6 unexpected and life-changing things I learned while living in a monastery.

One man explains what it's really like to live in a monastery.

In 2010, a medication-resistant form of epilepsy terrorized me.

Facing the prospect of a near-permanent state of illness, I longed for respite. I needed something — anything — to calm me down.

I had been reading the works of Christian and Buddhist monks for years, but I had never actually visited a monastery.

So I decided in a moment of panic: Why not take a retreat to a monastic community?

I knew there were some monasteries in the U.S. that invited guests to visit, so I contacted a monastery I had been following and arranged for a five-day retreat.

The view from the retreat center at the monastery. Photo by Tim Lawrence, used with permission.

During my first visit, I found myself surrounded by some of the most loving men I had ever encountered. To my delight, many of my epileptic symptoms subsided during my stay, too. I wasn’t cured by any means, but the lack of stress and centering nature of the monastery seemed to temporarily clothe me in a blanket of inner peace that I desperately needed.

And after the first retreat, I longed to have the chance to experience what this monastic life was truly like for more than a few days. After several more short retreats, I came across a program at a monastery in Boston that allowed just that.

With a handful of young people, I prepared to live alongside monks for nine months.

When I walked into the monastery on that first day, I was nervous. I had no idea what to expect. But by the time I left, I couldn't imagine my life without that time spent at the monastery.

The experience both frustrated me and blew me away: It forced me to confront my fears, examine my motivations, and take stock of how I really lived my life in a way that no other experience ever had.

Here are a few of the things I learned:

1. Living in silence is really powerful.

After the last service of the day, called the Greater Silence, complete silence was observed for 12 hours until the morning. Although the community members did speak during the day, both the monks and residents were encouraged to keep our speaking to a minimum in order to preserve an atmosphere of mindfulness and refuge for both the community and its guests.

Unexpectedly, this quiet is what I have missed most since leaving.

At the monastery, I was more present in the moment. When my dear friend Amelia lost a loved one, I found myself far more available to her. When my friend Daniel and I found ourselves with the opportunity to talk for extended periods of time during breaks at the monastery, we spoke to each other more slowly, and with far more honesty, than we normally would in the outside world.

What I learned is that silence forced me to change because I was actually living differently. I became more confident because I was less inclined to seek out the approval of others through empty words. I also chose my words carefully when I did speak, and I spoke with more authority.

2. I felt less lonely than I thought I would.

I initially worried that being cloistered at the monastery would cause me to be intensely lonely. However, although I was disconnected from the outside world for much of the time, I felt less lonely than I had in the "real world."

Why? I think it’s because the monastic community nourished me and loved me with abandon. The fact that I felt so grounded much of the time was a testament to the power of people actively connecting with one another, with intention.

3. Living minimally was freeing.

I had been living as a nomad with few possessions before I went to the monastery, but I had never embraced anything resembling a vow of poverty. And although I wasn’t obligated to partake in a formal vow of poverty, I still chose to live as simply as possible while I was there.

When you live with few possessions in a sparse, basic cell, your need for "things" dissipates rapidly. You become more adaptable, and you find that rather than trying to attain more, you learn to want what you already have. I found this to be liberating and beautiful.

4. Giving up some personal freedom for the sake of community wasn’t stifling.

In our rampantly individualistic culture, it’s easy to prize personal freedom above all else. Yet when you live in community, the needs of the community are placed above the desires of the individual. This was incredibly challenging and freeing for me because I was often asked to forego some of my own desires for the sake of the community.

I couldn’t dash off whenever I wanted, and I was expected to be present for all community activities, so I had to become willing to sacrifice some of my own selfishness in order to serve my peers. I was a part of something larger than myself, and that meant that I had to shed some of my self-absorption for the sake of others every single day.

5. My appreciation of time shifted.

The writer Sarah Manguso has said, "Time isn’t made of moments; it contains moments. There is more to it than moments."

I never understood this until I saw it in the monastery. In monastic life there’s always a "next thing" — another activity to devote one’s focus to over and over again. Whether I was chanting or eating a meal, I was expected to be fully present there, and then to let it go once it was over. Because the days were so structured, I was forced to become one with the moments I was experiencing; the "next thing" always demanded my full attention.

Time is taken more seriously as a resource in a monastery, which is something I took with me after I left.

6. Most of the spiritual "myths" about monasteries aren’t true.

I quickly found that many of my assumptions about monastic life were wrong. Contrary to what some people might think, living with monks isn’t a series of mountaintop experiences where you’re free to deepen your spirituality unimpeded by the difficulties of daily life.

In fact, the grind of life can be even more present in a monastery because everyone is expected to contribute in a series of repetitive duties. Monastic life is rhythmical, and monks hold that rhythm sacred. All services, meals, and chores are held at specific times with only occasional deviation.

To my surprise, this rhythm served as a great catalyst for personal transformation, though. In monastic life, I was taught not to separate "spiritual" time from "normal" time but to explore the vagaries of my spiritual life precisely when I was doing mundane, trivial work. This turned out to not only be enriching but life-changing.

