Gen Xer's old-school paddle photo brings back vivid memories, and wow, times have changed

Yes kids, this was a real thing.

The holes were for added speed and force, believe it or not.

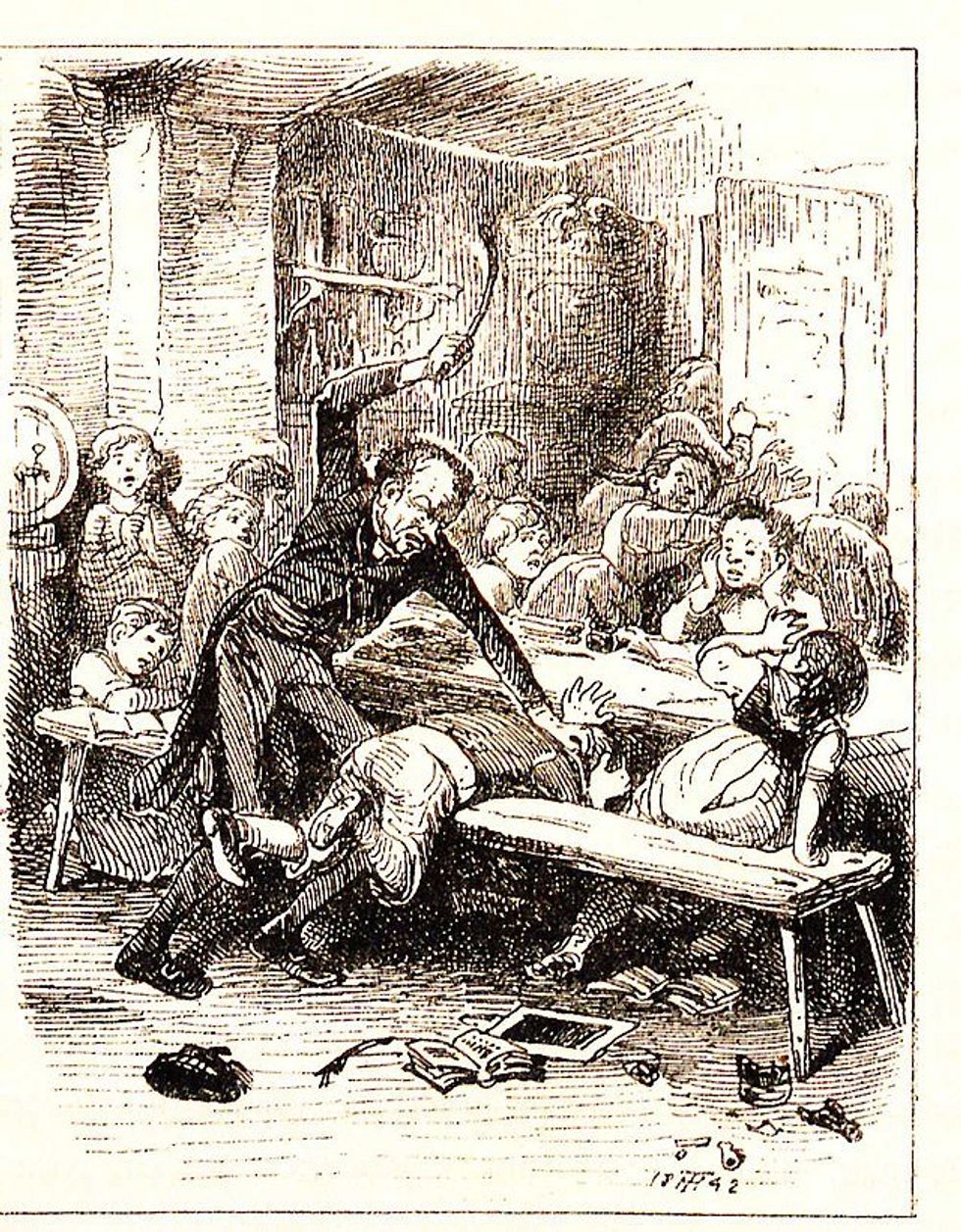

Gen X childhoods are often portrayed as somewhat idyllic, filled with feral freedom and hours of screen-free adventures in nature. A certain amount of that portrayal is true, and yes, it was often as glorious as it sounds. But there were some not-so-great things about growing up Gen X and older, too, that might shock some of the younger folks.

For instance, corporal punishment in schools was common. Not only were teachers and administrators allowed to discipline kids, but they sometimes did it by hitting them with paddles. "Hacks" or "swats" or "licks" they were often called, with kids essentially being spanked—but with hard objects. Many people of a certain age have stories of kids being sent to the principal's office to endure a number of hacks by an adult who, for some baffling reason, felt it was perfectly acceptable—necessary, even—to beat a child with a heavy piece of wood.

