As thousands across the nation prepare to take to the streets on March 24, 2018, for The March for Our Lives, we’re taking a look at some of the root causes, long-lasting effects, and approaches to solving the gun violence epidemic in America. We’ll have a new installment every day this week.

I was teaching in a high school classroom when the Columbine shooting happened.

In between periods, a student rushed into my room and turned on the television. As other students shuffled in, they caught the scene on TV and stopped in their tracks.

Together we gaped silently at aerial footage of teens pouring out of their school, covered in their classmates’ blood. News reporters struggled to offer details about the shooter or shooters, still unclear if the carnage had ended. Still unsure of the body count.

I looked around at my 15- and 16-year-old students, their eyes wide with a mix of shock and fear. Even the goofy class clown stared somberly at the screen. I considered whether it was prudent to let them see all of this, but the only difference between that high school and ours was geography. Those bloodied students could have been my students. They knew it, and I knew it.

It seems commonplace now, but that was a feeling I’d never felt as a teacher before. And I’d only felt something similar once as a kid.

I remember when I was little, sitting huddled in a ball under my desk, imagining the classroom around me exploding.

It was the early 1980s. I must have been 6 or 7. My class was doing a nuclear-blast preparation drill, a hallmark of the Cold War era in which I was born. I remember staring at the thin metal legs of my desk, wondering how they were supposed to protect me from a bomb going off.

Nuclear annihilation — not being gunned down in school — was the big concern of my childhood. Such duck-and-cover drills disappeared by my middle elementary years, so the threat felt short-lived. Of course, a nuclear blast is always a terrifying thought, but somehow, I just knew it wasn’t likely to happen.

I imagined it, though. And the imagining alone shook me as a young child. Sometimes I look back and wonder how Americans lived like that for so long.

Kids in high school now have been doing active-shooter lockdown drills their entire childhoods.

The year after Columbine, my husband and I started our family, and I left teaching. I chose to homeschool my kids, and though lockdowns weren’t part of that decision, the lack of active-shooter drills has been a significant perk of homeschooling.

Unlike nuclear preparation drills, active-shooter drills are meant to prepare kids for something they know has happened multiple times. They’ve heard the news stories. Some kids have been through the real thing themselves.

I try to imagine it — my sweet 9-year-old boy huddled in a closet with 20 of his classmates, forced into unnatural silence as they wait for the sound of a would-be shooter trying to enter their locked classroom. I can see his face, the very real fear in his eyes. I can honestly feel his racing heartbeat.

It guts me just to think about it.

An elementary school teacher (who requested anonymity because the internet is ridiculous and she’s received death threats) posted a description of a recent active-shooter drill in her classroom. The post has been shared close to 200,000 times and for good reason. It’s a simple description of an unfathomable reality.

“Today in school we practiced our active shooter lockdown. One of my first graders was scared and I had to hold him. Today is his birthday. He kept whispering ‘When will it be over?’ into my ear. I kept responding ‘Soon’ as I rocked him and tried to keep his birthday crown from stabbing me.

I had a mix of 1-5 graders in my classroom because we have a million tests that need to be taken. My fifth grader patted the back of the 2nd grader huddled next to him under a table. A 3rd grade girl cried silently and clutched the hand of her friend. The rest of the kids sat quietly (casket quiet) and stared aimlessly in the dark.

As the ‘intruder’ tried to break into our room twice, several of them jumped, but remained silently. The 1st grader in my lap began to pant and his heart was beating out of his chest, but he didn’t make a peep.”

Seriously. These are babies we are putting through this. (Well, not literal babies, but still.)

And these drills can be even more terrifying than you might imagine.

At a high school in Anchorage, Alaska, an officer used the sound of real gunfire — blanks shot from a real gun — during active-shooter drills. The idea was that kids would learn what actual gunfire sounds like so they can act quickly when they hear it.

“We don’t want to scare them,” the principal, Sam Spinella, told CNN affiliate KTVA. “We want this to become as close to reality as possible.”

I am dumbfounded. Those two sentences make zero sense together. We’re not talking about a police training academy here — we’re talking about an average day in high school. The reality they are trying to prepare them for is scary — how could a preparation “as close to reality as possible” not be?

A recent article in The Atlantic examined the psychological effects of active-shooter drills on kids. Surprisingly, not a lot of research has been done on the subject. All we really have are reports of young adults who grew up with them.

One interviewee described a memory of his classmate coughing during a lockdown drill when he was 12. Their teacher reacted by telling the class that in a real shooter situation, they’d all be dead now.

