The famously cool NATO alphabet—Alfa, Bravo, Charlie—has a surprisingly genius history

Proof that simpler isn't always better.

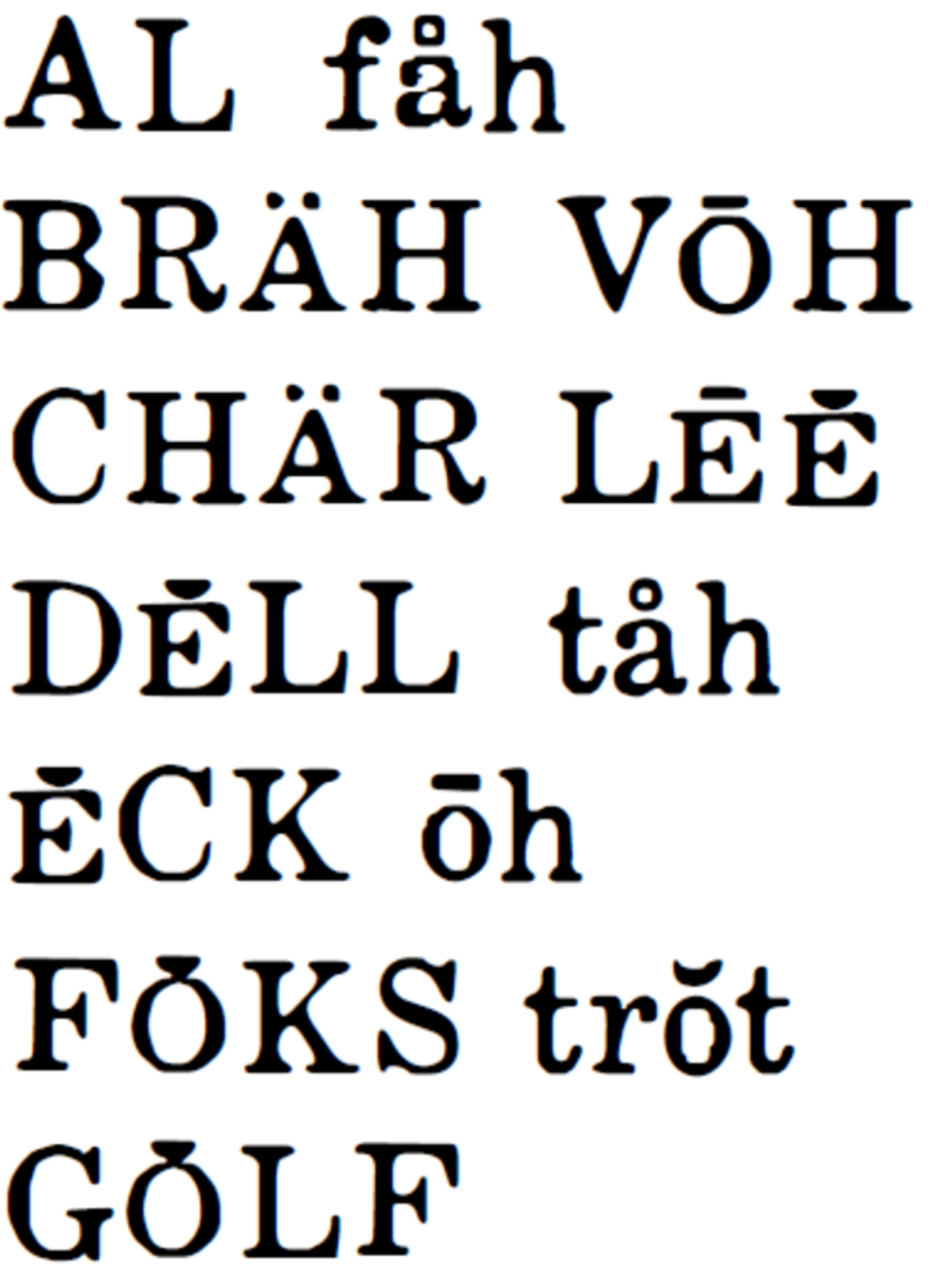

Typographic mural by Jeff Canham using the first nine words of the NATO's phonetic alphabet

When you have to spell a name over the phone, you've likely had to use something akin to the NATO alphabet, even if you haven't used the exact same words. "E as in elephant, D as in David," etc. When we watch movies involving airline pilots or military personnel, we often hear the real NATO alphabet, which starts Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, and so on.

