Unless you're a child, New York City resident, or UPS driver, chances are you've made a left turn in your car at least once this week.

Chances are, you didn't think too much about how you did it or why you did it that way.

You just clicked on your turn signal...

...and turned left.

The New York State Department of Motor Vehicles instructs drivers to "try to use the left side of the intersection to help make sure that you do not interfere with traffic headed toward you that wants to turn left," as depicted in this thrilling official state government animation:

Slick, smooth, and — in theory — as safe as can be.

Your Drivers Ed teacher would give you full marks for that beautifully executed maneuver.

Your great-grandfather, on the other hand, would be horrified.

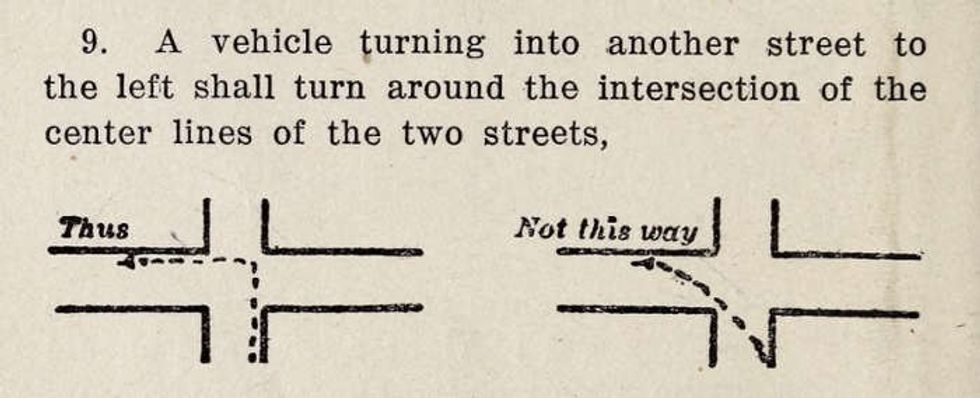

Before 1930, if you wanted to hang a left in a medium-to-large American city, you most likely did it like so:

Instead of proceeding in an arc across the intersection, drivers carefully proceeded straight out across the center line of the road they were turning on and turned at a near-90-degree angle.

Often, there was a giant cast-iron tower in the middle of the road to make sure drivers didn't cheat.

These old-timey driving rules transformed busy intersections into informal roundabouts, forcing cars to slow down so that they didn't hit pedestrians from behind.

Or so that, if they did, it wasn't too painful.

"There was a real struggle first of all by the urban majority against cars taking over the street, and then a sort of counter-struggle by the people who wanted to sell cars," explains Peter Norton, Associate Professor of History at the University of Virginia and author of "Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City."

Norton posted the vintage left-turn instructional image, originally published in a 1919 St. Louis drivers' manual — to Facebook on July 9. While regulations were laxer in suburban and rural areas, he explains, the sharp right-angle turn was standard in nearly every major American city through the late '20s.

“That left turn rule was a real nuisance if you were a driver, but it was a real blessing if you were a walker," he says.

Early traffic laws focused mainly on protecting pedestrians from cars, which were considered a public menace.

For a few blissful decades after the automobile was invented, the question of how to prevent drivers from mowing down all of midtown every day was front-of-mind for many urban policymakers.

Pedestrians, Norton explains, accounted for a whopping 75 percent of road deaths back then. City-dwellers who, unlike their country counterparts, often walked on streets were predictably pretty pissed about that.

In 1903, New York City implemented one of the first traffic ordinances in the country, which codified the right-angle left. Initially, no one knew or cared, so the following year, the city stuck a bunch of big metal towers in the middle of the intersections, which pretty well spelled things out.

Some cities installed unmanned versions, dubbed "silent policemen," which instructed motorists to "keep to the right."

Drivers finally got the message, and soon, the right-angle left turn spread to virtually every city in America.

Things were pretty good for pedestrians — for a while.

In the 1920s, that changed when automobile groups banded together to impose a shiny new left turn on America's drivers.

