For one week each year, teacher Zach Carey turns his eighth-grade classroom into a working biology lab.

Students at Commodore John Rogers School in Baltimore, Maryland, walk into class on a Monday and find their room transformed. Two high-powered microscopes sit at the back of the class, and each group of desks is topped with a transparent tank occupied by two small, delicate fish: one male, one female.

For the next week, these kids will be scientists, and the fish are going to help them.

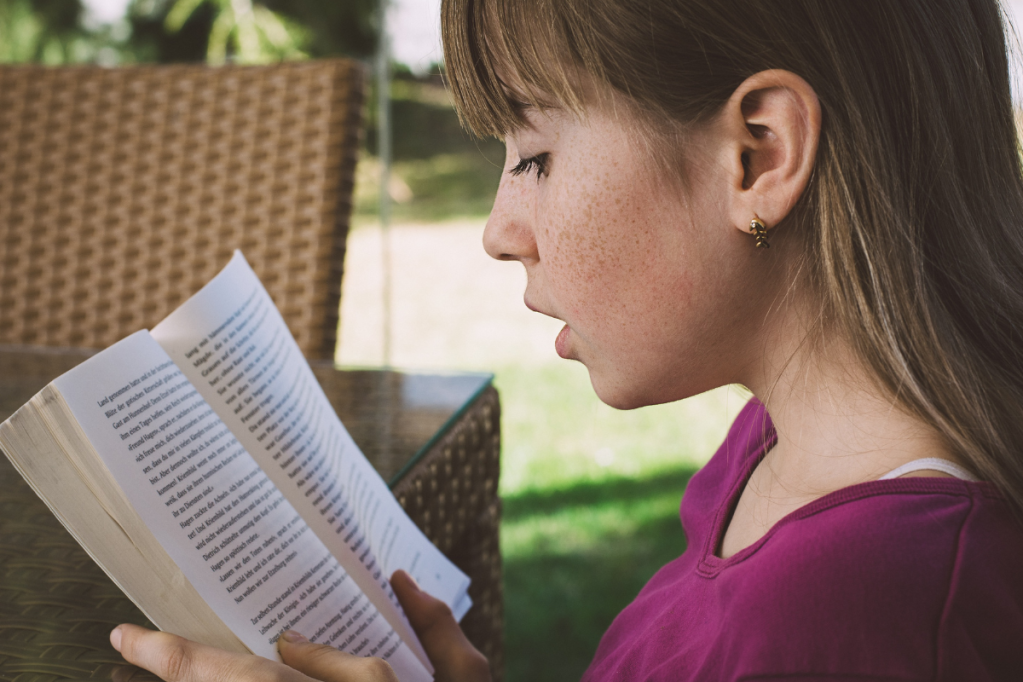

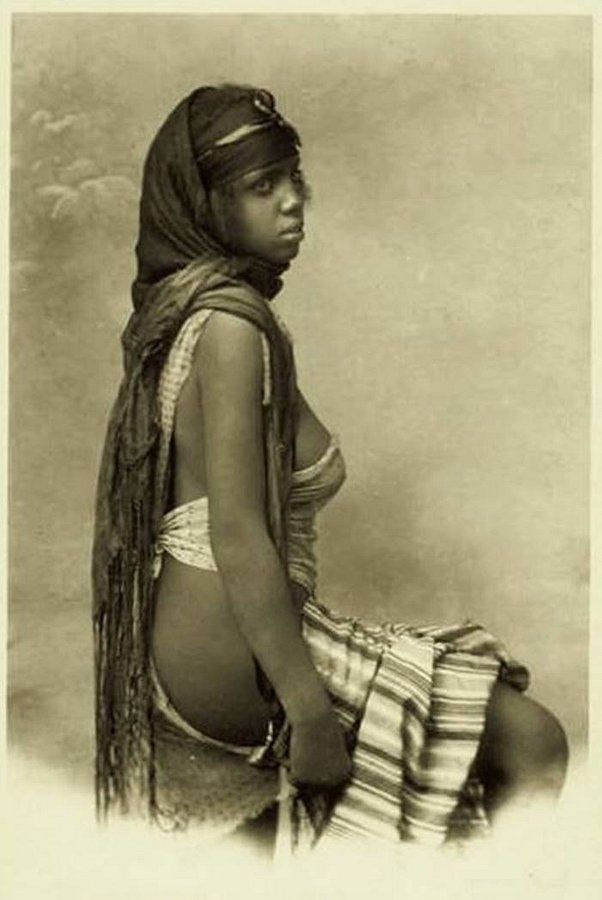

A third-grader at another nearby Baltimore school, Thomas Jefferson Elementary. Image from David Schmelick and Deirdre Hammer/Johns Hopkins University.

