One moment in history shot Tracy Chapman to music stardom. Watch it now.

She captivated millions with nothing but her guitar and an iconic voice.

Imagine being in the crowd and hearing "Fast Car" for the first time

While a catchy hook might make a song go viral, very few songs create such a unifying impact that they achieve timeless resonance. Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car” is one of those songs.

So much courage and raw honesty is packed into the lyrics, only to be elevated by Chapman’s signature androgynously soulful voice. Imagine being in the crowd and seeing her as a relatively unknown talent and hearing that song for the first time. Would you instantly recognize that you were witnessing a pivotal moment in musical history?

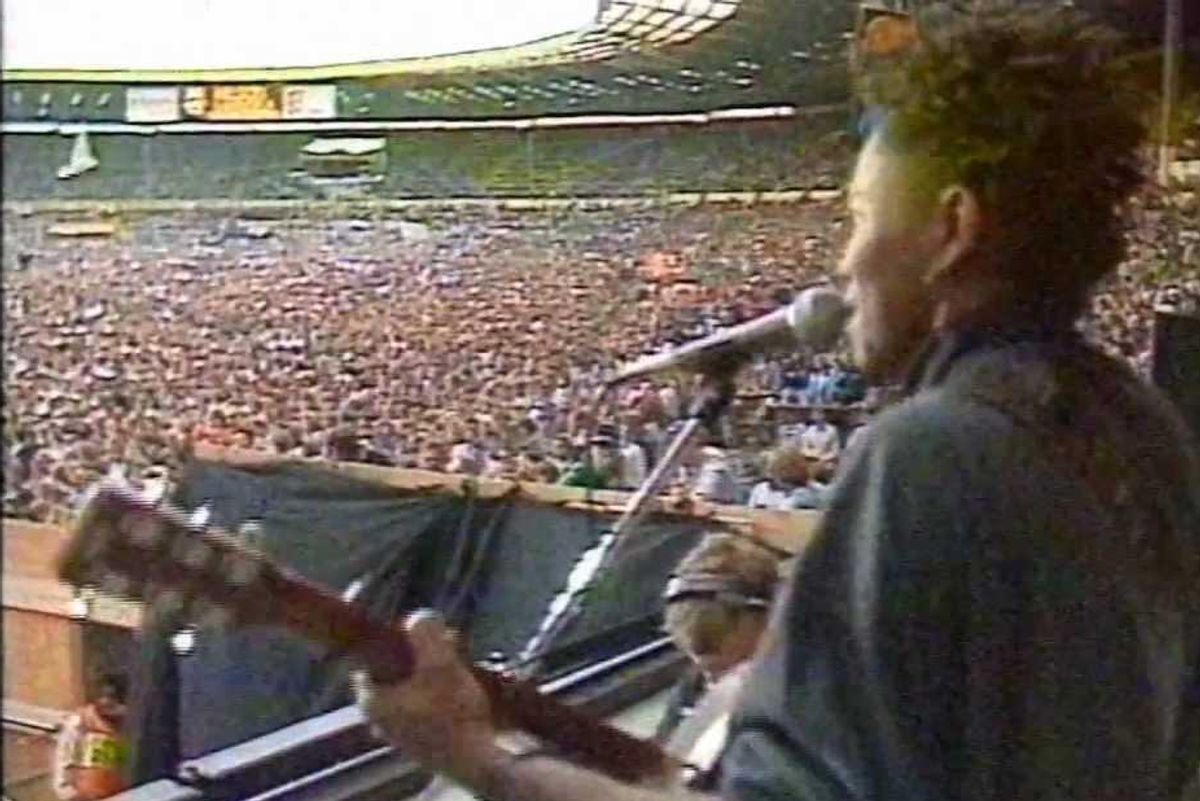

For concert goers at Wembley Stadium in the late 80s, this was the scenario.

The year was 1988. Seventy-two thousand people gathered—along with 600 million more watching along on their televisions—to see headliner Stevie Wonder as part of Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday tribute concert.

However, technical difficulties (or perhaps some divine timing) rendered Wonder unable to perform his act. Chapman had already played a three-song set earlier in the afternoon, and yet she agreed to step up to the microphone.

Armed with nothing but her guitar, the shy and stoic Chapman captivated everyone to silence. And the rest is history.

Watch:

Using just a simple story, “Fast Car” conveyed a million different themes—the challenges of class and poverty, seeking escape from a small town and yearning for freedom and new opportunity. It’s easy to see why some find the song heartbreaking, while others find it hopeful.

After the Mandela gig, the song became a worldwide hit, earning Chapman Grammy awards and shooting her to stardom. What’s more, she introduced a new wave of socially-conscious music filled with gentle yet brutally truthful introspection. Since that fateful day, her name is forever synonymous with a quiet revolution. We are quite lucky to get to experience it so many years later.

At the 2024 Grammys, Tracy Chapman took the stage again after 15 years out of the public eye for a surprise performance of "Fast Car" alongside country music star Luke Combs. After the performance, "Fast Car" entered the Top 40 and climbed country radio charts.

This article originally appeared two years ago.

- Queen releases a never heard ballad sung by Freddie Mercury and it has fans in tears ›

- The one must-see video from Disney Plus' Beatles documentary ›

- Watch a young and fabulous Elton John play 'Tiny Dancer' for the very first time ›

- Tracy Chapman praises Luke Combs country cover of 'Fast Car' - Upworthy ›

- Tracy Chapman sang 'Fast Car' with Luke Combs at the Grammys - Upworthy ›

- How a music festival raised millions for the unhoused - Upworthy ›

- Stevie Wonder mesmerizes 1972 audience with the first talkbox performance - Upworthy ›