A Black Jewish woman shared her unique perspective on Nick Cannon's anti-semitic comments

Musical artist Nick Cannon was fired from Viacom this week after the release of a podcast in which he made anti-semitic comments. According to the New York Times, the podcast was an interview with Richard Griffin (also known as Professor Griff), who was kicked out of the band Public Enemy after blaming Jews for most of the wickedness in the world in a 1989 interview. "The Jews are wicked. And we can prove this," he told the Washington Times. Cannon told Griffin he'd been "speaking facts" and also praised Louis Farrakhan, who has been known to make anti-semitic comments.

In addition, Cannon referenced a conspiracy theory that the media is all controlled by wealthy Jewish families. "I find myself wanting to debate this idea and it gets real wishy and washy and unclear for me when we give so much power to the 'theys,'" he said, "and 'theys' then turn into illuminati, the Zionists, the Rothschilds." He also said that Black people are the true Semitic people. "You can't be anti-Semitic when we are the Semitic people," he said. "That's our birthright. So if that's truly our birthright, there's no hate involved."

At first, despite the backlash, Nick Cannon refused to apologize for this remarks. Responses to his firing ranged widely across the internet, with some calling him out as a bigot and some praising him for what they saw as "free speech."

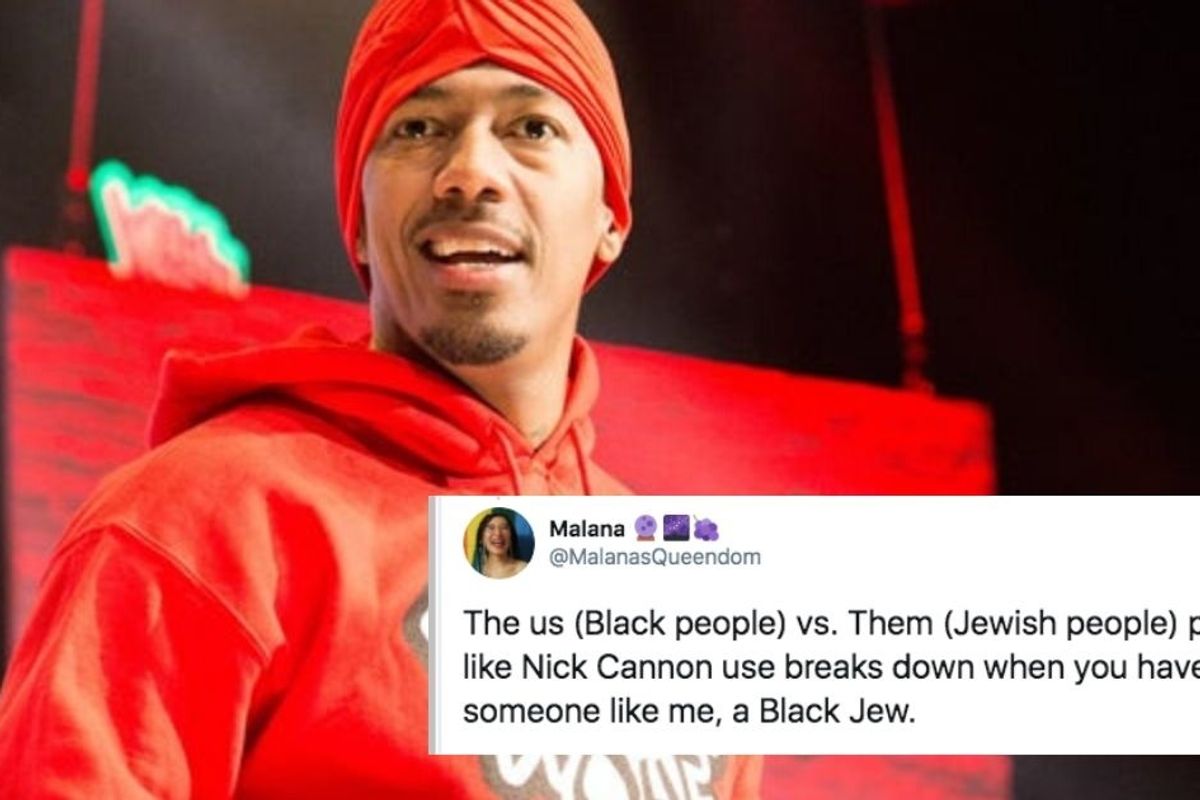

But one woman on Twitter, who happens to be Black and Jewish, took the opportunity to explain exactly why his comments were so problematic. Speaking as "your Black & Jewish educational fairy godmother," Malana wrote:

"My partner and I were just discussing how a lot of Black people don't have the education around anti-Semitism to fully get why Nick Cannon's rant was messed up. So let me be your Black & Jewish educational fairy godmother.

