My son, Tate, and I just got home from the new Pixar movie, "Finding Dory."

Dory's character is a blue tang fish. Image via iStock.

It’s been on our calendar for weeks, as are most animated films. Movies are Tate’s "thing," and we rarely miss one he shows an interest in.

I had not seen the trailer for "Finding Dory," so I only knew that it was a Pixar film and a sequel to "Finding Nemo." "Finding Nemo" was a favorite of Tate’s when he was young, so much so that he has a lot of the dialogue memorized. I knew Tate was going to love the movie, but I did not expect to be overly interested myself. I had no idea that three blue cartoon fish, a couple of clown fish, and a grumpy octopus (make that a septopus) would draw me in and cause me to feel gut-wrenching empathy and compassion.

I found myself comparing Tate and autism to Dory and her own disability.

In the movie, Dory was unable to remember the things she needed to do to be successful and to keep herself from harm. I saw myself in the caregivers who surrounded Dory and tried to keep her safe.

As a very small fish, Dory’s parents tried so hard to surround her with rules and plans to keep her safe and ultimately, lead her toward success. They taught her rhymes and songs to help her remember the safety rules, how to repeat her name and her diagnosis, and they showed her how to get back home by creating a special marked path.

Still, Dory’s mother cried and worried because it might not be enough.

Image via Lisa Smith, used with permission.

I remember all the discrete trial programs we had for Tate, such as memorizing his parents’ names and his address. Those things meant nothing to him, but he could spout them if asked. In the autism community, we have T-shirts that help our kids tell others they have autism. There are ID bracelets available. We can buy signs for our cars and even stickers to put on their bedroom windows for rescue workers to see. Some of us also have service dogs and special locks on our doors. We are extremely careful.

And we still worry, too. What if?

Dory, as a young fish, could not advocate for herself or find help once she was lost. As an adult fish, she depended on others to keep her safe. At 14 years old, Tate cannot communicate well enough to advocate for himself among strangers nor would he know who to turn to and ask for help. Through no fault of her own, Dory made tremendous mistakes at times, and she felt guilty because she could not do the things she felt she should have been able to do.

I hear Tate constantly apologizing for things he cannot do because of his autism. And while I assure him that there is no need to apologize, my heart aches for him.

Nemo is a character that didn't give up on Dory, much like Tate’s friends at school. Nemo knew Dory was capable of more than she was being given credit for. He was supportive and patient, ready to help but willing to wait to see if Dory could do it herself, similar to how Tate’s friends encourage him and know just when to step in to help.

Nemo is based on a clownfish. Image via iStock.

Dory’s caretakers were understanding and patient with her most of time, but occasionally when things were tense, someone snapped at her, making her feel like a failure. At one point in the movie, Marlin criticized Dory, and it crushed her. This scene was telling of our own lives. It rarely happens in our home, but I’m not perfect. Marlin spent a few minutes in denial that he had said anything wrong, then much longer beating himself up for what he said. Once again, I saw myself in the animated character on the screen.

Marlin underestimated Dory several times in this movie. While she had special needs, there were some things she could do well. There have been many times I have doubted Tate and he has shown me just how wrong I was. At the end of the film, we saw Marlin trying so hard to trust in Dory like Nemo does. But even after he had learned his lesson, he still followed and spied from afar to make sure Dory was safe. And Dory knew.

Dory knew that Marlin was watching and there for her if she needed him, just like I will always be there for Tate.

It is such a fine line we walk — or swim.

Meatloaf was a staple dinner.

Meatloaf was a staple dinner. Spaghetti is still a classic.

Spaghetti is still a classic. Why were pork chops so popular?

Why were pork chops so popular?

Pluto and Goofy along with Chip and Dale. Photo by

Pluto and Goofy along with Chip and Dale. Photo by  Dogs aren't normally allowed onboard cruise ships unless they're service dogs, like Forest. Photo by

Dogs aren't normally allowed onboard cruise ships unless they're service dogs, like Forest. Photo by

Smiling girl chatting outdoors with a friend.

Smiling girl chatting outdoors with a friend. Smiling warmly in a cozy sweater, feeling relaxed and happy.

Smiling warmly in a cozy sweater, feeling relaxed and happy.

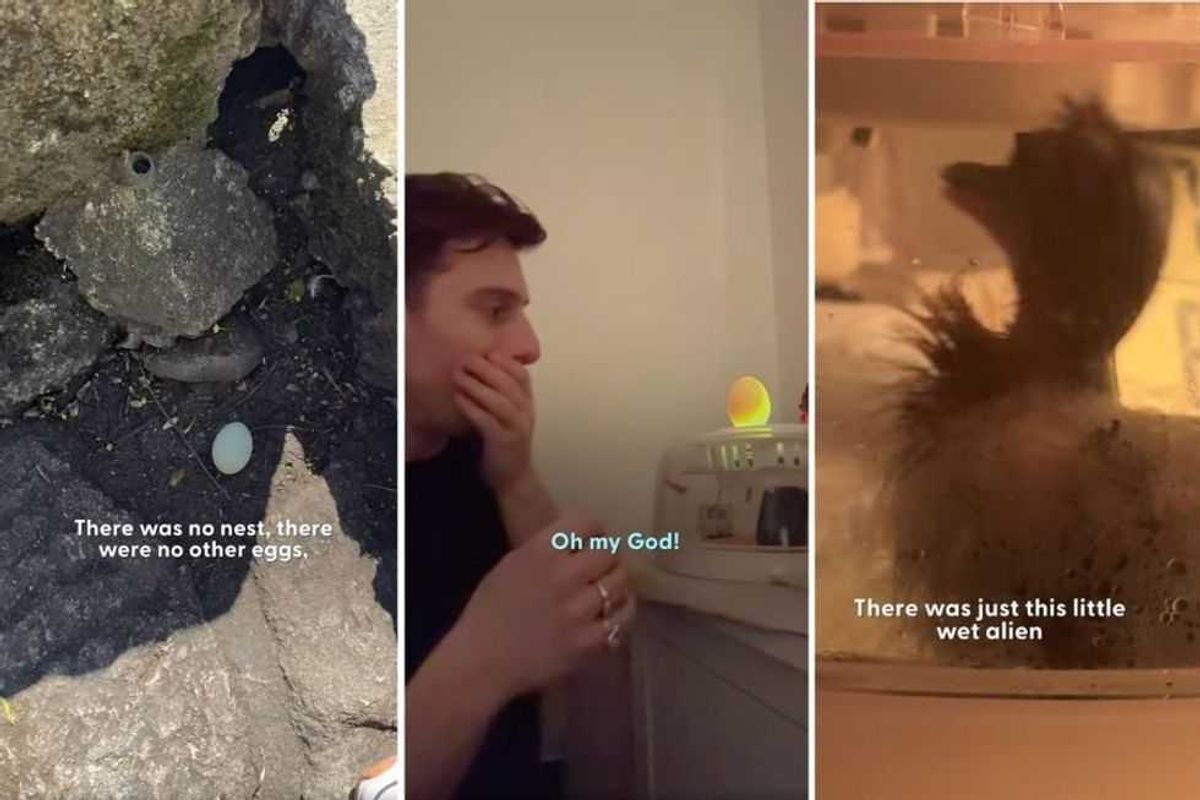

What do you do when you find an egg where it doesn't belong?

What do you do when you find an egg where it doesn't belong?

Sick woman in bed with thermometer, scarf, and hot water bottle on neck.

Sick woman in bed with thermometer, scarf, and hot water bottle on neck.