I work with a group of men who aren’t used to seeing themselves in the narrative unless they’re portrayed as villains.

These men are prisoners. They understand that much of America thinks they’re monsters who deserve to be locked in cages. They are the bastard, orphan sons of … every kind of woman you can imagine. They are also beloved sons and husbands and part of close families who come to visit them every week.

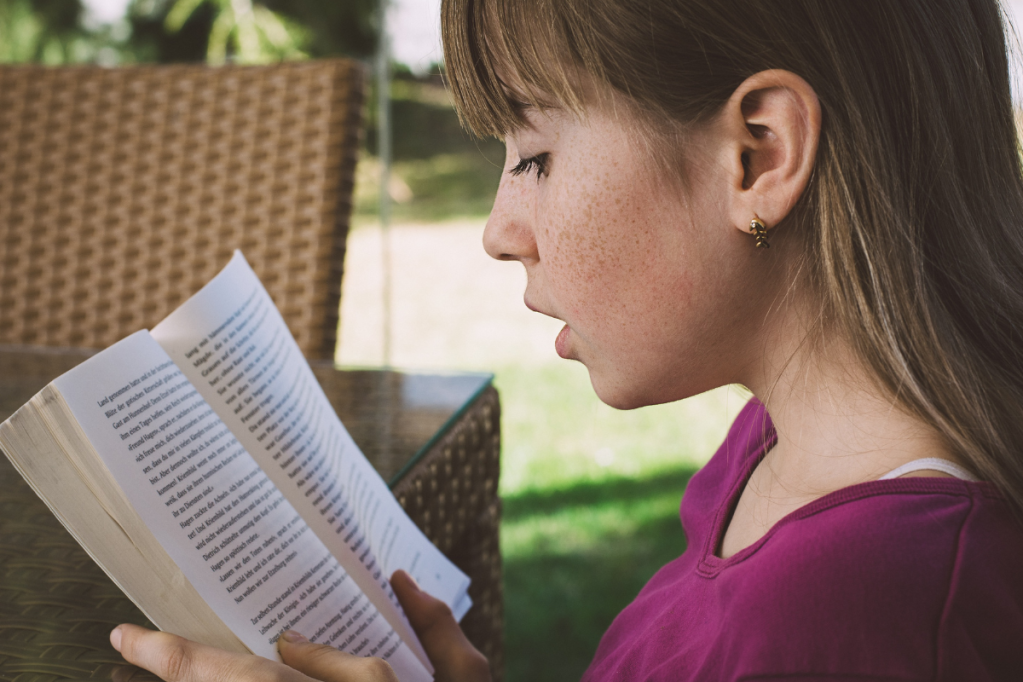

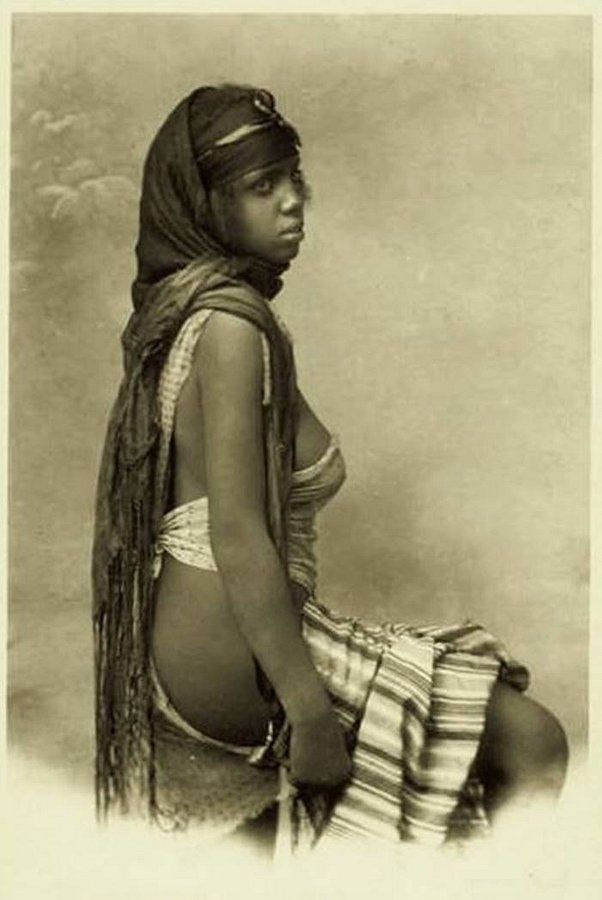

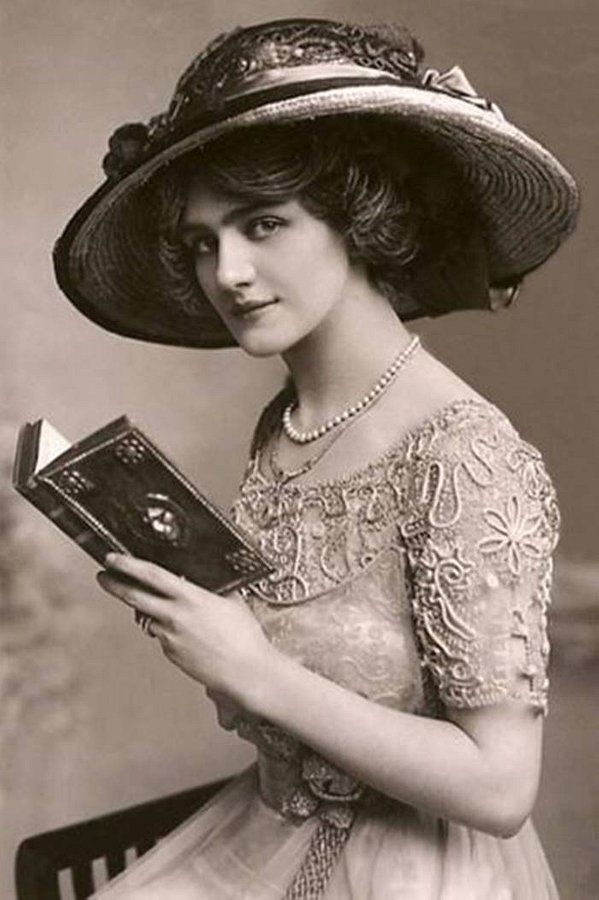

Photo by the author, used with permission.

Maybe they understand Alexander’s words in the musical, “Hamilton”: “Livin’ without a family since I was a child. My father left, my mother died, I grew up buckwild.” Many of them know all about living impoverished, in squalor, and about fathers who split. A few of them are in college, working on being scholars.

People look at them like they’re stupid. They’re not stupid.

Because our criminal justice system silences these men, I will be so bold as to tell (a little piece of) their story.