This week of hands-on science is thanks to a group called BioEYES, a nonprofit that uses zebrafish to give kids real experience as scientists.

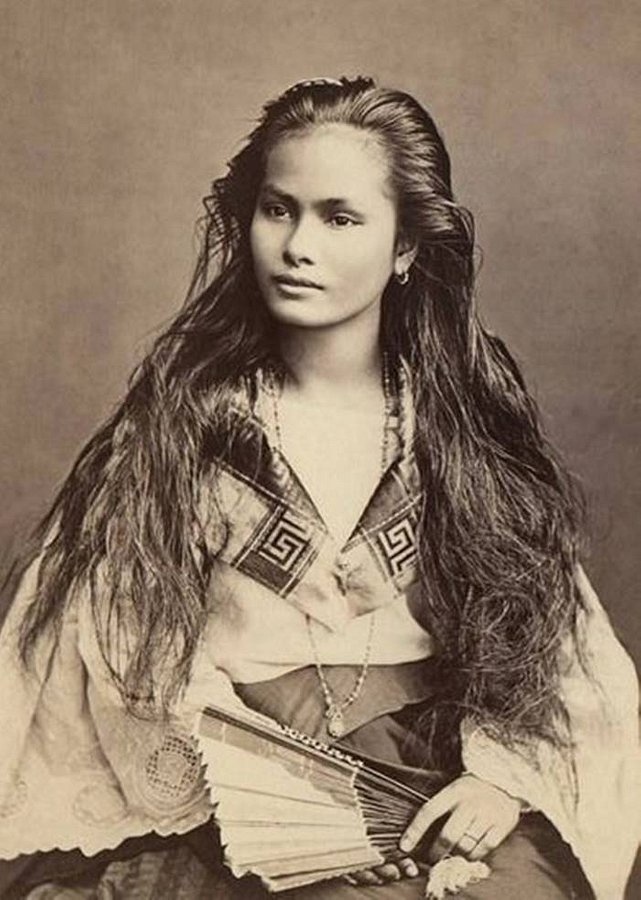

Zebrafish are small, striped, guppy-like fish and are often used in science experiments. The idea behind BioEYES is to have the two adult fish breed, then let the kids work as scientists and watch the embryos develop.

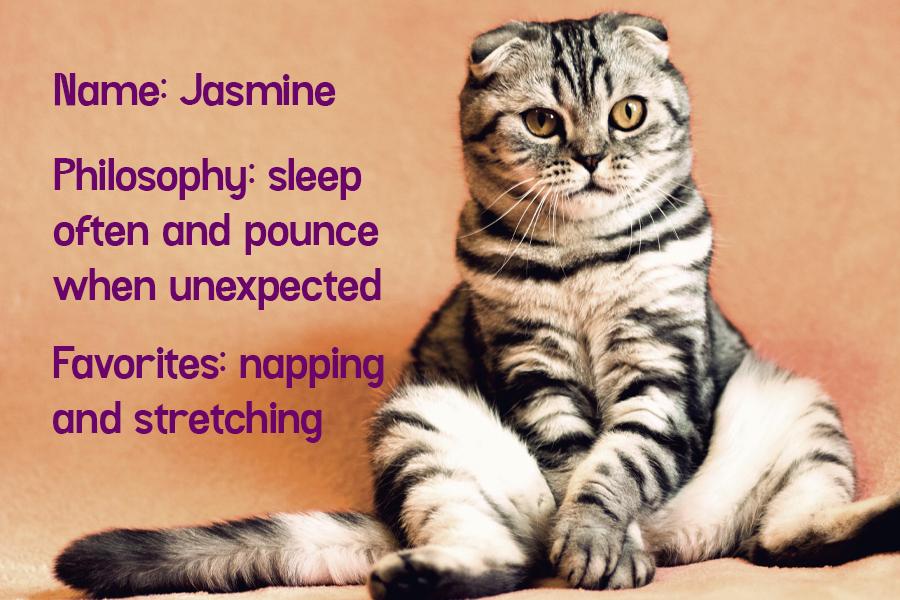

Adult zebrafish. Image from David Schmelick and Deirdre Hammer/Johns Hopkins University.

When you tell kids they’re going to be breeding actual live fish in a middle-school classroom, some seem amazed, but others are pretty skeptical, says Carey. So you can imagine the excitement on that Monday morning — excitement Carey quickly transforms into rapt attention.

