For most of us, sweet potatoes can be two things: a dessert or a side. For some kids, though, they could be a lifeline.

We all know that hunger is a big problem in Africa. Some sources say over 200 million people there are hungry or undernourished.

But often the answer isn’t just getting food to those in need — it’s getting them the right kinds of food.

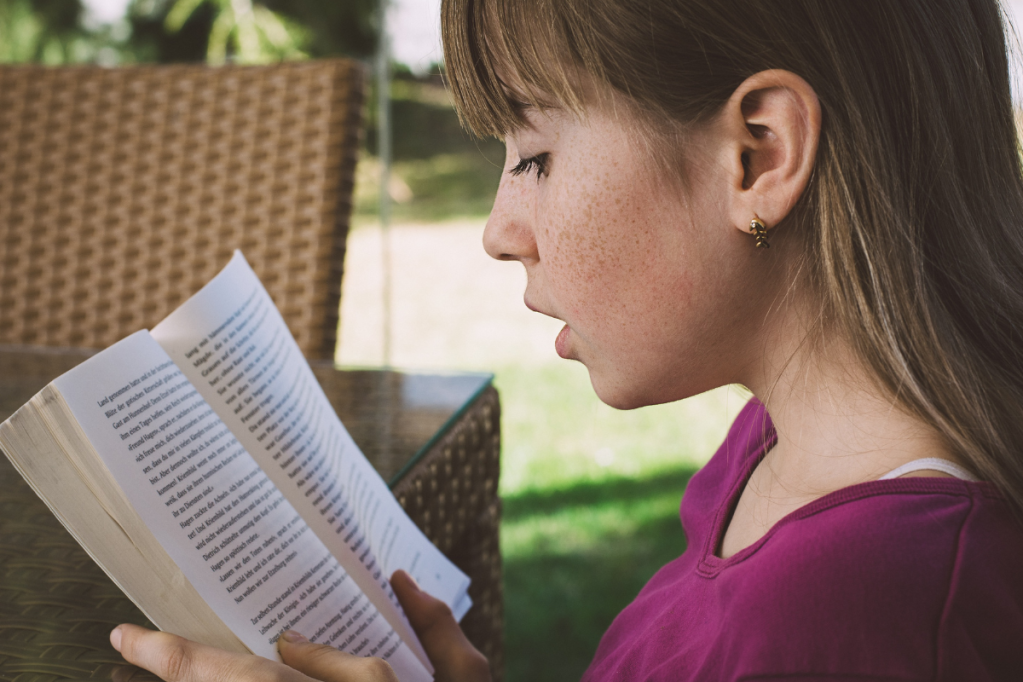

Lots of rice, beans, and corn. Not a lot of nutrients. Photo by Simon Maina/AFP/Getty Images.

Jane Howard of the World Food Programme told the BBC, “There are certainly extreme circumstances where children starve to death. … But the truth is that the vast majority of those numbers that we’re talking about are children who, because they haven’t had the right nutrition in the very earliest parts of their lives, are really very susceptible to infectious diseases.”

That’s where the sweet potato comes in.

Poor families in Africa often have access to cheap crops, but they lack important micronutrients like Vitamin A.

In sub-Saharan African countries like Uganda and Ethiopia, it’s not too hard to get foods like rice and corn. And while those crops might be good for a full belly, they’re far too light on critical micronutrients.

That’s why about 250 million preschool-age children suffer from a Vitamin A deficiency, many of them in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Vitamin A deficiency, or VAD, sounds pretty tame compared to AIDS or malaria, but don’t let the name fool you. It can cause growth issues in kids, decreased immunity to infections, and even blindness, which, in children, often results in death.

With a little help from science, the sweet potato is becoming an unlikely hero in the fight against Vitamin A deficiency.

