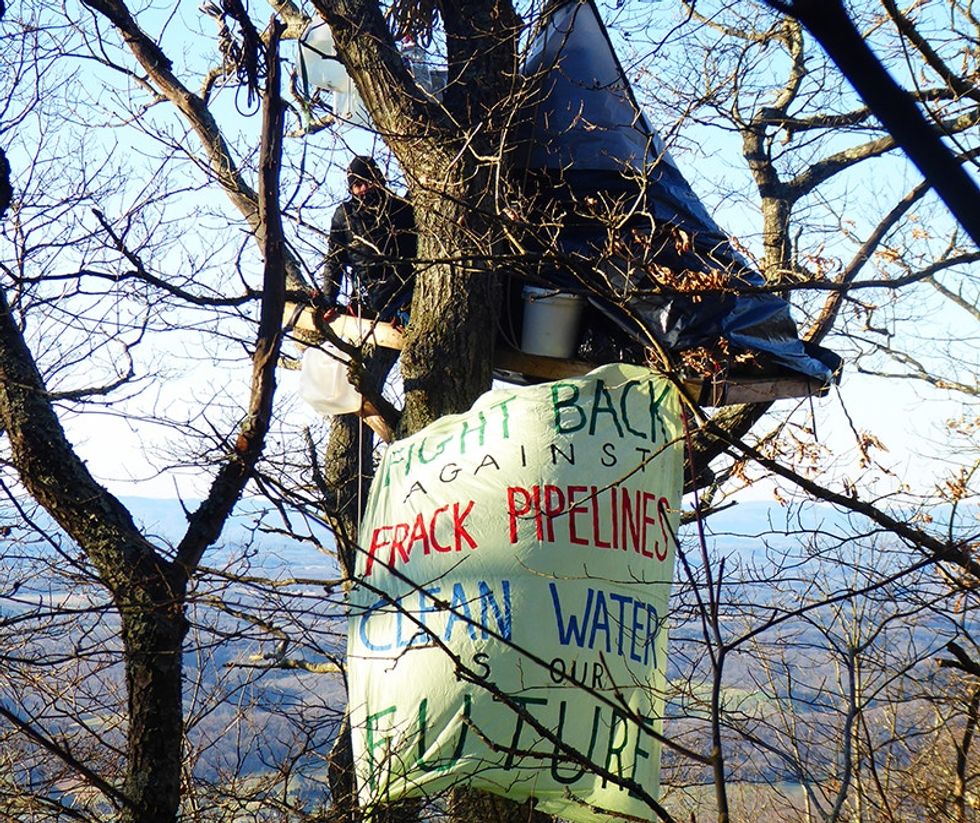

When Abigail peeks out from her perch — a wooden platform dangling high in a tree on a mountain ridge in West Virginia — she sees a nearly picture-perfect landscape.

She points out roaming farm animals and watches cars drive the few country roads that border the Jefferson National Forest. "The sunsets are incredible," Abigail describes. "And it’s pretty peaceful when the winds aren’t too strong."

The 22-year-old Virginian (who asked us not to disclose her last name because of the risk involved in her protest) has called this sweeping landscape around Peters Mountain — and this one tree — home since she and others climbed up its branches on a mission on Feb. 26, 2018.

She chose the tree she’s in for a reason: It sits right where the Mountain Valley Pipeline is slated to carry natural gas through the fragile limestone terrain beneath its roots.

The construction of this pipeline would mean the destruction of this landscape, and Abigail is determined to stall that as long as possible.

The Mountain Valley Pipeline was first proposed in 2014 and has been met with community resistance every step of the way.

The route moves from north of Clarksburg, West Virginia, down to just southeast of Roanoke, Virginia — where it's been proposed it will continue another 70 miles south into North Carolina. The 42-inch-diameter pipeline will carry fracked natural gas, and residents like Becky Crabtree — who lives along the route and whose sheep Abigail can see from her tree — fear for their health, communities, and land.

Pipeline route map created by Upworthy.

"We can’t find record of a pipeline of this size ever being built on such a steep grade," Crabtree says. "There are so many questions we have, and no one is answering any of them for us."

Crabtree's property at the base of Peters Mountain is intersected by the pipeline, and her concerns about it are endless. She worries about sinkholes, about the quality of water reservoirs in the area, and about the construction traffic planned on her little one-lane road. She worries about the fence around her sheep field that she’ll have to pay to rebuild once MVP widens that road for their use. She worries about the effect the pipeline will have on the Appalachian Trail, which it will cross under just a couple hundred feet from Abigail’s tree.