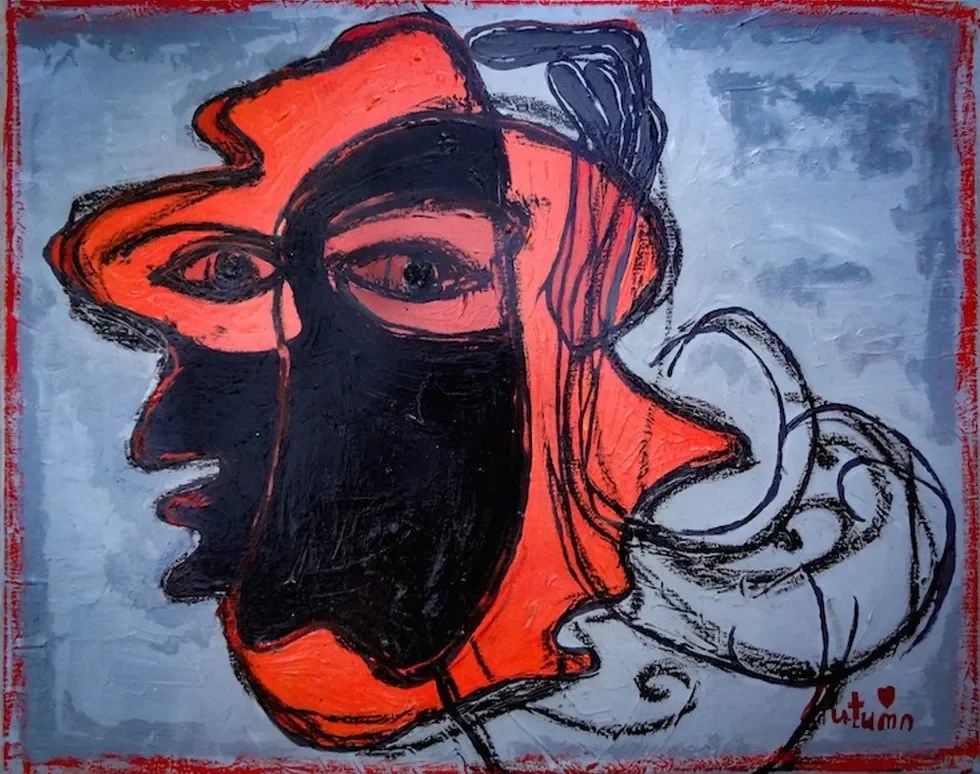

We make plays together at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility hidden away behind razor wire and 18-foot-high walls. We rediscover vulnerability and human connection behind faces masked for survival and inside guarded, broken hearts. We perform for the incarcerated population (please, not one more joke about the “captive” audience) and for a few hundred civilian guests.

Right now, we’re two weeks away from this year’s production, which is “Twelfth Night.” We’re telling a story about losing a brother, about heartbreak, about discovering what it’s safe to reveal, and what one has to conceal in a strange and possibly dangerous new place. We’re telling a story about not knowing when the joke has gone too far and the consequences of that — a story about wrongful incarceration. We’re telling a story about recovering what one thought was lost forever.

Me and the men in my theater group. Photo by the author, used with permission.

I’ve written before about how theater can teach trust, empathy, compassion, peaceful conflict resolution, deeper cognitive thinking, delayed gratification and how it can create community and understanding.

The men in Rehabilitation Through the Arts have far fewer disciplinary infractions inside the facility and a dramatically lower recidivism rate upon release than the general population.

I often wish I could take the guys to the theater.

You may be able to imagine that a fair number of these men had no access to the arts as children. We make do with production photos and the occasional “adapted for television” viewings.

That is, until the cast of Hamilton beautifully and powerfully performed their opening number from the stage of the Richard Rodgers Theatre for the Grammy ceremony and then performed again at the White House.

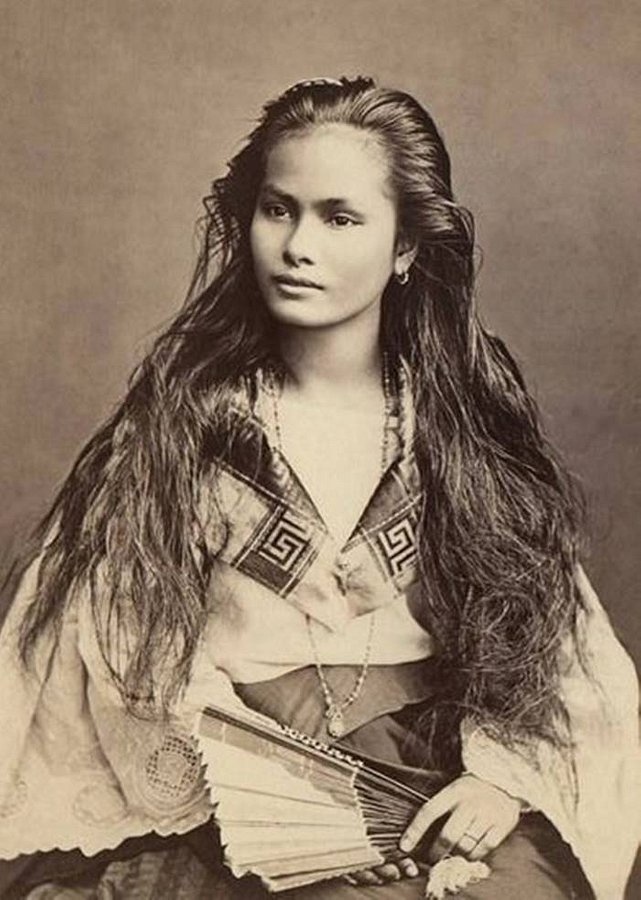

The Hamilton Cast at the Grammys. Photo by Theo Wargo/Getty Images.

