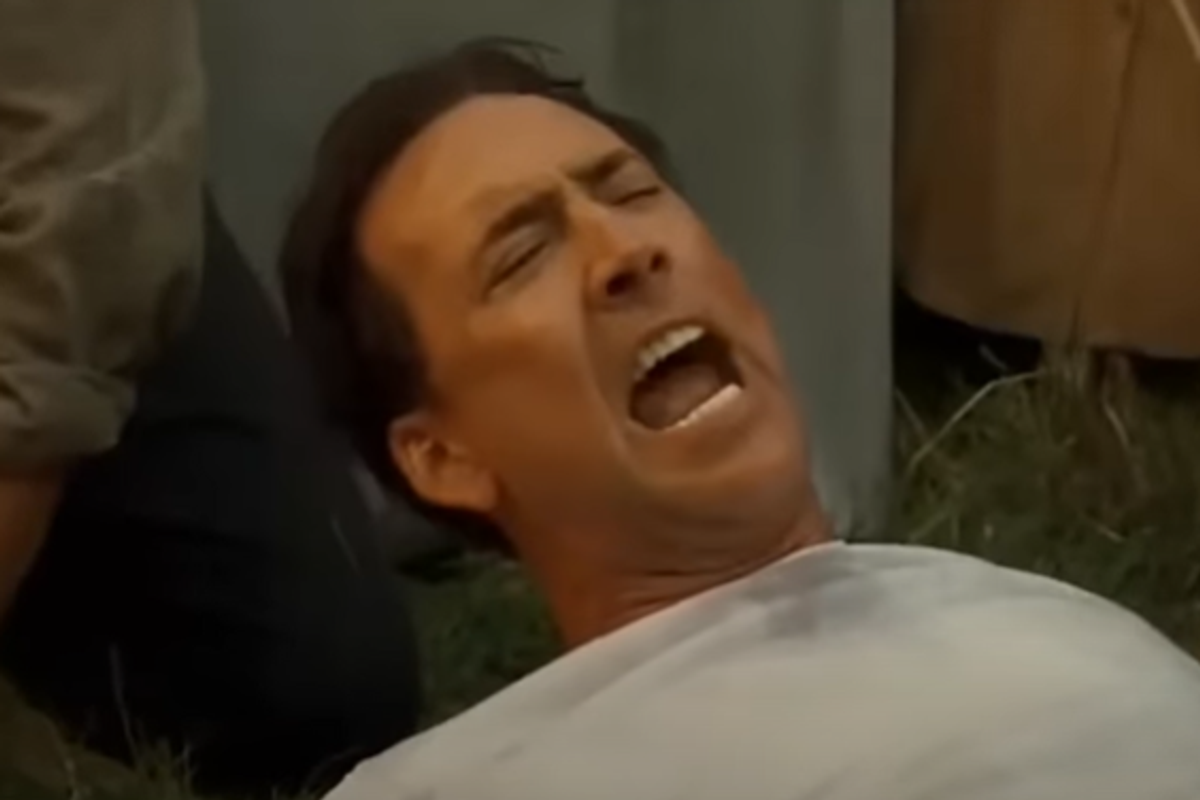

Nicolas Cage freaking out in over 40 perfectly edited scenes is a great stress reliever

Cage's meltdowns are cathartic.

Nicolas Cage freaking out.

Nicolas Cage is one of the most iconic American actors because he has a style all his own. The star of “Face/Off,” “National Treasure” and last year's sleeper hit, “Longlegs,” is known for having an intense screen presence where he always seems to be on the brink of losing it. And quite often, he does.

Cage has no problem admitting his tendency to take things to the extreme on screen.

“You can go as big as you want as long as it’s honest, as long as you’re still putting the emotional content behind it,” Cage told “In the Envelope: The Actor’s Podcast.” “When people say, ‘Well, that’s over the top,’ I say, ‘Well, you tell me what the top is, and I’ll let you know whether or not I’m over it.’ I’m working on something, and I’m trying to find something which I think is exciting."

A YouTuber named MonkeyGrip100 cut together over 40 scenes where Cage absolutely loses it and the video is strangely cathartic. There’s something about watching Cage howl, scream, kick, wave his arms and yell at the sky that can make any hard day feel a bit easier.

The video is like a session of second-hand primal scream therapy.

WARNING: Video contains foul language and violence.

- YouTubeyoutu.be

“Well, you gotta admit he definitely goes 110% in all of his roles and no one can ever take that away from him,” one commenter on the YouTube video wrote. “Despite all my rage, I'm still just Nicholas Cage,” another added, paraphrasing “Bullet with Butterfly Wings” by The Smashing Pumpkins.

If you watched the 4-plus minute video of Cage venting, screaming, moaning and going through horrifying personal pain and came out of it feeling better for it, don’t worry; you’re not a sadist. In fact, according to psychologists, it’s completely healthy.

According to Lysn psychologist Nancy Sokarno, watching sad or depressing movies when we feel bad makes us feel better.

“To simplify that a little, consuming depressing content can actually make you feel good [because] of [increased] endorphins. Who would have thought! So, when we’re wanting to consume [traumatic] content when we’re in a low mood, our brains are essentially chasing those feel good endorphins,” Sokarno told Refinery29.

According to Sokarno, we get the same feeling when we listen to depressing music. “When we listen to sad music, it tricks the brain into releasing a hormone called prolactin, which is associated with helping to curb grief,” Sokarno continues. "So, in the absence of a traumatic event, the body is left with this pleasurable mix of opiates which produces feelings of calmness [and] helps to counteract mental pain.”

Cage has been criticized throughout his career for being a little over the top with his acting, but the joke isn’t lost on him. He knows what he’s doing. The great thing for all of us is that Cage has suffered both on screen and off to give us a feeling of catharsis. That’s probably why, even though he’s had some significant ups and downs in his career, we just can’t get enough of him. We need him to feel better about ourselves. Thanks, Nic.

- My father trafficked me throughout my entire childhood. It looked nothing like people think. ›

- Why Is Bill Nye Acting Like A Lunatic? Because He Doesn't Want To Get Blown Up, That's Why. ›

- Nic Cage delivered the most wholesome answers during an extremely rare fan Q&A ›

- Mom reveals what's in her 12-year-old son's locker and it keeps getting weirder - Upworthy ›