Yeah, probably not the best way to handle that.

But what is the best way to prepare children for the possibility of a gunman trying to kill their classmates, their favorite teacher, their best friend?

We want kids to feel safe and secure. We don’t want to scare kids as we prepare them for something that is undeniably scary. But is it smart to scare them a little bit in order for them to understand the seriousness of the drill? And if kids aren’t scared at all — if they are totally unfazed by active-shooter drills — how can we justify them being so desensitized?

Ugh. This is not normal. This should never feel normal.

And yet, this is normal. In fact, some people tell me they feel comforted by the preparation.

I talked to a handful of teens and young adults who grew up with lockdown drills. One described a series of bomb threats at her high school, which she said were scary at first, but eventually became a “boy who cried wolf” situation. Another described intruder drills as simply preparing for the unexpected, not much different than an earthquake or tornado drill.

One high schooler, Joe Burke of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, told me about the first lockdown drill he remembers in the fifth grade. He and his classmates huddled under computer desks along the wall, knees hugged to their chests, with the lights off and door locked:

“When we were sitting under the desks, I had a slight bit of doubt in the idea. To my fifth-grade self, it didn’t seem like the best idea to just be hiding if someone were to come in and try and hurt us. It would only take a few seconds of searching to find 25-plus kids and a teacher all cramped under those tables. … At the time, I automatically assumed that the adults knew more than we did. I figured that we were much safer than I realize we actually were, in retrospect.”

Burke said the new ALICE training his high school has implemented has made him feel better prepared and is “a massive step in the right direction.” (ALICE is a for-profit training program that has been implemented in schools across the country. Here’s an interesting analysis of the praise and criticism of it.)

Joe’s mother, Christine Burke, said that she has made it a point to talk to her kids about active shooter situations in detail:

“After Parkland, I sat with my 15-year-old son and showed him the footage of the shooting inside the building. We talked about how the smoke from an AR-15 would disorient his way out, that the gun would be loud, that screaming classmates would make it hard to hear instructions. We talked about how his phone need not be a priority (no filming the scene, no taking pictures) but that he should use it as a means of communication only if he could. And we talked about how the ALICE training would feel in a real situation. That conversation with my son chilled me to my bones because I realized that this is the world we live in now. I have to talk to my son about his algebra grade and about how loud an AR-15 sounds when fired in a classroom.”

Christine, like many parents, finds herself navigating surreal waters. We have accepted the inevitability of school shootings to the point where we actively prepare our kids for them.

Generally speaking, preparedness is good. Preparedness is smart.

And yet, how can we accept that this is the reality for children in America? Parents across the country constantly say to themselves, “We shouldn’t have to do this. Our kids shouldn’t have to do this.” And yet, they do.

Is this really the price we have to pay for freedom?

We’re supposed to be a fantastic, developed country, aren’t we? We pride ourselves on being a “shining city on a hill” a leader among nations, a beacon of freedom to all people.

There is no official war happening on American soil. We are not a country experiencing armed conflict or revolution or insurrection. And yet we live as if we are.

People in other countries look at our mass shootings and what we’ve attempted to do about them and think we are out of our ever-loving minds. I’m right there with them. As a former teacher and current homeschool parent, I feel like I’m peering in from the outside with my jaw to the floor at what we’ve accepted as normal for our children.

I’m a fan of the U.S. Constitution and don’t take changes to it lightly, but maybe it’s time to accept that the Second Amendment has not actually protected our freedoms the way it was designed to. We are not a free people when our children have to hide in closets and listen for gunfire as they imagine themselves the next victims of a mass-murdering gunman during math class.

This is not normal. This should never feel normal.

Kids who have repeatedly and systematically prepared for carnage in their classrooms are taking to the streets, to the podium, to the media — and soon to the polls — in a way we haven’t seen in decades.

It’s easy to see why. These teens have spent their childhoods watching the adults in charge respond to the mass murder of children by simply preparing for more of it. And they’re done.

I’m unbelievably proud of the way these young people are organizing, saying #NeverAgain and pushing for effective gun legislation. Their efforts have convinced the governor of Florida to break with the National Rifle Association and sign a sweeping gun control bill. (Though not perfect, it’s a big step for the “Gunshine State.”) Companies feeling the pressure and momentum have broken ties with the NRA as well.

I can’t help but note how these kids’ successes highlight previous generations’ failure on this issue. The time for taking real action was long before Parkland, Sandy Hook, or even Columbine. But I feel the sea change coming.