When Lin-Manuel Miranda freestyled in the Rose Garden with President Obama, I promptly burned the performance onto a DVD and waited for clearance to bring it into the facility.

We watched on video as Miranda performed a piece from his “concept album” at the 2009 White House Poetry Jam, and then we talked about how that audience received his work.

We talked about what happens when people laugh and you’re serious, about the decision to stand one’s ground and follow one’s purpose, which is a hot topic in our rehearsal room as we get closer to sharing our months of work with the population of the prison.

One of the men observed, “He gets more confident as he goes.” Some of the men worry the population won’t understand Shakespeare; some worry they will laugh at the serious parts. One of the elders in our circle said, “We have to tell the story.”

We watched a true Broadway show in the big house.

Well, four minutes of one anyway, in the form of the Grammy performance of “Hamilton” from the stage of the Richard Rodgers Theatre. Heads nodded to the beat; some of the men snapped along. “Can we watch it again?” We could. We did.

We talked about how “Hamilton” is performed on a bare stage, just like we’ll perform “Twelfth Night.”

“No one laughed when he said his name this time.” We talked about how Miranda uses language, leverages rhetoric to find each character’s voice, just as Shakespeare did. We talked about working for six years on something you believe in, and we speculated about the long, uncertain nights he might have had somewhere in the middle of year three or year four.

These men know more than the rest of us can imagine about long, uncertain nights in the middle of a very long bid to survive.

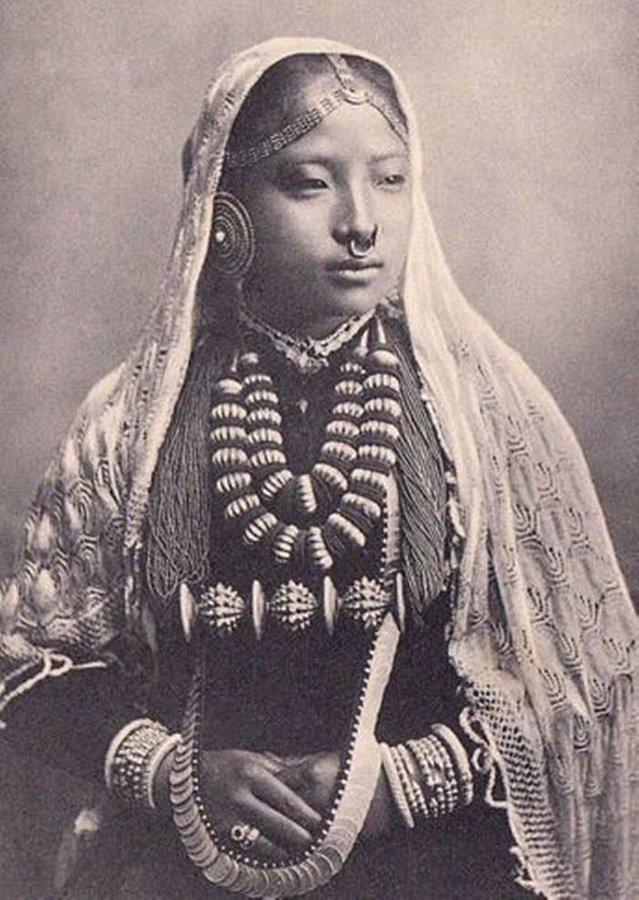

Opening night at Hamilton. Photo by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images.

We watched the cast perform “My Shot” at the White House. We whooped. We joyfully beheld the son of Puerto Rican parents and the first African-American president freestyle in the Rose Garden. We cheered. (One or two of us might have teared up, but we don’t need to discuss that.)

These gorgeous, thoughtful, wounded men rarely see themselves represented in the world.

As they fight to become the men they want to be, they still mostly see themselves in the narrative as junkies, dealers, thugs, or the latest black man brutally gunned down in the streets by the police. According to an Opportunity Agenda study, “negative mass media portrayals were strongly linked with lower life expectations among black men.”

“Who lives? Who dies? Who tells your story?”

But, in the midst of our shared creative endeavor, they saw themselves smack in the center of the narrative of creation, possibility, pursuit, and achievement.

Representation unabashedly made me weep as I watched a few of the men lean in.

Representation matters. Representation is beautiful.

And I am not willing to wait for it.