Science confirms this viral 'secret' praise parenting technique is certifiably genius.

“I promise that if you do this in front of your child, their confidence will skyrocket!”

Namwila Mulwanda and her partner Zephi practice gentle parenting.

There are so many conflicting ideas about building self-confidence in children. Is there a right way? Could praise be harmful? Should everyone receive a gold star? As with many things in life, sometimes the best solution is the simplest one—hiding in plain sight, or just out of it.

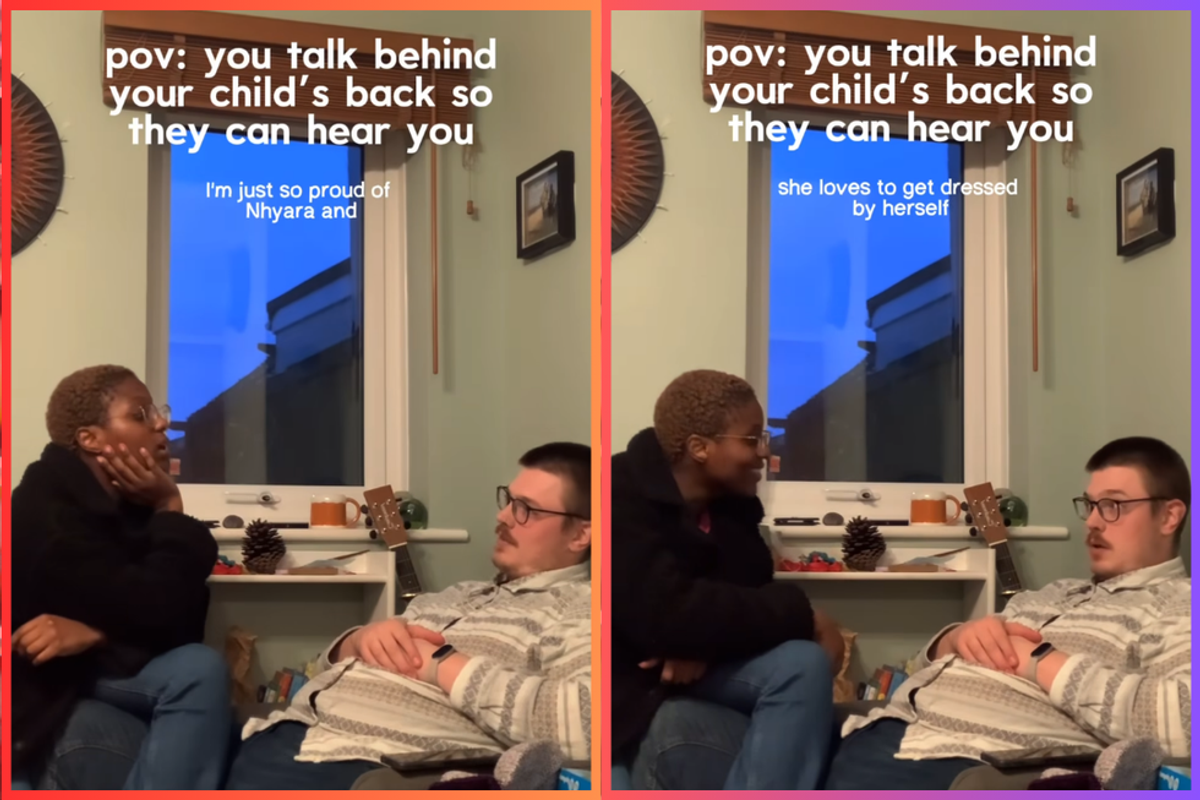

Namwila Mulwanda and her partner Zephi practice “gentle-parenting” with their daughter, Nhyara. Shared in a video on Instagram, one of their techniques is talking about Nhyara when she's within earshot but out of sight. These aren't your typical behind-closed-doors parent conversations—no venting about daily frustrations or sharing complaints they'd never say to her face. Instead, they create intentional moments of celebration, offering genuine praise and heartfelt affirmation.