It's surreal to imagine it now, isn't it? A (now-deleted) photo shared on Reddit of a paddle with holes in it (for greater speed and force due to less air resistance) threw Gen Xers and any Boomers reading into a vivid memory spiral as people shared stories from their own experiences. Not everyone got the paddle—some got hit with yardsticks, switches, and other objects—but it's clear that corporal punishment (i.e., physical violence inflicted in the name of discipline) was commonplace during that era.

As people shared:

"My fifth grade teacher had one like this — he called it 'Count Whistler.'"

"The worse part is some student made it for credit in shop. That's the part I never got over."

"Ha! Yep. THAT thing! Good grief. Memory flood. Hung in Mr Flanagan's office beside the doorway. Fortunately, I was only a one-time recipient. Don't even remember why. Something minor and unintentional.

"But, the holes...THE HOLES! They possessed a mythical foreboding power, combining rough-shot aerodynamics, 1970s ambivalence, delivered randomly with casual sadistic intent!"

"I was never paddled but others were. One girl was so scared, she threw up on the principal. Good times."

"I got switched the 3rd day of kindergarten. Hated school every single day afterwards."

"I remember kids getting smacked on the palm with a yardstick in front of the class in kindergarten. They had to stand there with their palm up waiting for the blow. Seeing kindergarten age kids now I just can’t fathom how anyone could do that to a little kid."

"I was hit in the ass with a black-square metal device as punishment. It was In front of the whole school (we had to line up by class) by after recess. And yes by the school principal. And no it was not my fault. Still hurts to this day. More psychological than anything."

"I had severe ADHD (still do) and was paddled regularly, often harshly and for reasons I didn't understand. Eventually they gave up on the beatings and just stuck me in the hallway and forgot about me. That was when I actually started learning things, sneaking into the library to read whatever I could."

"Kids used to be paddled in front of school assemblies - it was terrible. It was the era of 'tough love', which gave cover to blatant abuse."

If you're wondering how parents allowed schools to hit their children, some did and some didn't. There were often permission slips sent home requesting parents to consent to such "discipline" methods, and parental attitudes were all over the map.

"My school required a parent to sign a form allowing them to 'discipline' a student. My mom was 'Hell No!' My mom would have shown up and paddled them."

"I spent most of my life in the northeast, where this didn't happen, so imagine my surprise during my brief stint in a Florida school when I got caught chewing gum and was sent to the principal's office to be paddled. I told them they had better call my mother first, which they fortunately did.

My mother, who was not a woman to be trifled with, told them if they laid a finger on me they would be sorry beyond anything they could imagine and that we came from 'a civilized place' and she couldn't believe anyone thought it was okay for 'some old pervert to put his hands on a teenage girl's ass.' I did not get paddled."

"My pops, who at the time did believe in a bit of corporal punishment for certain offenses, wrote them a nice note to go with the refusal which I only found out about years later. 'To whom it may concern, my penmanship sucks because the nuns at my school beat me for writing with my left hand even though I am naturally left handed. Not only do I deny you permission to strike my children I will send anyone who does so to the hospital.' Dad was actually a fairly chill guy but I have no doubt he meant every word."

"My school required the same and my mom informed me she was going to sign it as the principal insisted. At 8 years old I looked her straight in the eyes and said they would have to call the police cus I wouldn’t be going down without a fight. My mom did not end up signing it."

"At my elementary school they called them 'swat slips.' Well, I got one and was supposed to take it home for my parents to sign. Being a 9 year old girl, I was not down for a swat from my middle aged vice principal. The next day, I returned it unsigned and declared that my dad said he would discipline me at home. The school called my dad to verify this. He did take care of it at home and beat my bare ass with his leather belt. I should have taken the swat."

As of 2024, corporal punishment was still legal in 17 states and practiced in 14, according to the National Education Association. Six additional states have not expressly outlawed it. While the violent discipline method has fallen out of favor for the most part, it's not gone.

Roughly 69,000 students received corporal punishment in the 2017-18 school year, nearly 40,000 fewer than in 2013. The pandemic disrupting in-person schooling likely had an impact on the most recent number available—about 20,000 students in 2020-21—but even those numbers might be shocking to those of us who assume that paddling children had become a relic from a bygone era.

And lest there be any question as to whether the practice is bad, The World Health Organization has classified corporal punishment as “a violation of children’s rights to respect for physical integrity and human dignity, health, development, education and freedom from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Of course, there are people who try to argue that moving away from corporal punishment is "what's wrong with kids these days," but there's a whole ocean of options in between beating a child and having no school discipline whatsoever. Fear of bodily harm is not a necessary component of learning how to behave in a civilized manner, and corporal punishment has been shown time and again to do more harm than good.

But we don't even need those studies to know that paddling kids was wrong. Reading through Gen Xers' responses to the paddle photo, it's clear that the vast majority aren't even remotely grateful for the experience, but rather appalled that it ever happened in the first place. Hitting a child with what is essentially a bat on the arms or legs or back would be considered child abuse, but hitting them on their bottom—which we tell kids is a private area—was somehow not child abuse? There's no way to make that make sense.

Thankfully, we've learned a lot over the decades, but the fact that these things are still used anywhere is shocking.