Armed with many of the same concerns as Crabtree, over 400 landowners along the pipeline’s route refused to grant MVP easements on their property. These landowners were sued by MVP in 2017 for access to the land; eventually, a federal court will grant the private company access by condemning each person’s land through eminent domain, claiming that the pipeline serves a public good.

Upworthy reached out to MVP for a comment, but has not heard back.

Just a few dozen miles from Abigail, a 60-year-old woman nicknamed "Red" has also taken to the trees to stop pipeline construction on her family’s Virginia land.

"When I saw the tree sits on Peters Mountain," Red Terry says, "I knew what we had to do." Her husband’s family has lived on the Roanoke County land for generations, preserving the streams, wetlands, and an historic orchard that the pipeline will run right through.

"Everyone wants MVP’s money," she quips. "But there are some things in life worth a hell of a lot more than money."

Red's tree-sit, like Abigail's, has been surrounded by tree-felling in recent weeks. But the presence of the tree-sitters — along with dozens of supporters on the ground — has prevented MVP from cutting many trees in the pipeline's path. Although the community supporting these protests is vast, the threat of legal consequences has kept many, like Abigail, from disclosing personal information.

As construction ramps up, Red and Abigail aren’t the only ones taking direct action.

In Giles County, Virginia, a blockade was erected by pipeline opponents on an MVP access road. A single protester has been perched atop a 50-foot log placed vertically in the road for three weeks and counting, effectively halting construction of both the access road and the pipeline. She has not come down once, despite the continued presence of law enforcement preventing supporters from replenishing her supply of food and water. The banner hanging with her aptly reads: "The fire is catching: No pipelines."

Back in West Virginia, Crabtree says she was "jumping up and down delighted" to learn about the folks who climbed into the trees on Peters Mountain.

"We hadn’t noticed them until we read about them," she says. "But the more people that learn about them, the more admiration there is in the community. The more sense there is that we support people that ‘lay it down’ for our environment. That takes courage and wherewithal. It takes some extra teeth."

Local supporters have been so grateful for the tree-sitters that just a couple weeks ago, they held a spaghetti dinner fundraiser in support.

That evening, dozens of folks gathered in a church basement to eat, talk with friends and neighbors, and contribute to the cause on Peters Mountain. Crabtree’s granddaughters ran a table complete with markers and construction paper where well-wishers could write thank-you notes to be delivered up the ridge.

Up in her oak tree, Abigail recounts tales of the past three years, which she has spent opposing this pipeline.

“It got to the point where we had tried all these options to fight this,” she reports. “We talked to our representatives. We tried running our own candidates. We wrote letters to the editor. We had people sign petitions. Didn’t work, didn’t work, didn’t work. This is the only thing I feel like I have left.”

This fight comes at a time of widespread and increasing resistance to pipelines and other destructive fossil fuel projects around the country and the world.

Just east of the MVP route, folks are fighting the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a natural gas pipeline that — among a multitude of other issues — has a compressor station planned for Union Hill, Virginia, a community built by the descendants of freed slaves.

Down in Louisiana, the Bayou Bridge Pipeline is scheduled to cross 700 bodies of water, including a reservoir that supplies drinking water to the United Houma Nation and 300,000 Louisiana residents. This is the tail end of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which thousands protested last year at Standing Rock.

The list goes on: Mariner East 2, Rover, Line 3, Trans Mountain. But so do the stories of people rising up in the face of this ongoing destruction of land and communities.

"I don’t have a lot to lose being in this tree," Abigail shares, as she settles into her sleeping bag for another night on the mountain. "But as a young person and person from this region, I do have a lot to lose with this pipeline."

For updates from resistance to the Mountain Valley Pipeline, follow Appalachians Against Pipelines and Farmlands Fighting Pipelines on Facebook. To learn about some of the other pipeline fights mentioned here, follow No Bayou Bridge, Makwa Initiative, and Camp White Pine.

A Generation Jones teenager poses in her room.Image via Wikmedia Commons

A Generation Jones teenager poses in her room.Image via Wikmedia Commons

A van travels down the road.

A van travels down the road.  A person plays the guitar.

A person plays the guitar.  A man smiles.

A man smiles.  A damaged vehicle sits on the side of a road.

A damaged vehicle sits on the side of a road.