9 amazing, everyday things that you never knew were invented by kids

You can thank an 11-year-old for popsicles.

Kids and teens have invented a lot of things we use every single day.

A girl named Margaret Knight was 12 years old in the 1850s when one of her friends was injured working in a cotton mill. She couldn't solve child labor, which wouldn't disappear for another several decades, but she did have an idea to keep kids like her friend safer. Knight was shortly thereafter credited with inventing a "safety loom" for use in the mills. It wasn't just some ambitious side project. The Library of Congress reports that a variation of her design was "in universal use" by 1913. Years later, Knight went on to invent none other than the paper bag. It may not seem like an earth-shattering invention now, but at the time, a bag that could stand upright on its own was incredibly useful.

Suffice it to say, kids have been coming up with awesome ideas and turning them into real inventions for centuries. Their active imaginations and natural optimism make them ideal inventors. Here are some relatively-everyday things most people have no idea were invented by kids and teenagers.

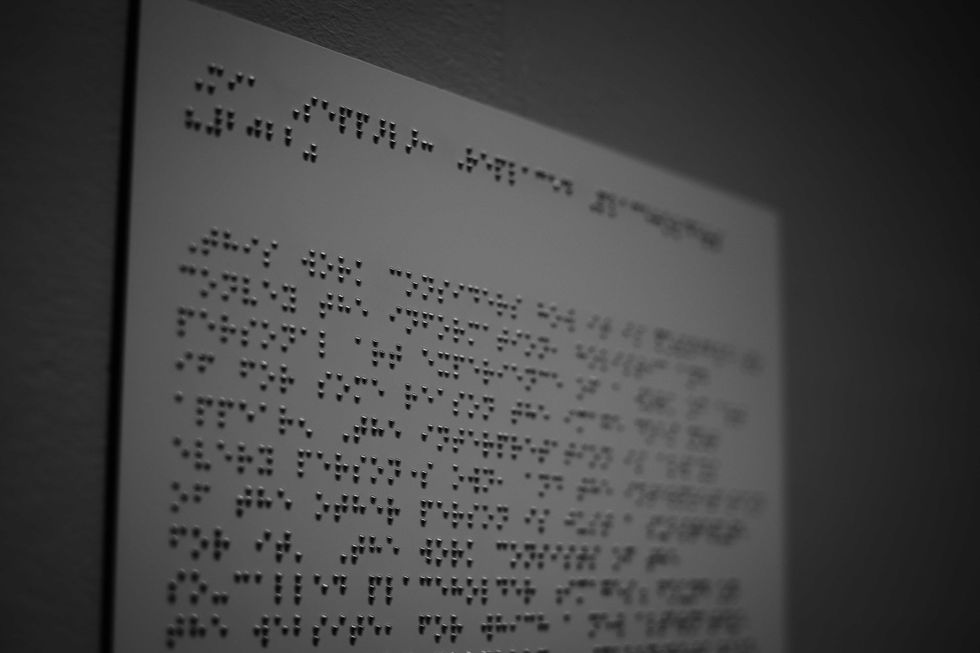

1. Braille

Louis Braille lost his sight at just three years old due to an eye infection stemming from an accident. In school, he learned about a cryptography system used by the French military for nighttime battle communication and had the idea to adapt the concept into a form of reading and writing for the visually impaired.

In 1824, when he was 15, Braille presented his finalized system of raised dots on paper to peers for the first time. Today, braille is in almost universal use.

2. Trampolines

George Nissen of Iowa was just 16 years old when he got an idea by watching aerialists at the circus. The artists would fly through the air before landing into a safety net, but he wondered if there was a way in which they could bounce back up and continue tumbling. The idea for the trampoline was born, and though it took him a few years and failed attempts, he did eventually secure a patent for his "tumbling device."

- YouTube www.youtube.com

3. Christmas lights

Though the electric light bulb was created by Thomas Edison in 1879, and he even had the idea to string them together for decoration, Christmas lights initially had a hard time catching on. People were skeptical of electricity at the time and preferred to light their trees with candles.

Needless to say, this was a beautiful but outrageously dangerous method:

- YouTube www.youtube.com

It wasn't until 1903 that Albert Sadacca, a teenager whose parents owned a lighting company, created colorful strings of lights that were safer and far more affordable than anything else available at the time. The Library of Congress adds that, prior to Sadacca's design, lighting a Christmas tree with electric lights would have cost the equivalent of $2,000.

4. Popsicles

Eleven-year-old Frank Epperson was drinking a soda on a cold San Francisco day in 1905. He'd been using a simple wooden stick to mix the powdered soda into water, and left the whole concoction outside overnight after a long day of play. The next day, it was frozen solid, and Epperson realized it was delicious.