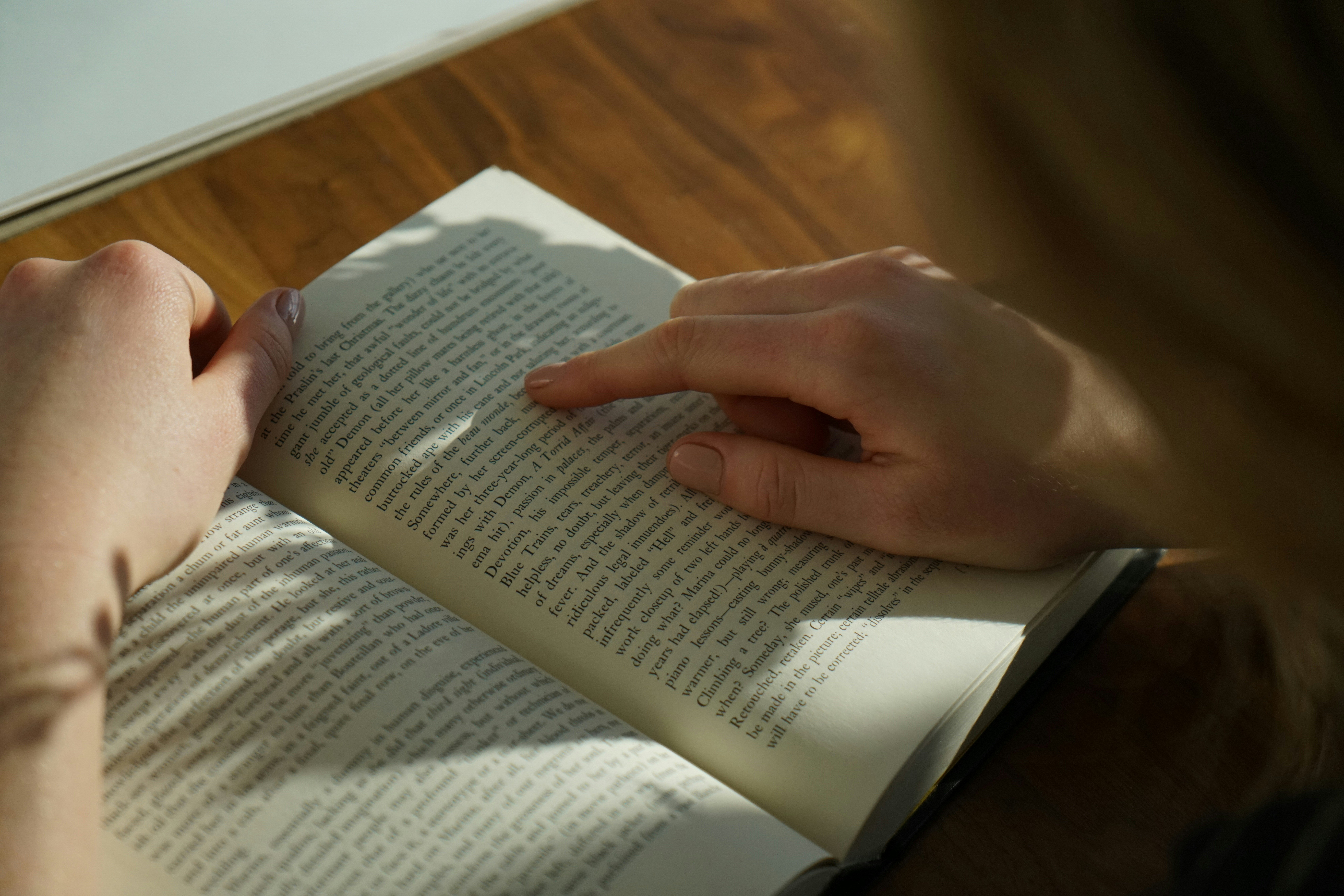

They don’t look like much, but they hold a ton of potential. Photo by Wally Hartshorn/Flickr.

Many years ago, researchers with the United Nations found that if they could give kids in Africa a Vitamin A capsule even just once every six months, they could cut the mortality rate for those kids by 25%. That’s huge.

But it would be even bigger if they could find a way to give Africans in poverty a sustainable, inexpensive source of Vitamin A year round that they could grow and trade themselves.

That’s where the idea of tackling the problem with “biofortification” came from — taking those cheap local crops and selectively breeding them to carry more nutrients.

Some of the most exciting progress so far comes in the form of … that’s right … the sweet potato. Best known for being the only food that can be eaten as both a pie and a fry, the orange sweet potatoes we enjoy here in the U.S. are already high in beta carotene (which our body turns into Vitamin A). The ones that grow in Africa, while popular and allegedly delicious, aren’t.

Until now.

Scientists have been homing in on the perfect breed of sweet potato: great flavor, easy growing, and plenty of Vitamin A.

Sweet potatoes can be turned into all kinds of yummy, Vitamin-A rich dishes. Photo by Avital Pinnick/Flickr.

Recently, Sunette Laurie, a senior researcher with the Agricultural Research Council, published a study detailing her team’s efforts to create the perfect sweet potato.

Step one is ratcheting up the beta carotene levels. But to have the kind of impact they’re imagining, Laurie’s team needs a strain of sweet potato that’s really easy to plant and grow and has a texture and flavor that Africans really dig.

She thinks they’ve got a couple of promising options, both with exotic-sounding names like “Impilo” and “Purple Sunset,” and now she’s working with local officials to get these fortified sweet potatoes in the hands of the community so they can start saving lives, whether the potatoes be casseroled, muffined, or simply steamed to taste.

Save room on that plate, though, for some Golden Rice, some Miraculous Maize, and a Super Banana.

While Laurie’s team is hard at work building a better sweet potato, other research teams around the world are tinkering with the rest of Africa’s local, nutrient-deficient crops.

The Golden Rice Project just got an award from the White House for its biofortified rice, while a team at the Queensland University of Technology is trying out genetically enhanced bananas in Uganda with the hopes of spreading them across the continent soon. There’s even special “orange maize” being grown in Zambia with supercharged levels of Vitamin A.

The more options malnourished kids all over the world have for getting access to nutrients, the better. What’s especially cool about these biofortified crops is that, in time, they’ll become a natural part of the local food trade and easily available to nearly everyone.

Maybe then we can “mash” VAD into obscurity, for good.

Correction: This article originally stated that the sweet potatoes are genetically engineered. They’re not. They are conventionally bred by selective breeding of crops. Thanks to Vidushi Sinha at HarvestPlus for the correction.