“The kids are super engaged,” Carey says. “They want to know what’s going on.”

The students’ engagement is important because science education is in trouble.

While America was known for its science and technology throughout the 20th century, today the nation is falling behind in terms of producing new scientists, mathematicians, and engineers. There have been many reports over the last few decades calling for major changes in how we’re teaching our kids.

BioEYES is out to help fill that gap by giving kids the opportunity to do hands-on science. Furthermore, while the program could technically be used anywhere, they’ve made it free for schools where kids are low-income and struggling with science.

The program started back in 2002 with just two just people, Steven Farber and Jamie Shuda.

Back then, Farber was just setting up his own professional zebrafish lab when he got a surprise visit from a “take your kids to work day” group. Farber welcomed the kids, showing them around and letting them look at tiny, developing zebrafish under a microscope.

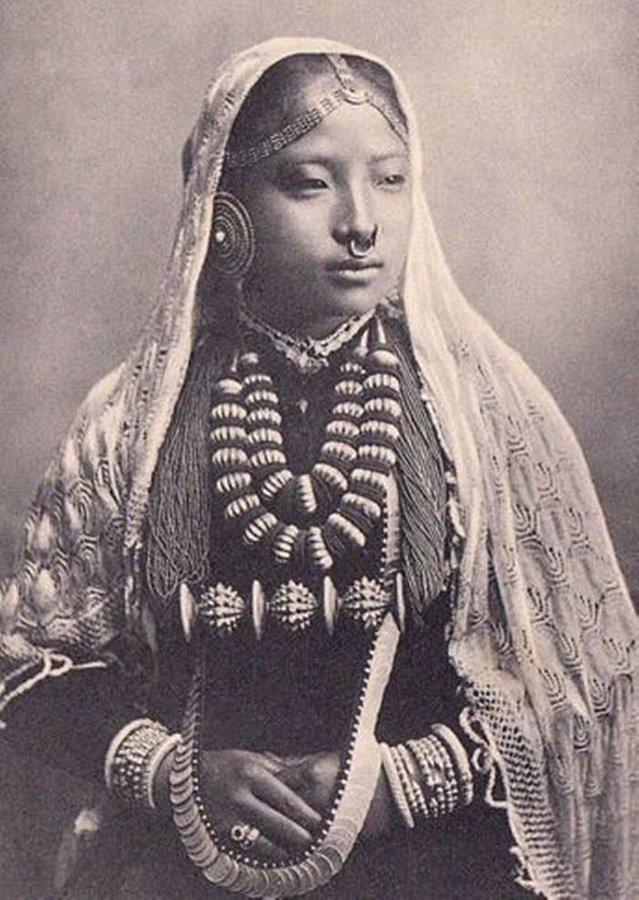

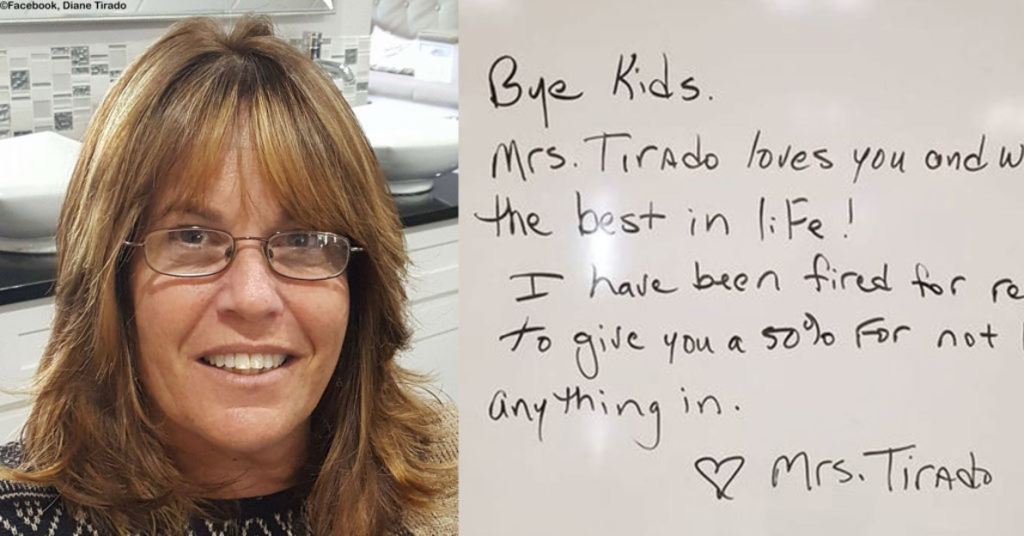

Photo from BioEYES, used with permission.

