8 powerful tweets that made the New Yorker cancel a talk with Trump's most infamous supporter.

Remember Steve Bannon? Most people would rather forget. But in today’s media landscape, that’s nearly impossible.

Former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon is an infamous figure.

Considered by some to be the “brain” of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, he was quickly fired from Team Trump after the 2016 election.

He’s the guy most prominently blamed for igniting white nationalist propaganda, promoting Trump’s trade wars with countries like China and encouraging Trump’s most combative tendences.

Or, you might just know him based on his “Saturday Night Live” appearances as the Grim Reaper himself.

Bannon was scheduled to appear at upcoming New Yorker Festival where he would be interviewed by the magazine’s editor David Remnick.

However, after a number of scheduled attendees threatened to cancel their own appearances, Remnick decided to pull Bannon from the schedule in a letter to his staff.

The whole situation has raised even more questions -- not about censorship -- but about whether people like Bannon deserve a forum in the public conversation at all.

On Monday, actor Jim Carrey tweeted his objection to Bannon and reportedly threatened to cancel his appearance at the festival if Bannon was in attendance.

That was followed by an avalanche of other celebrities canceling their appearances.

Some made it clear that they were happy to engage with people who have different political philosophies but that Bannon crossed a line.

Comedian Paul F. Tompkins tweeted about the whole affair in way that perfectly captured why any “outrage” over the cancelation is a waste of energy:

A few people like best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell defended the idea of having Bannon appear but their arguments were quickly shut down by other who said this wasn’t about equal time for different ideas but literally about not giving racists a platform.

Who thought this was going to go well?

For most people, the story will be about Bannon being pulled from the schedule.

But a number of responses have looked at why Bannon was invited in the first place.

Several publications have pointed out that the entire controversy is ultimately good for Bannon as it gives him the very attention he wanted and suddenly makes a largely discredited and ignored political figure suddenly relevant again.

Here’s Remnick’s full letter to The New Yorker staff:

In 2016, Steve Bannon played a critical role in electing the current President of the United States. On Election Night I wrote a piece for our website that this event represented "a tragedy for the American republic, a tragedy for the Constitution, and a triumph for the forces, at home and abroad, of nativism, authoritarianism, misogyny, and racism." Unfortunately, this was, if anything, an understatement of what was to come.

Today, The New Yorker announced that, as part of our annual Festival, I would conduct an interview with Bannon. The reaction on social media was critical and a lot of the dismay and anger was directed at me and my decision to engage him. Some members of the staff, too, reached out to say that they objected to the invitation, particularly the forum of the festival.

The effort to interview Bannon at length began many months ago. I originally reached out to him to do a lengthy interview with "The New Yorker Radio Hour." He knew that our politics could not be more at odds----he reads The New Yorker----but he said he would do it when he had a chance. It was only later that the idea arose of doing that interview in front of an audience.

The main argument for not engaging someone like Bannon is that we are giving him a platform and that he will use it, unfiltered, to propel further the "ideas" of white nationalism, racism, anti-Semitism, and illiberalism. But to interview Bannon is not to endorse him. By conducting an interview with one of Trumpism's leading creators and organizers, we are hardly pulling him out of obscurity. Ahead of the mid-term elections and with 2020 in sight, we'd be taking the opportunity to question someone who helped assemble Trumpism. Early this year, Michael Lewis interviewed Bannon, who made it plain how he viewed his work in the campaign. "We got elected on Drain the Swamp, Lock Her Up, Build a Wall," Bannon said. "This was pure anger. Anger and fear is what gets people to the polls." To hear this was valuable, as it revealed something about the nature of the speaker and the campaign he helped to lead.

The point of an interview, a rigorous interview, particularly in a case like this, is to put pressure on the views of the person being questioned.

There's no illusion here. It's obvious that no matter how tough the questioning, Bannon is not going to burst into tears and change his view of the world. He believes he is right and that his ideological opponents are mere "snowflakes." The question is whether an interview has value in terms of fact, argument, or even exposure, whether it has value to a reader or an audience. Which is why Dick Cavett, in his time, chose to interview Lester Maddox and George Wallace. Or it's why Oriana Fallaci, in "Interview with History," a series of question-and-answer meetings with Henry Kissinger and Ayatollah Khomeini and others, contributed something to our understanding of those figures. Fallaci hardly changed the minds of her subjects, but she did add something to our understanding of who they were. This isn't a First Amendment question; it's a question of putting pressure on a set of arguments and prejudices that have influenced our politics and a President still in office.