According to Norton, a sales slump in 1922 to 1923 convinced many automakers that they'd maxed out their market potential in big cities. Few people, it seemed, wanted to drive in urban America. Parking spaces were nonexistent, traffic was slow-moving, and turning left was a time-consuming hassle. Most importantly, there were too many people on the road.

In order to attract more customers, they needed to make cities more hospitable to cars.

Thus began an effort to shift the presumed owner of the road, "from the pedestrian to the driver."

"It was a multi-front campaign," Norton says.

The lobbying started with local groups — taxi cab companies, truck fleet operators, car dealers associations — and eventually grew to include groups like the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce, which represented most major U.S. automakers.

Car advocates initially worked to take control of the traffic engineering profession. The first national firm, the Albert Erskine Bureau for Street Traffic Research, was founded in 1925 at Harvard University, with funds from Studebaker to make recommendations to cities on how to design streets.

Driving fast, they argued, was not inherently dangerous, but something that could be safe with proper road design.

Drivers weren't responsible for road collisions. Pedestrians were.

Therefore, impeding traffic flow to give walkers an advantage at the expense of motor vehicle operators, they argued, is wasteful, inconvenient, and inefficient.

Out went the right-angle left turn.

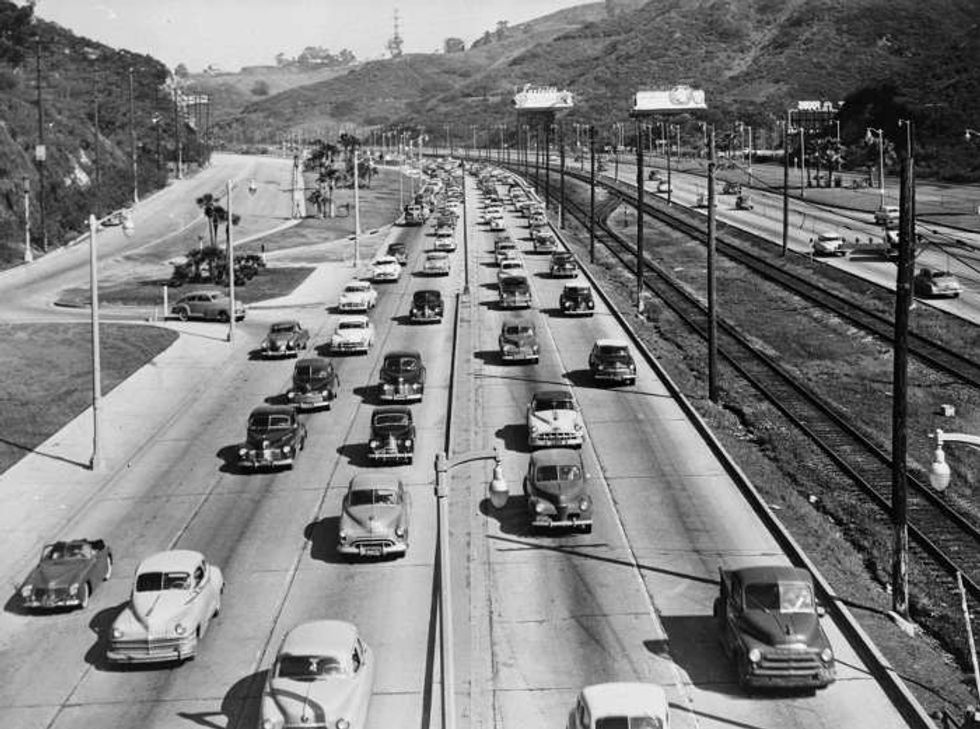

Industry-led automotive interest groups began producing off-the-shelf traffic ordinances modeled on Los Angeles' driver-friendly 1925 traffic code, including our modern-day left turn, which was adopted by municipalities across the country.

The towering silent policemen were replaced by dome-shaped bumps called "traffic mushrooms," which could be driven over.