The kids were enchanted, and Farber found himself hosting more of these visits. Excited, but overwhelmed, Farber brought on Shuda, a former third-grade teacher and educator to help turn it into a program.

As they were talking, Farber and Shuda discovered they were both frustrated with the stereotypical image of a scientist as some old dude in a lab coat — something a lot of middle-school kids could not picture in their future. So they decided that, instead of just bringing a scientist into the classroom, their program would turn kids into the scientists themselves.

“Giving people the opportunity to do something they wouldn’t normally do really opens their eyes,” says Shuda. Stereotypes break down. Doors open.

Today, the BioEYES program is in more than 100 schools in the U.S. and reaches kids from second grade through high school.

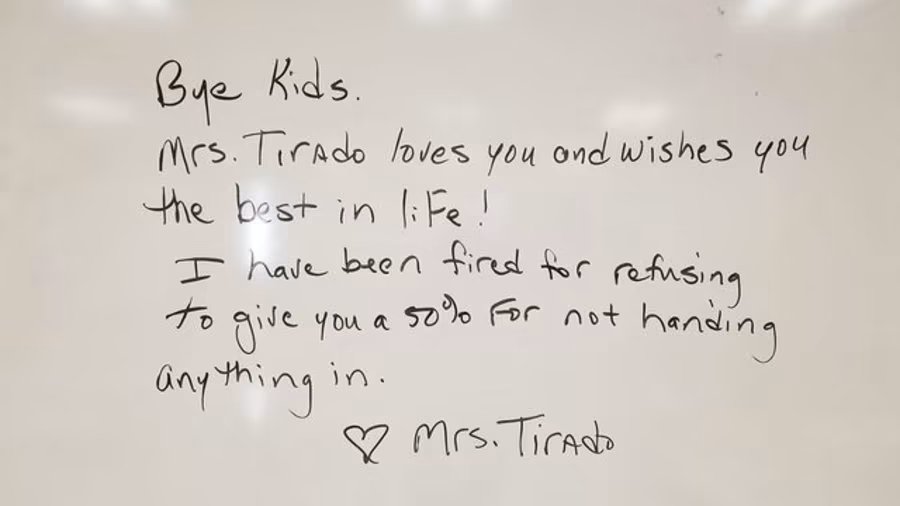

Photo from BioEYES, used with permission.

The program can be tailored for each class. Carey’s kids, for instance, are learning about genetics.

In Carey’s class, the kids get two parent fish — one with the zebrafish species’ typical silver and grey stripes and the other a colorless albino. Their question is what color will their offspring be.

For five days, the kids make hypotheses, observe the babies develop, and care for the growing embryos as if they were in a working laboratory. They can use the microscopes to watch the eggs grow from single cell to embryo to larvae. By the end of the week, the larvae are big enough that the kids can see their coloration — and find out if their hypotheses were correct.

“What makes this a really fantastic model for teaching genetics is that the kids are actually able to, with a living organism, answer a hypothesis,” Carey says. He thinks a lot of science teaching is purely didactic — look at this cell, label these organs, memorize these names. But BioEYES feels like an investigation in a real laboratory.

Photo from BioEYES, used with permission.

The first few years Carey did this, the program was actually run by one of the BioEYES outreach educators. Today, though, he’s taken the program and made it his own. He’s one of what BioEYES calls their model teachers. They use the BioEYES model and materials but tailor it to better fit their own schedules and classrooms.

“They’re the key to our success,” Shuda said.

The program seems to be working and has actually launched a few science careers.