My moments of greatest peace and transcendence came when I was cleaning out a kitchen or raking leaves or sitting in a chapel, alone, reflecting on my infinitesimal place in the world.

I learned to feel adequate in what could easily be described as an inadequate setting.

The transition out of the monastery wasn’t easy.

I left early because of my epilepsy; the long 16-hour days took a toll on me. I remember going to New York shortly after leaving and feeling a strong sense of panic: I was panicked because everyone else seemed so panicked. Society seemed strained to me, and I had a difficult time adjusting to "civilian life" again.

It took a few months to find my footing and to retain my monastic identity in a world that seems to place so much value on what monasticism has little need for — namely: status, wealth, and success.

But shortly before I left, the wisest monk I know told me something that made me weep, something that I will take with me everywhere: He said that I was a walking miracle.

This stopped me in my tracks because his words showed that he had chosen to love me as unconditionally as an imperfect, fragile human is capable of. This is a rare thing.

Me with the superior at the monastery. Photo via Tim Lawrence, used with permission.

My experience in the monastery revealed more of our human ability to love and be loved than I've ever seen before.

I was forced to evaluate how I related to the world not just for a day, but continually. I didn’t rise above all of my weaknesses or transform my entire life, but that was OK. I am deeply indebted to my fellow brothers and residents for caring for me so thoroughly.

In the end, I found the courage to experience being alive differently. The change was subtle yet profound, and I will carry that with me forever.

A Baby Boomer couple.via

A Baby Boomer couple.via  A Baby Boomer couple.via

A Baby Boomer couple.via

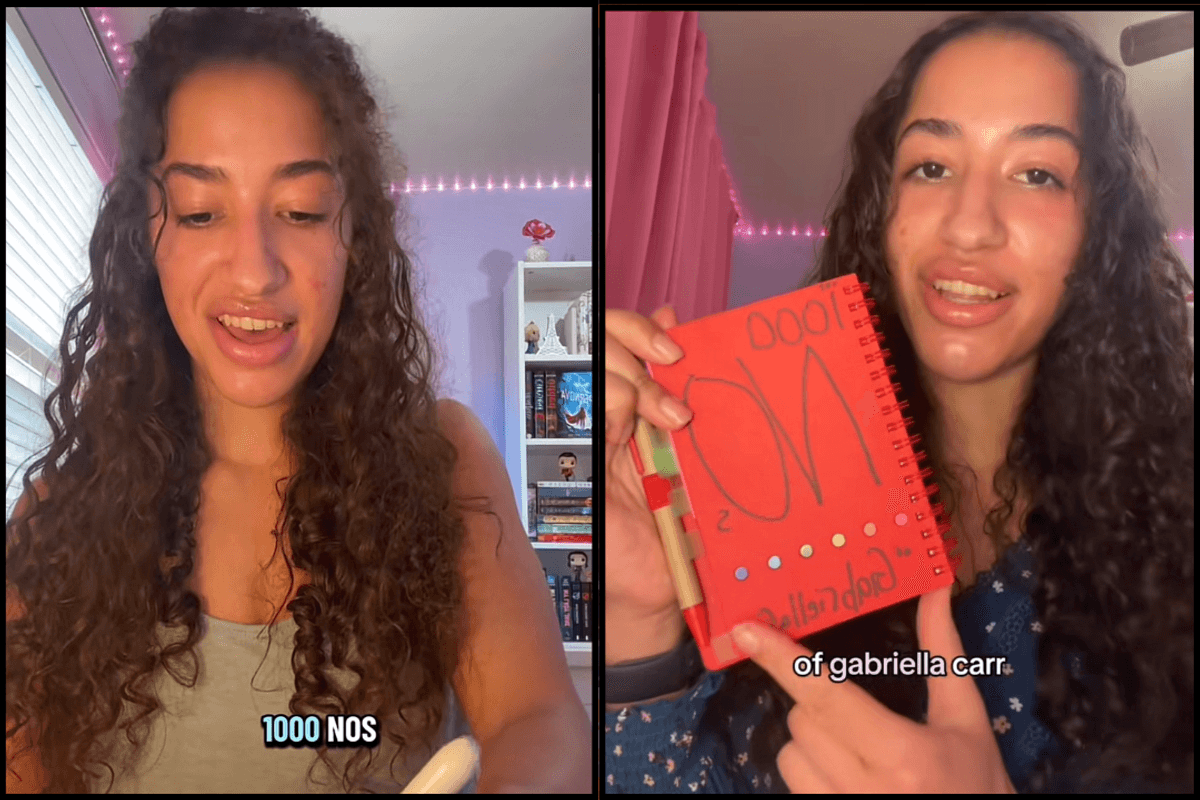

This is where Gabrielle tracks her rejection journey.

This is where Gabrielle tracks her rejection journey. Social rejection feels just like physical pain to the brain.

Social rejection feels just like physical pain to the brain. Asking questions can be a form of bravery.

Asking questions can be a form of bravery.

Woman working, productively.

Woman working, productively.

An exhausted mom and her baby.

An exhausted mom and her baby. A mom yawns while feeding her baby.

A mom yawns while feeding her baby.