The real-life Christopher Robin only accepted a tiny royalty from Disney and it's still changing lives

Pooh would be proud.

The real-life Christopher Robin accepted a tiny payment from Disney that's still changing lives.

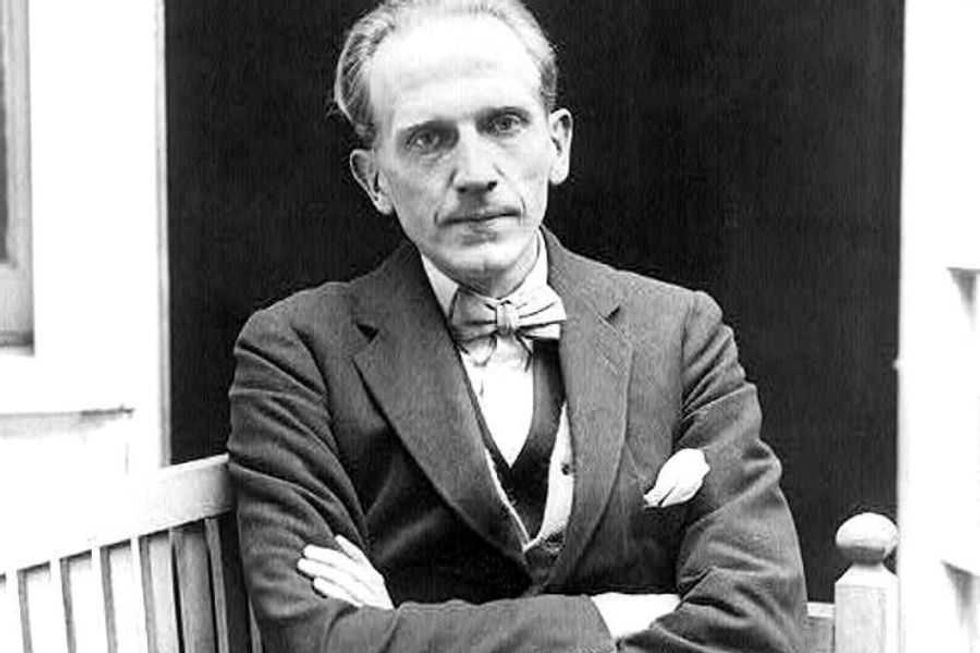

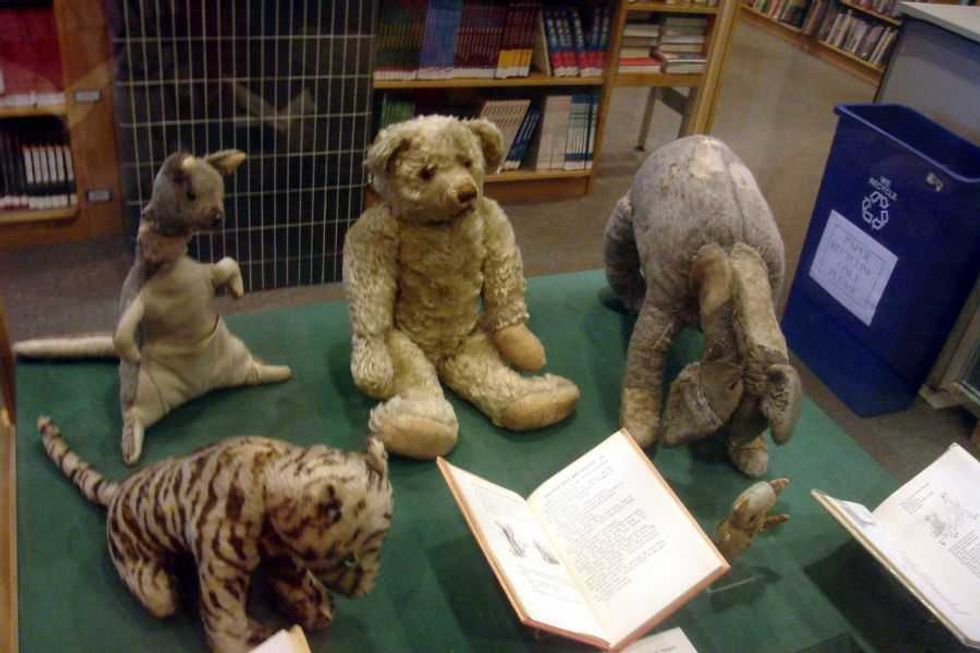

Winnie the Pooh is a timeless children's classic that transcends generations. But younger audiences may not know that the bear's human friend, Christopher Robin, was based on an actual child by the same name. Author A.A. Milne wrote the children's book Winnie the Pooh as a collection of stories in 1926 about a boy and his imaginary friends, who were all based on his son's stuffed toys, except Owl and Rabbit (whom the elder Milne made up).

Christopher Robin Milne was thrilled to be a character in his father's popular book when he was six, but once he reached the age of 10, things took a turn. The young Milne wanted to be seen as separate from the imaginative little boy in the book, but the world wouldn't let him, which led to deep resentment. His complicated relationship with the chubby little cubby fueled his estrangement from his famous father and resulted in him not wanting the royalties later in life.

The estrangement with his family ran deep, extending far beyond his father for decades. According to a recent interview on Nostalgia Tonight, Gyles Brandreth, a friend of the late Christopher Robin, explains that the younger Milne's perception began to change about being immortalized in a children's book after he went to boarding school.

"Then, when he went away to boarding school people began to tease him. He was Christopher Robin, and then when he joined the army and after the Army and after University, and he was in his life, trying to get a job. He would go to interviews and people would say, 'Oh, your name's Milne. Are you by any chance related to the famous writer?' or 'Your initials are CRM. You must be Christopher Robin. How's Winnie the Pooh?' and that infuriated him," Brandreth told Nostalgia Tonight. "He got to the stage where he really couldn't stand it. And in fact, he accused his father of building his reputation by standing on a small boy's shoulders. And the father and son eventually fell out. And there, the family became a divided family."

Christopher Robin's relationship became more strained with his parents when he decided to marry his first cousin, Lesley de Selincourt. While the two didn't know each other before dating, as their families were estranged, it still prompted intense criticism and more of a rift. The couple left London to live in the country away from everyone else, including the overshadowing presence of an imaginary bear obsessed with honey.

The young couple had no interest in the elder Milne's money from the books, so when A.A. Milne died in 1956, Christopher Robin wanted nothing to do with Pooh Properties Trust set up by his father. Christopher Robin managed the trust and was one of the original five recipients. While he handled all of the royalties, he didn't use any of it, including after Disney began paying royalties into the trust after acquiring licensing rights from Stephen Slesinger Inc., the company of an American literary agent Milne signed with. Slesinger purchased the merchandising rights for $1,000 in 1930. By 1961, nearly 10 years after Slessinger died, his wife sold the rights to Disney.

The animation giant agreed to pay a portion of royalties to Stephen Slesinger Inc., while still paying royalties to Pooh Properties Trust. Pooh Properties didn't sell the literary rights to Disney at the time, though Christopher Robin's relationship with the bear remained complicated. All while dealing with business around the trust he didn't want, the younger Milne and his wife were caring for their daughter, who was born with cerebral palsy. In 1980, the reluctant heir sold a portion of the estate to create a separate trust to care for his daughter, Clare.

In 2001, Pooh Properties Trust agreed to sell the literary rights to Disney for $350 million. Though Christopher Robin sold his portion of the estate and no longer received royalties from Disney, the portion he set aside for Clare continues to provide today. The Clare Milne Trust supports people living with disabilities by providing charities that serve disabled individuals who live in Devon and Cornwall, England.