Eventually the bumps were removed altogether. Barriers and double yellow lines that ended at the beginning of an intersection encouraged drivers to begin their left turns immediately.

The old way of hanging a left was mostly extinct by 1930 as the new, auto-friendly ordinances proved durable.

So ... is the new left turn better?

Yes. Also, no.

It's complicated.

The shift to a "car-dominant status quo," Norton explains, wasn't completely manufactured — nor entirely negative.

As more Americans bought cars, public opinion of who should run the road really did change. The current left turn model is better and more efficient for drivers — who have to cross fewer lanes of traffic — and streets are less chaotic than they were in the early part of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, pedestrian deaths have declined markedly over the years. While walkers made up 75% of all traffic fatalities in the 1920s in some cities, by 2015, just over 5,000 pedestrians were killed by cars on the street, roughly 15% of all vehicle-related deaths.

There's a catch, of course.

While no one factor fully accounts for the decrease in pedestrian deaths, Norton believes the industry's success in making roadways completely inhospitable to walkers helps explain the trend.

Simply put, fewer people are hit because fewer people are crossing the street (or walking at all). The explosion of auto-friendly city ordinances — which, among other things, allowed drivers to make faster, more aggressive left turns — pushed people off the sidewalks and into their own vehicles.

When that happened, the nature of traffic accidents changed.

"Very often, a person killed in a car in 1960 would have been a pedestrian a couple of decades earlier," Norton says.

We still live with that car-dominant model and the challenges that arise from it. Urban design that prioritizes drivers over walkers contributes to sprawl and, ultimately, to carbon emissions. A system engineered to facilitate auto movement also allows motor vehicle operators to avoid responsibility for sharing the street in subtle ways. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists three tips to prevent injuries and deaths from car-human collisions — all for pedestrians, including "carrying a flashlight when walking," and "wearing retro-reflective clothing."

A Minneapolis Star-Tribune analysis found that, of over 3,000 total collisions with pedestrians (including 95 fatalities) in the Twin Cities area between 2010 and 2014, only 28 drivers were charged and convicted a crime — mostly misdemeanors.

Norton says he's encouraged, however, by recent efforts to reclaim city streets and make them safe for walkers.

That includes a push by groups like Transportation Alternatives to install pedestrian plazas and bike lanes and to promote bus rapid transit. It also includes Vision Zero, a safety initiative in cities across America, which aims to end traffic fatalities by upgrading road signage, lowering speed limits, and installing more traffic circles, among other things.

As a historian, Norton hopes Americans come to understand that the way we behave on the road isn't static or, necessarily, what we naturally prefer. Often, he explains, it results from hundreds of conscious decisions made over decades.

"We're surrounded by assumptions that are affecting our choices, and we don't know where those assumptions come from because we don't know our own history," he says.

Even something as mindless as hanging a left.

This article was originally published on July 14, 2017.

- Why is building trains so expensive in America? - Upworthy ›

- Lefties share man's delight over left-handed scissors - Upworthy ›

- Food we still eat from 100 years ago - Upworthy ›

- Street artist saved lives and cut traffic after vandalizing notorious Los Angeles highway sign - Upworthy ›

- Man in India declared dead until his ambulance hit a speed bump that saved his life - Upworthy ›