First, that Rothschild bank theory. That ain't real. Many Jewish people in Europe were forced to work in banking because of laws restricting them from entering other types of work. This is where the stereotypes of stingy, money grubbing, banking, etc. Come from.

But it was the racist/anti-Semitic structures that pushed Jewish people into that system in the first place. This is similar to calling Black people Welfare Queens - a system was created that locked people into place and a stereotype was invented around it.

One old-timey Jewish family being rich doesn't mean there's a conspiracy theory. It's like wealth inequality has existed for generations! *gasp* If you want to know who runs the banks google Bank of America and Chase (hint- they're very white and very not Jewish).

Now as far as Nick calling Jewish people savages, I hope it's pretty obvious why this is anti-Semitic. But in case it's not, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Untermensch

Then Nick's whole original semite thing...ugh... there's so much wrong with it. So the idea is that Jews stole Black people's identity as the 'true' people of israel. This means that Jewish people are to be blamed for all the racism Black people experience.

You see this a lot in Farrakhan's rhetoric. Taken to the extreme, you'd have [sic] to exterminate racism you'd have to exterminate Jewish people so Black people can reclaim their spot as the 'chosen people.'

Farrakhan and other Black supremacists use Jewish people as a boogeyman and scapegoat to push their own agenda and cult of personality. There can be no end to racism without an end to anti-semitism

The us (Black people) vs. Them (Jewish people) people like Nick Cannon use breaks down when you have someone like me, a Black Jew.

In fact, many anti-Semitic ideas of features are rooted in anti-Blackness and vice versa: curly hair, big nose, etc.

Historically, the very idea of racism came initially from Spain and its treatment of Jews during the Inquisition. https://atlasobscura.com/articles/how-racism-was-first-officially-codified-in-15thcentury-spain… these types of racial codifications were later used to entrench chattel slavery in what would become the U.S.

I know lots of white Jewish people are racist. I know lots of Black people are anti-Semitic. I know these communities have hurt each other, and I know from personal experience it is much harder to be Black in the U.S. than it is to be Jewish. But all oppression is connected.

Anyway, there's a lot more to be said but I'll leave it there for now. Go head and ask questions if you're here to learn. Other Black Jews especially feel free to chime in.

Adding this because people keep saying Viacom fired Nick because he's a Black man exercising his freedom of speech. Stop it. Colin Kaepernick was fired for exercising his freedom of speech. Nick Cannon was fired for shooting off racist conspiracy theories.

Viacom is a racist company that has stock in for-profit prisons. Maybe Nick was given a quicker hook than a white person saying the same things would have been. Doesn't make it any less racist or mean Nick should be expected to not face consequences.

Black people: you cannot want people to suffer consequences for racist actions *but only when they're racist against Black people." You also can't have it so Black people aren't also held responsible for racist actions. That's not how justice and liberation works."

After initially taking a defensive position, Nick Cannon has shared posts in the past 24 hours indicating he is open and learning from Rabbis and others who have reached out from the Jewish community to educate him. On Thursday, he shared the following message on Instagram:

"First and foremost I extend my deepest and most sincere apologies to my Jewish sisters and brothers for the hurtful and divisive words that came out of my mouth during my interview with Richard Griffin. They reinforced the worst stereotypes of a proud and magnificent people and I feel ashamed of the uninformed and naïve place that these words came from. The video of this interview has since been removed.

While the Jewish experience encompasses more than 5,000 years and there is so much I have yet to learn, I have had at least a minor history lesson over the past few days and to say that it is eye-opening would be a vast understatement.

I want to express my gratitude to the Rabbis, community leaders and institutions who reached out to me to help enlighten me, instead of chastising me. I want to assure my Jewish friends, new and old, that this is only the beginning of my education—I am committed to deeper connections, more profound learning and strengthening the bond between our two cultures today and every day going forward."

Here's to all of us learning more about the history of all marginalized groups and doing what we can to build bridges between people of all backgrounds.