Using words to represent letters was a brilliant idea to solve the problem of trying to spell things out over early telephone wires, which often made for crackly connections where letters could easily be misunderstood. But the full history of the NATO alphabet is much more fascinating than one might guess, as BBC journalist and self-described "word nerd" Rob Watts explained in a video.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

Watts explains that the 26 words of the NATO alphabet were "meticulously chosen as part of a secretive process" after WWII. The idea began with the invention of the telephone, when a version of a spelling alphabet was created within the telecom industry. Soon militaries around the world were using their own versions of such an alphabet, which resulted in the rather chaotic reality of every different branch of the armed service in Britain and the United States utilizing entirely different versions.

Clearly, a standard needed to be created, and WWII was a prime opportunity. However (and perhaps unsurprisingly), the two countries couldn't agree on what alphabet to use. Watts explains that a report for the U.S. Air Force later described the compromise that was rushed through: “The Generals and the Admirals went down the list taking first a U.S. and then a U.K. preference to complete the list and get on with the war.” What they came up with was known as the ABLE BAKER alphabet.

So that took care of the military. But around the same time as the end of WWII, the aviation industry boomed, and in 1944, a convention resulted in 52 nations establishing an international body that would oversee non-military aviation. The International Civil Aviation Organization, or ICAO, (which still exists today) adopted the ABLE BAKER alphabet at first, but it soon became clear that that alphabet didn't work very well for the members of the ICAO who didn't speak English.

The alphabet needed words that had more universal appeal. A linguist at the University of Montreal, Professor Jean-Paul Vinay, was tasked with coming up with a new alphabet, which had to meet five criteria:

1. It had to be a live word in each of the three working languages of ICAO—English, Spanish, and French.

2. It had to be easily pronounced and recognized by airmen of all languages.

3. It needed to have good radio transmission and readability characteristics.

4. It had to have a similar spelling in at least English, French, and Spanish, and the initial letter must be the letter the word identifies.

5. It had to be free from any association with objectionable meanings.

That's how we ended up with so many Greek letters, including Alpha, which Vinay spelled ALFA to make it more phonetic. He also made Juliet more phonetic for the French by adding an extra T. A few changes were requested after Vinay submitted his alphabet, which resulted in POLKA becoming PAPA and ZEBRA becoming ZULU.

That fixed everything, right? Sure, except that most people who had to use it hated it. Many of the words were longer than the ABLE BAKER alphabet, which had many one-syllable words, whereas GOLF was the only one-syllable word in the ICAO alphabet. However, those multi-syllable words proved more effective, since a small glitch in communications would be less likely to make them unintelligible.

The new North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO, showed an interest in using the alphabet, so a study was done to make sure that the ALFA BRAVO alphabet really was better than ABLE BAKER. The ICAO commissioned Ohio State University to compare the two alphabets, and the result was clear: ALFA BRAVO wins. However, some additional research showed a few changes were needed, which ultimately resulted in this alphabet finalized in 1956. It's technically the ICAO alphabet but is often referred to as the NATO alphabet.

Pretty nifty, eh? People working together with the input of experts and support of research generally leads to helpful progress, and while the NATO alphabet may have its pain points, it's infinitely better than the haphazard way we used to tell people how to spell things clearly. Yay, humans!

You can watch Watts' entire video on his RobWords YouTube page here.