Teens hanging out in a living room.via

Teens hanging out in a living room.via  Teenagers eating pizza.via

Teenagers eating pizza.via  Teenagers eating pizza.via

Teenagers eating pizza.via

Princess Odette Girl GIF by The Swan Princess

Princess Odette Girl GIF by The Swan Princess  Rose GIF

Rose GIF  sailor moon GIF

sailor moon GIF  river phoenix 80s GIF

river phoenix 80s GIF

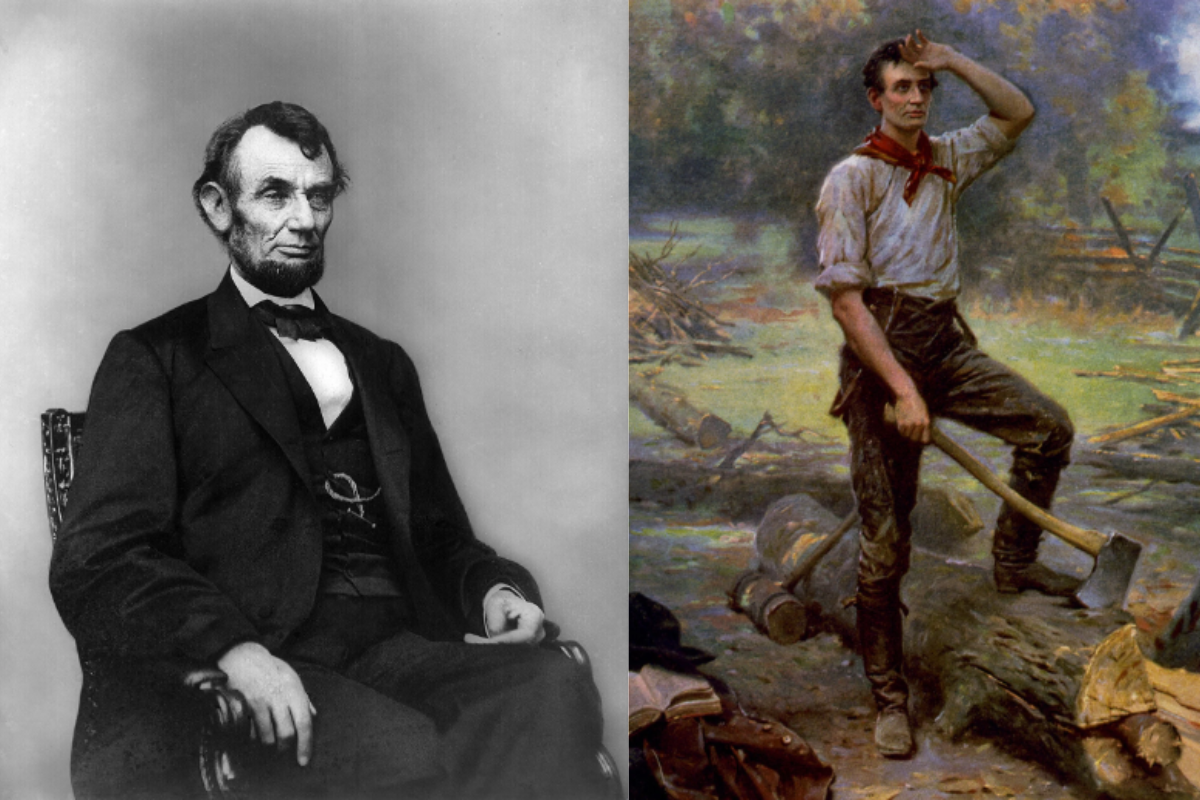

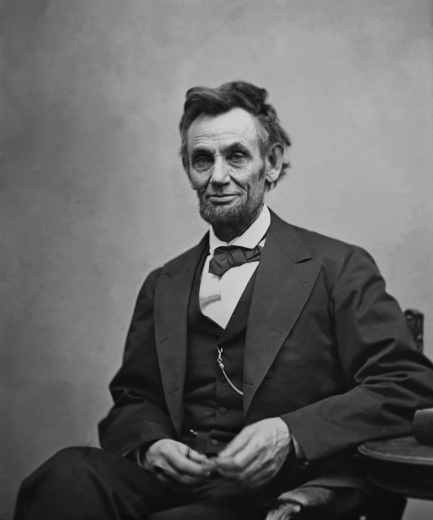

Abraham Lincoln portrait by Alexander Gardner in 1865.

Abraham Lincoln portrait by Alexander Gardner in 1865.

Student smiling in a classroom, working on a laptop.

Student smiling in a classroom, working on a laptop. Students focused and ready to learn in the classroom.

Students focused and ready to learn in the classroom.