In a viral Instagram post that's garnered over one million likes, Mulwanda writes, “POV: You talk behind your child's back so they can hear you.” Self-described as a “passionate mother, content creator, and small business owner,” Mulwanda naturally overflows with ideas: she writes a Substack, She Who Blooms, which is about “blooming in our own time, in our own way.” She also runs Rooted, a shop where she “carefully curates products that embody the essence of growth, empowerment, and staying rooted in one's true self.”

In the video, Mulwanda and her partner sit in a quiet corner, chatting about their daughter Nhyara while occasionally peeking around to see if she's listening—which she is. With her within earshot but not directly part of the conversation, they discuss their daughter:

“I'm just so proud of her and the things she does,” her mom starts.

“She works on her reading, like that difficult word that she took the time to really sound out,” adds her dad. They go on to applaud her independence (“She's always telling me, 'Daddy, I want to brush my teeth on my own,'” says Zephi), before concluding that she's amazing.

“She's amazing,” says Mulwanda. “So, so, so amazing,” Zephi responds.

People in the comments were obviously here for it. Parents shared their own versions of this technique, including one who wrote, “As a solo mom, I pretend to make phone calls to a family member and do this.”

Another parent shared a powerful example:

“My son used to be scared of climbing down the stairs. So, my husband said loudly, 'He's very brave! He has shown a lot of courage lately.' The next day, when we tried carrying him down the stairs, he said, 'Nope, I have a lot of courage in me.'”

Others reflected on their own childhoods. One commenter wrote, “No exaggeration, I'd be an entirely different person had my parents been like this with me.”

“Stop, I was just thinking last night, 'When I have kids, I'm going to have loud conversations with my future husband about how much I love our children and how proud I am of them,'” another enthusiastically shared.

Research indicates that indirect praise has a stronger psychological impact than direct praise, particularly in young children.

“This is such a powerful way of reinforcing positive behavior,” explains parenting influencer Cara Nicole, who also went viral for her unique approach to parenting. “There's something special about overhearing others talk about you—you know they're being genuine because they're not saying it directly to you.”

- YouTube www.youtube.com

This effectiveness stems from children's innate understanding that conversations between adults tend to be more honest than parent-child interactions. From an early age, children recognize that direct conversations with parents often have an intentional, behavior-shaping purpose. In contrast, overheard praise feels authentic and spontaneous, rather than an attempt to influence the child's self-image.

These techniques work best when praise focuses on effort and process rather than innate qualities. Take Nhyara's dad's comment: “She works on her reading, like that difficult word that she took the time to really sound out.”

Yet, it's crucial to keep praise realistic and measured. Avoid overzealous claims about future achievements, like acing every spelling test for the rest of her life. Children have keen intuition; if they sense insincerity, the strategy can backfire, damaging their trust in parents. Similarly, over-inflated praise—like declaring “incredible” performance for average effort—can burden children with unrealistic expectations.

Keep it simple. A casual remark like, “I noticed how carefully Maya put away her toys without being asked. That was so nice. It really helped keep the house clean.”

The viral response to Mulwanda's video demonstrates the power of gentle parenting combined with thoughtful, specific praise. It's heartening to see modern parents sharing their diverse approaches to showing their children love. For many commenters who didn't experience this kind of upbringing, these conversations offer a path to healing. As Mulwanda eloquently states in her pinned comment:

“To those of you who only heard negative as a child, you were never the problem. You were a child, and you didn’t deserve the experience you had. Your presence on this earth is a blessing, and the fact that you show up every single day is proof of just how amazing you are. You are brave, you are beautiful (you too, boys), and you deserve the world and more.

If any of you feel emotions rising up, close your eyes, hug your inner child, and remind them that you’re there.” - Namwila Mulwanda

Interestingly, parenting coach Dr. Chelsey dived into the ideal frequency of giving a child praise, especially if you're wanting to encourage specific behavior. that number was at a whopping 100 times a day. Holy moly! For neurodivergent kiddos, that number increases significantly. While that much praise might seem impossible, Dr. Chelsey also breaks down how to make it more doable with that she calls "sportscaster praise” below:

Bottom line: children start building their self-image through absorbing their parent's view of them. Let's make sure those building blocks are strong and steady.

This article originally appeared in June.