Some on social media have said that there is no point in talking to Bannon because he is no longer in the White House. But Bannon has already exerted enormous impact on Trump; his rhetoric, ideas, and tactics are evident in much of what this President does and says and intends. We heard Bannon in the inaugural address, which announced this Presidency's divisiveness, in the Muslim ban, and in Trump's reaction to Charlottesville.What's more, Bannon has not retired. His attempt to get Roy Moore elected in Alabama failed but he has gone on to help further the trend of illiberal, nationalist movements around the country and abroad.

Indoor cats can enjoy the outdoors safely with a harness and leash.

Indoor cats can enjoy the outdoors safely with a harness and leash.

Do any of us still make sourdough?

Do any of us still make sourdough?  A fused glass bowl.

A fused glass bowl.  An example of aquascaping.

An example of aquascaping.  Whittled Halloween figures.

Whittled Halloween figures.  A water color painted bookmark.

A water color painted bookmark.  A cross-stitched pattern of a goddess-like woman.

A cross-stitched pattern of a goddess-like woman.  Latte art.

Latte art. A handmade wood cabinet.

A handmade wood cabinet. A watercolor butterfly.

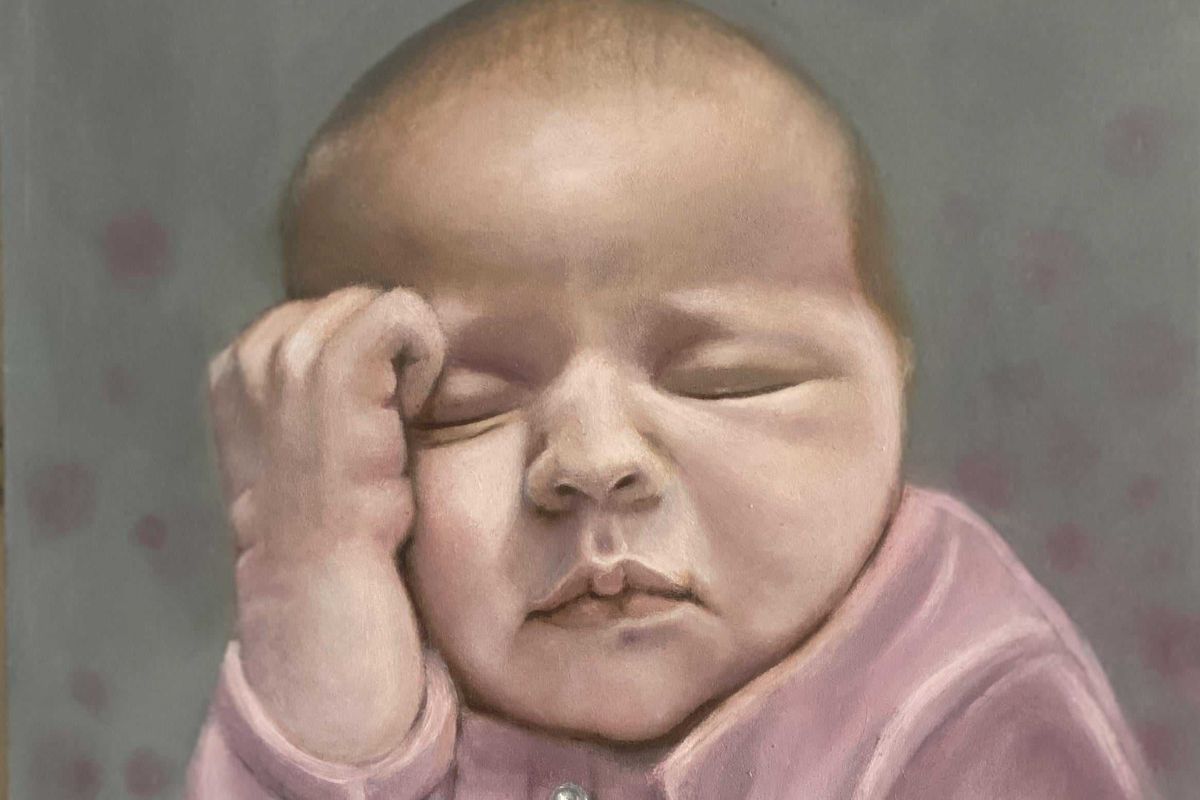

A watercolor butterfly. An oil portrait of a baby.