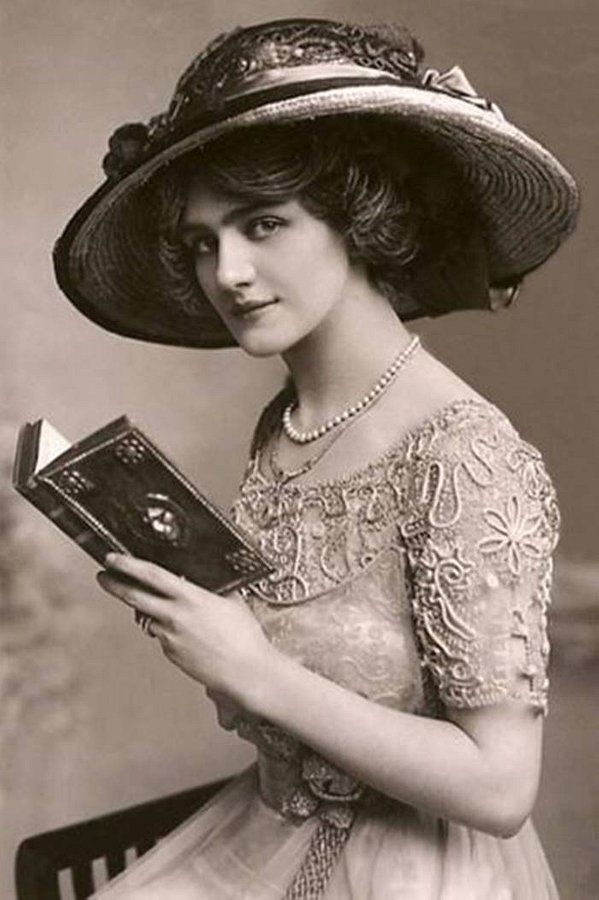

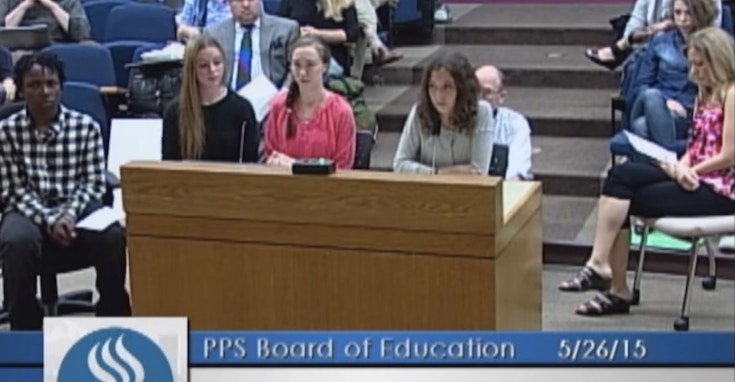

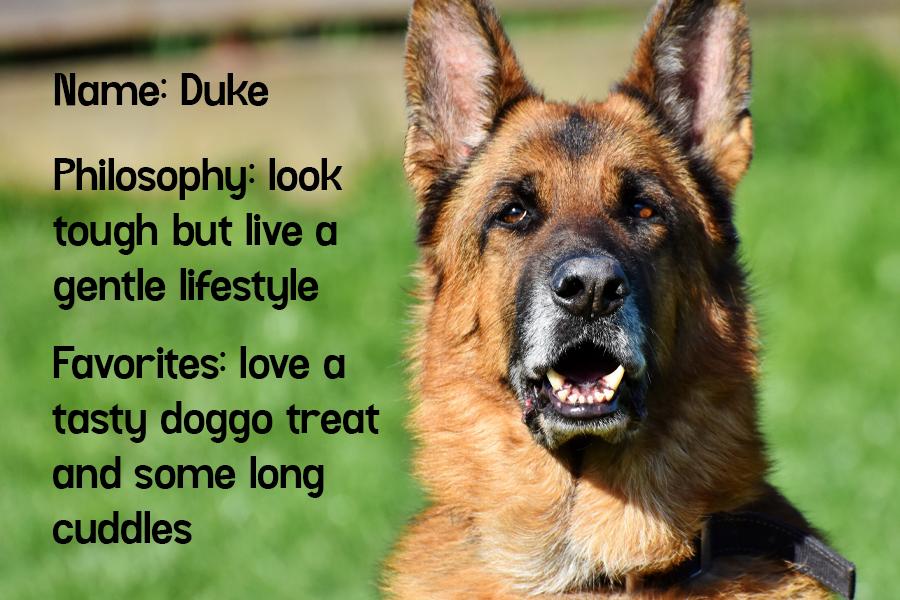

Students at Thomas Jefferson Elementary School. Image from David Schmelick and Deirdre Hammer/Johns Hopkins University.

A recent paper found that BioEYES improved test scores compared to pre-fish levels while also helping kids understand what being a scientist was actually like. Some past students have even gone on to pursue STEM careers themselves.

Fabliha Khurshan, a 21-year-old senior at the University of Pennsylvania, says she was always interested in medicine, but the program helped her understand what being in a lab was really like. Kareema Dixon, a 19-year-old sophomore engineering major at Drexel University, says, “Before BioEYES, I wanted to be a lawyer.”

Both credit the program with pushing them toward science.

It’s cool to see a program like this that both teaches and inspires kids.

“It’s something that really leaves a lasting mark,” Carey says.