Ralph Pace’s career as a photographer didn’t start underwater. In fact, it started with a jaguar.

He’d decided to go to graduate school for oceanography, but before he could do so, he needed to get some research experience under his belt.

So he headed to Costa Rica.

“I was working on sea turtle projects, but it’s also one of the only places in the world that jaguars actually hunt in packs,” he says. “I called my brother and said, ‘Hey man, you won’t believe this!’ And it was kind of a typical brother thing — he sent me a camera and said ‘Prove it!’”

Pace didn’t grow up knowing he wanted to be a photographer, much less an underwater one. In fact, he was pre-med in college and hadn’t even been on a dive until he traveled abroad to Australia.

But once he realized the ocean was his calling, he headed to Scripps Institute of Oceanography. And after his encounter with the jaguars, he quickly realized he wanted to pair his newfound photography skills with his love of the ocean.

It didn’t take long for Pace to turn his camera toward the water to start telling stories about conservation.

He already had a passion for the environment itself. And when he started doing photography work on conservation projects, he quickly discovered a strong preference for working with scientists when taking his photos.

“They’re gonna show you the best stuff in the best way, in such a way that you know you’re not harming any animals,” he says. “Those are really the guys on the front lines of conservation.”

He started reaching out to scientists he already knew from his graduate work at Scripps and began going on projects involving sea turtles, sturgeon, swordfish, and more. Slowly, he went from simply documenting the projects to actually using his photos to tell important stories that he felt people needed to hear — landing him on the front lines of the conservation movement too.

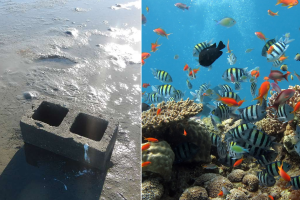

Pace doesn’t take photos of just anything — he goes out of his way to find stories that no one has heard and bring them to light.

In many cases, that means traveling to places that most people can’t reach and will likely never get to see themselves.

“You show people this incredible world that they kinda didn’t even know existed,” he says. After all, “How do you get somebody excited about something if they can’t picture it, can’t relate to it?”

By bringing unreachable sights to people through his photos, Pace is able to bring the support to the causes they represent — like ocean conservation.

And that, he says, is the power of photography.

“With photos you have a really unique opportunity to grab someone’s attention,” he says. “You take a famous photo of, say, the ‘Afghan Girl’ that Steve McCurry took for the cover of National Geographic. You take that picture, and it grabs everyone’s attention and they read an article about it, and at the end of it people are sending millions of dollars to refugees abroad.”

Being a photographic trailblazer doesn’t always mean traveling the world though. Sometimes, it means staying put and finding stories nearby.

“I think you’re a lot more valuable if you can work in your backyard and tell stories that are close to home,” Pace says. “I tell people I’m going out to work with sea turtles in San Diego and they say, ‘There are no sea turtles here!’ They’ve lived here their whole lives and they don’t know there’s a population of sea turtles here.”

Pace’s mission is to bring untold stories to light, and sometimes those overlooked stories are nearby.

He’s just one man, but Pace is confident that his stories can have a big impact on ocean ecosystems.

Ocean conservation is a huge and complex movement, full of giant and sometimes overwhelming problems. But even one story about one particular animal can have positive effects on the whole environment.

“Sometimes, by saving one thing, we create a sort of umbrella to save a lot of things underneath it,” Pace says.

He uses Costa Rica, where he worked with sea turtles but also saw jaguar conservation efforts, as an example. Oftentimes people can feel like they’re competing for resources in order to save their species, but the way Pace sees it, it’s all one story.

“Why work in competition with the jaguar folks?” he says. “Let’s protect the whole stretch of beach. Let’s work together to make sure there’s lots of sea turtle habitats so that when their populations rebound, it also provides food for the jaguar.’”

He brings that same philosophy to all the projects he photographs. By bringing one untold story to light, Pace’s photography can attract support and resources to entire ecosystems.

Though photography is a pretty specific skill, Pace’s passion for new information is something we can all incorporate into our lives.

Spreading the knowledge of ocean conservation — whether though photography, writing, science, or just talking over the dinner table — is how Pace believes we will ultimately save our underwater environments.

“That’s what telling stories can do,” he says. “You take people to places they’ve never been and you introduce them to things they’ve never heard about. And hopefully that allows to them to make better decisions that are ultimately gonna make this planet a better place. That’s all you can really hope for.“