These young activists give me hope that maybe future generations will look back in wonder at how we lived like this for so long.

For more of our look at America’s gun violence epidemic, check out other stories in this series:

- How the U.S. put an end to plane hijacking and why gun reform advocates should take note.

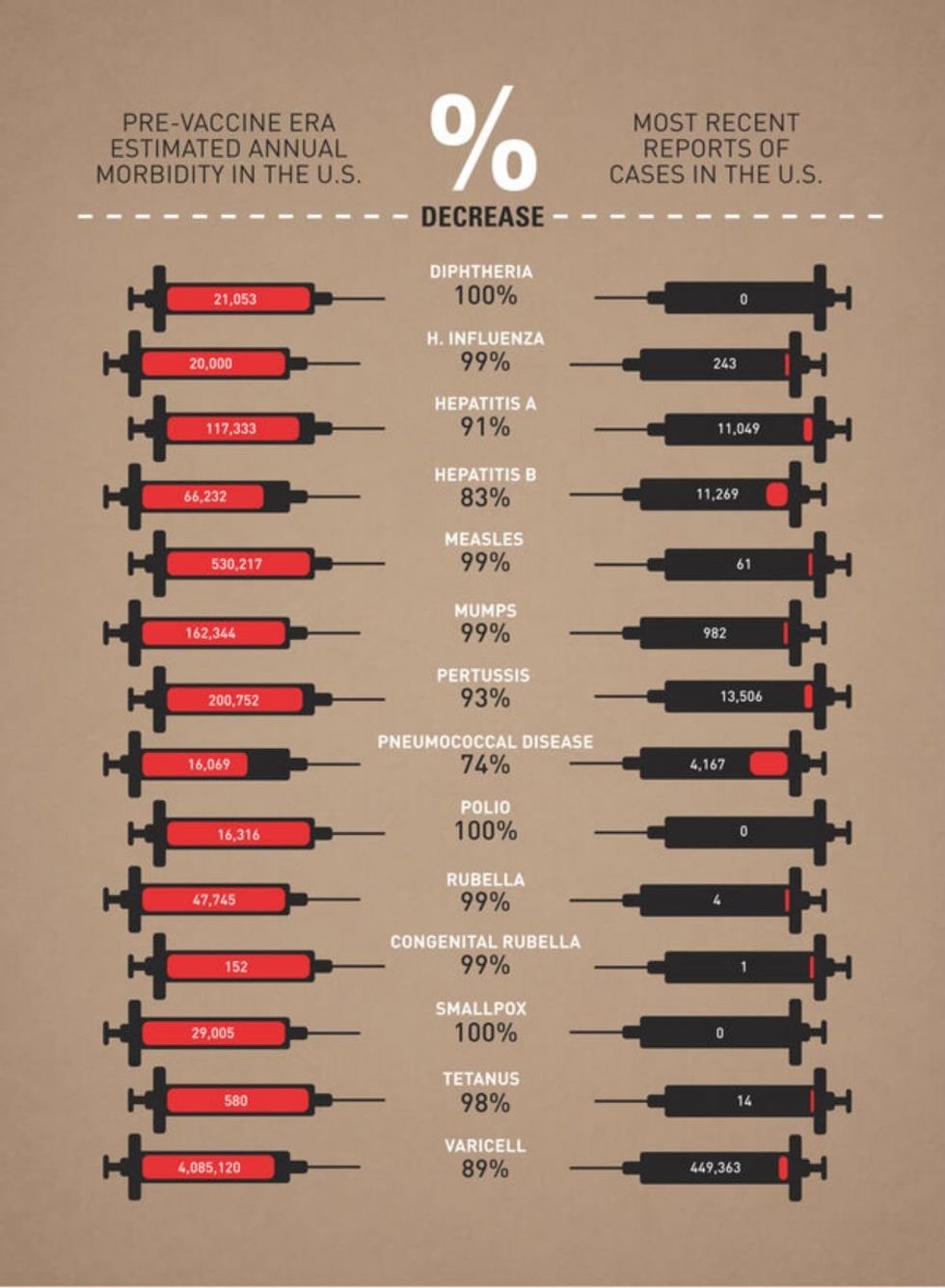

- The next time someone blames mass shootings on mental illness, send them this.

- Parkland kids are changing America. Here are the black teens who helped pave their way.

- Answer 3 questions to find out which gun violence action plan is right for you.

And see our coverage of to-the-heart speeches and outstanding protest signs from the March for Our Lives on March 24, 2018.