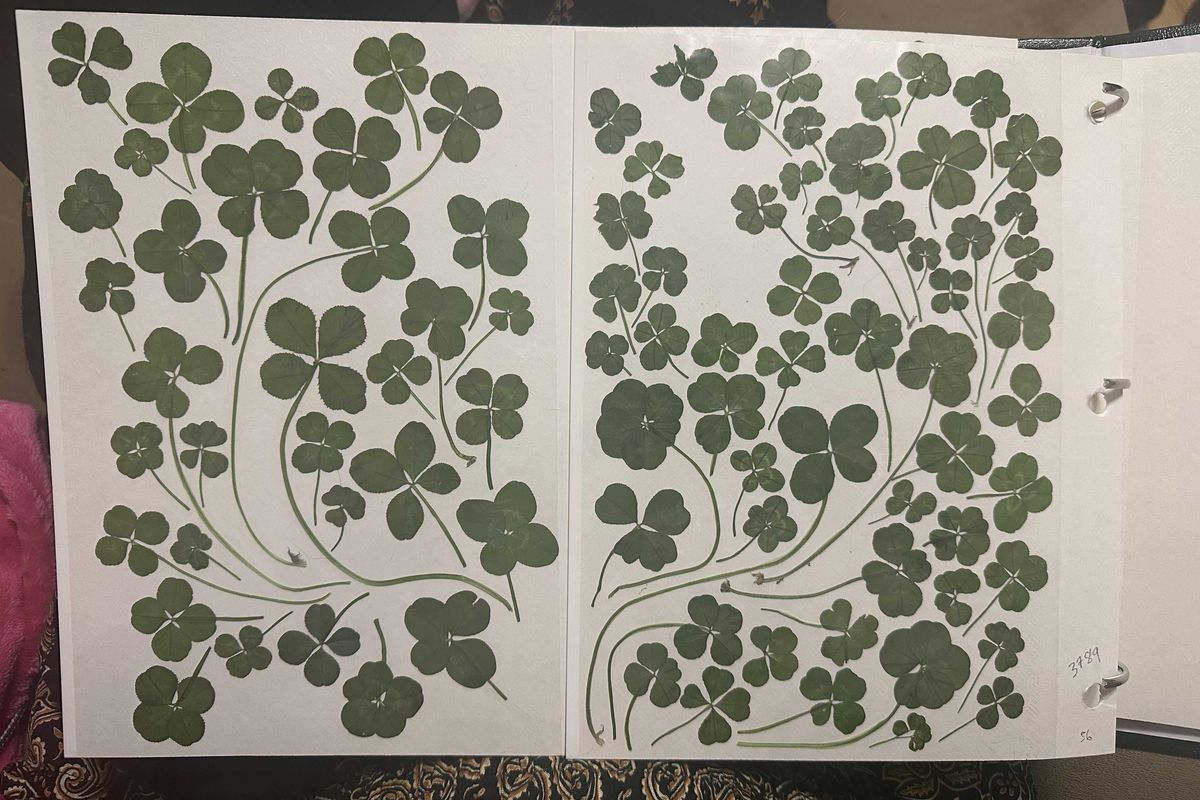

An oil portrait of a baby.  Pressed four leaf clovers.

Pressed four leaf clovers.  A clay pumpkin.

A clay pumpkin.

