Doctors are surprised by unexpected stowaway during routine colonoscopy: a ladybug.

It was probably ensuring good luck for the unsuspecting patient.

Doctors are surprised by unexpected stowaway during colonoscopy

Getting a colonoscopy is not something anyone looks forward to doing. You have to spend three days prepping for the procedure which includes drinking a "bowel preparation solution." That's just a fancy way of saying "taking an extremely powerful laxative that will have you lying on the bathroom floor too afraid to move because you finally expelled the gum you swallowed in third grade."

Doctors and their fancy words to describe gross things, am I right? But hey, everybody poops. There's even a book about it for parents to read to toddlers who are potty training. The purpose of spending two days counting the tiles your sweat drips onto in the bathroom is to clean out your colon before doctors insert a camera to look for polyps, cancer, and other medical conditions. But when a patient went in for their appointment, doctors discovered something they didn't expect to find: a stowaway that had, somehow, survived the tsunami of poo.

The patient was a 59 year old man who was being seen for a routine colonoscopy, the procedure where they take a small camera equipped with a light and send it up to traverse the colon and large intestine. It's a procedure that becomes part of a full preventative workup once you reach the age of 45 if you're at average risk for colon cancer according to MD Anderson Cancer Center (though doctors are now recommending colonoscopy screenings begin sooner due to rising cases of colon cancer in young people according to the Cancer Research Institute).

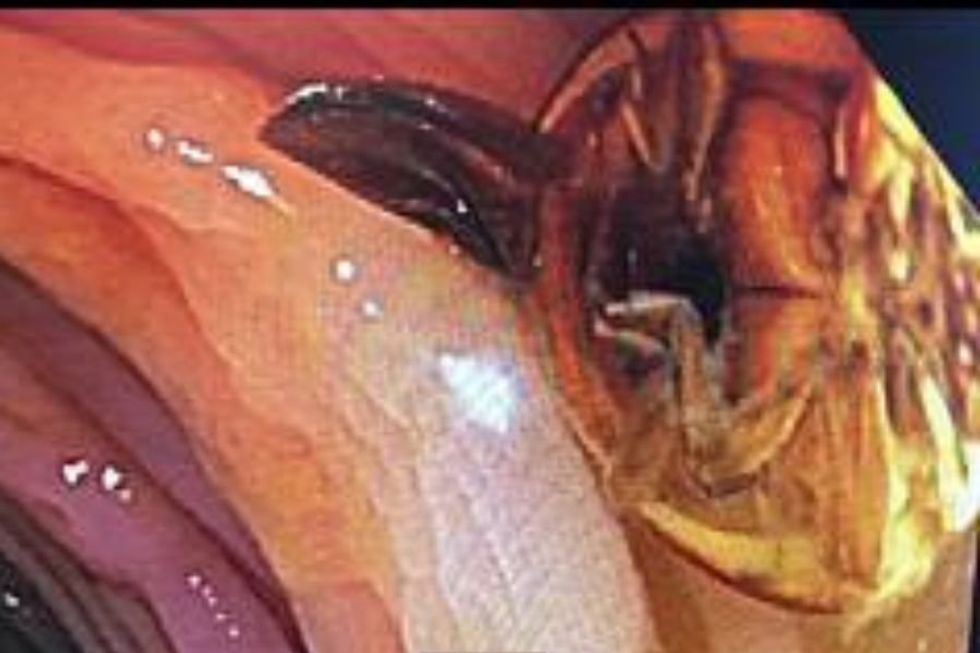

When the camera rounded the bend, it caught a clear sight of a perfectly intact ladybug who, despite the likely terror it experienced, was still alive.

The findings of the patient's friendly colon passenger was reported in the 2019 ACG Case Reports Journal complete with pictures of the spotted little fella just hanging out inside a human cavity. While the doctors have no way of determining how the ladybug wound up inside the man's body, they believe it was likely swallowed accidentally and escaped the wing destroying stomach acid due to the bowel preparation solution speeding up the process. The ladybug likely felt like it was on a weird waterslide or, if it's seen The Magic School Bus, it might have assumed Mrs. Frizzle had something to do with its unexpected adventure.

“The patient's colonoscopy preparation was 1 gallon of polyethylene glycol the evening before colonoscopy, and the colonoscopy examination was otherwise normal,” the authors of the journal write. “His colonoscopy preparation may have helped the bug to escape from digestive enzymes in the stomach and upper small intestine.”

If you're going to have a bug hang out in your poop chute, a ladybug is likely the preferred unexpected guest. Gastrointestinal specialist Dr. Keith Siau likes to share the things he and his colleagues have found inside patients and a ladybug is probably the least gross option for critters. He's found ants, cockroaches, and bees (yes, bees that help pollinate flowers and sting people who disturb their important business).

People cannot get over doctors finding bugs in people's colons during colonoscopies, while others have jokes about the random bugs found inside people. One person writes, "Oh, that’s just the magic school bus. They transformed into a lady bug for the field trip."

"Don’t take it out until you play the power ball," another says.

"Taking the title of invasive species a little far," somebody jokes.

No creature left bee hind 😜 https://t.co/VR70DtI15s

— Keith Siau (@drkeithsiau) June 23, 2025

"So I already worry about bugs getting into my ears, now I gotta worry about bugs up my butt? I hate it here," another cries.

"I’ve always had a fear of ingesting a bug or parasite and them finding it one day. I know that’s crazy but I think about it often. Seeing this affirmed my fear of the unknown," someone else shares.

"I could have gladly lived the rest of my life without knowing this." one person writes.

Well, if you're due for your routine colonoscopy here's hoping they don't find any unauthorized critters and you get a clean bill of health.

Guys won't recognize flirting unless it looks like this.

Guys won't recognize flirting unless it looks like this. How many ways are there to say No?

How many ways are there to say No? Do guys get hit on after 30? No, no, no, and no.Reddit

Do guys get hit on after 30? No, no, no, and no.Reddit For the record, I still love Scrubs.

For the record, I still love Scrubs. And they're off to the races!

And they're off to the races! Having healthy sperm is way more important than most people realize.

Having healthy sperm is way more important than most people realize. Butt jokes galore in Ryan Reynolds' Deadpool

Butt jokes galore in Ryan Reynolds' Deadpool Ryan Reynolds shows we shouldn't be scared of a camera "up our ass"

Ryan Reynolds shows we shouldn't be scared of a camera "up our ass" Rob loves it.

Rob loves it.

Sometimes gym bros are the best bros.

Sometimes gym bros are the best bros. This is how you move when you're in shape

This is how you move when you're in shape We can't all have abs like Usher

We can't all have abs like Usher