A Baby Boomer couple.via

A Baby Boomer couple.via  A Baby Boomer couple.via

A Baby Boomer couple.via

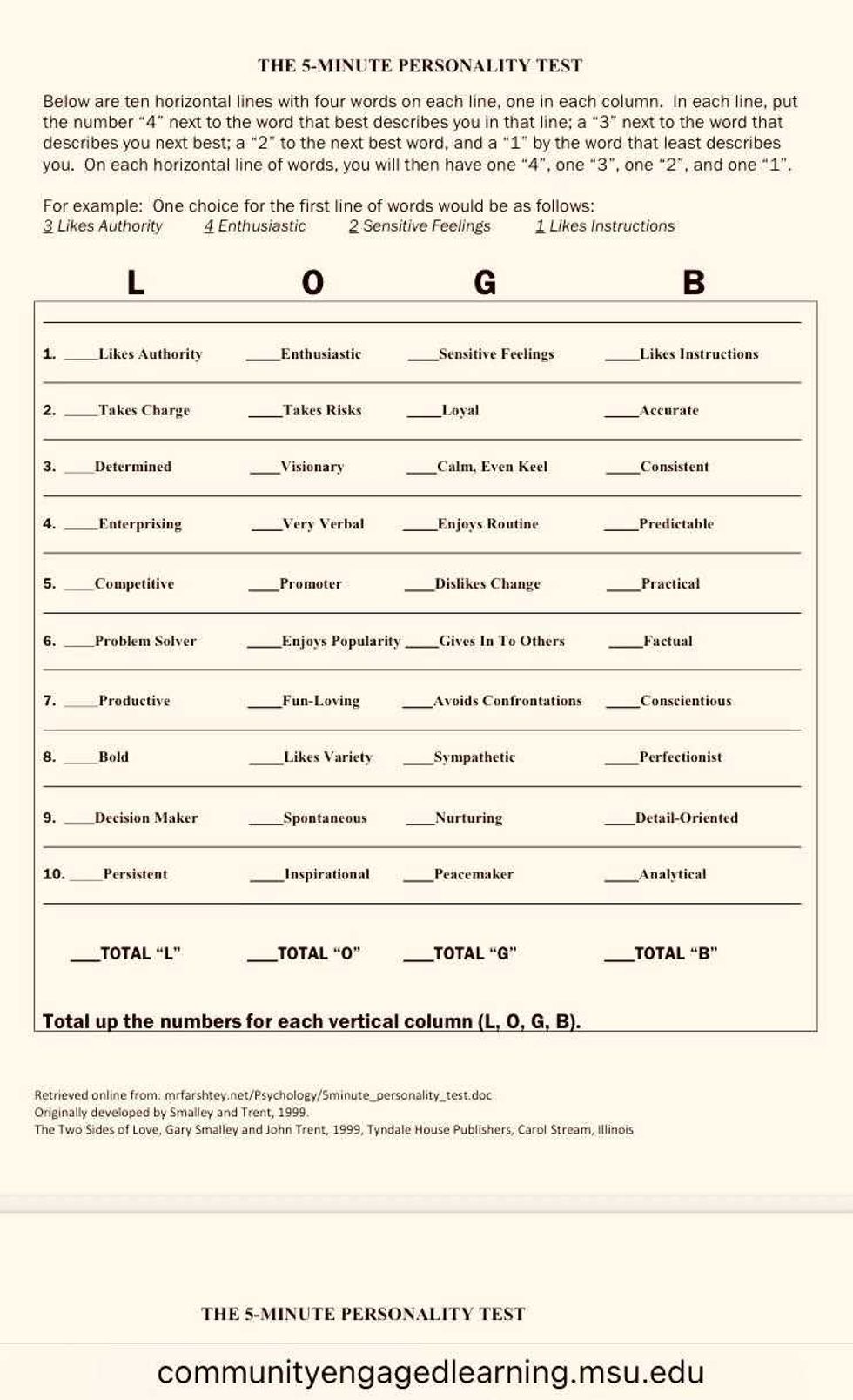

Gary Smalley and John Trent's personality test

Gary Smalley and John Trent's personality test A lion roams.

A lion roams.  An otter is surprised.

An otter is surprised.  Beaver enjoying a snack.

Beaver enjoying a snack.  Golden Retriever adorably looks up.

Golden Retriever adorably looks up.

At least it wasn't Bubbles.

At least it wasn't Bubbles.  You just know there's a person named Whiskey out there getting a kick out of this.

You just know there's a person named Whiskey out there getting a kick out of this.