It took a few years for Epperson to begin selling his creation around town, and eventually the named was changed from Ep-sicles to Popsicles at the behest of his children: Pop's 'Sicle.

5. Earmuffs

Fifteen-year-old Chester Greenwood was tired of suffering through brutal Maine winters in the late 1800s. He tried wrapping a thick scarf around his head to keep his ears warm but found it cumbersome and ineffective. But the failure did give him another idea. He bent a piece of wire into a shape that would fit around his ears and asked his grandmother to sew beaver fun onto the loops.

He tweaked the design several times before arriving on his final version, which he received a patent for in 1877 at the age of just 18.

6. Swim flippers

Benjamin Franklin (yes, that Ben Franklin!) was just 11 when he came up with the idea for swim flippers. Of course, his original design went on your hands instead of your feet, and they were essentially wooden paddles rather than flexible flaps of rubber. But they were an excellent proof of concept from the avid swimmer.

In 1773, he wrote, "In swimming I pushed the edges of these forward, and I struck the water with their flat surfaces as I drew them back. I remember I swam faster by means of these pallets, but they fatigued my wrists."

7. Wristies

Anyone who's ever spent time out in the cold knows how annoying that little gap between your glove and coat can be. Cold air pours in, stinging your skin and leaving you uncomfortable.

Ten-year-old KK Gregory was equally annoyed by this, but had a brilliant idea to combat the cold: She worked with her mother to create fuzzy wrist-sleeves that would bridge the gap from coat to glove and help keep her arms warm. Today, Wristies is a thriving business and has been one of the pioneers of the popularity of glove-liners and the like.

8. Calculators

Though various adding machines (like the abacus) have existed for centuries, you might be surprised to know that one of the earliest mechanical calculators was invented by a French teenager in 1642.

NPR writes, " The family business involved a lot of tedious arithmetic, so Blaise Pascal came up with a machine - a wooden box with a series of dials connected to cogs and levers to help his dad with some of that adding and subtracting. He invented, basically, a calculator, and he was 19 years old."

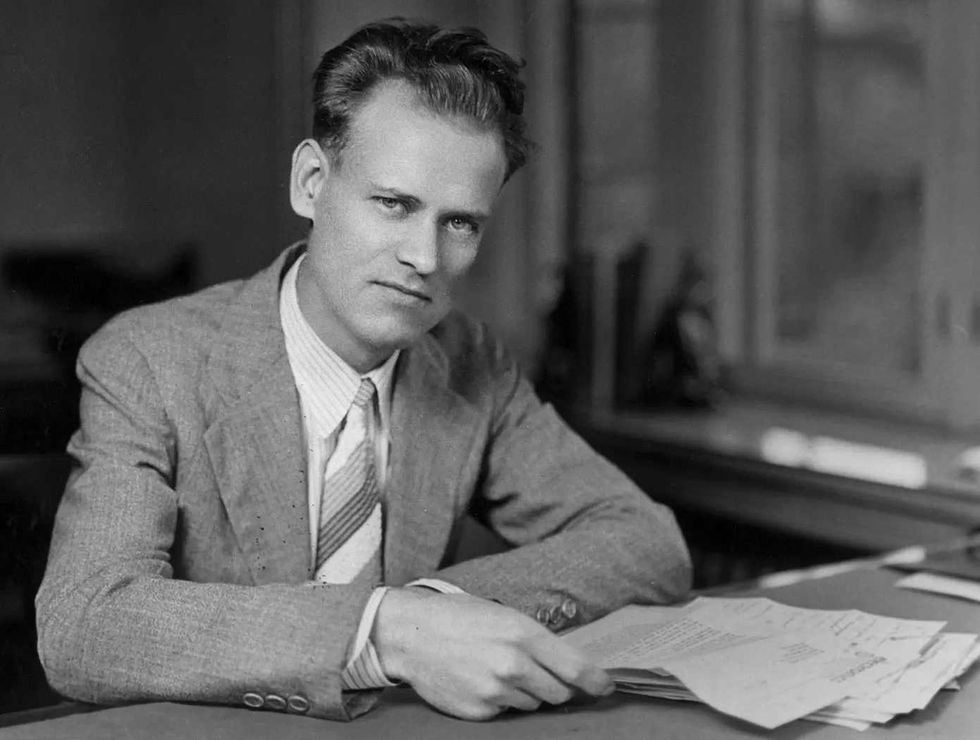

9. The television

A humble, TV-loving farm boy named Philo Farnsworth was inspired by the neat rows of lines he'd create when plowing the fields. Mechanical televisions existed at the time, but Farnsworth figured there might be a way to scan images in a line pattern instead. He was a teenager when he began his work and research on the necessary components, and was 21 when he "developed what he called the 'image dissector,' the first working electronic camera tube, in San Francisco in 1927. His work led him to invent the first fully electronic television system," writes Elon University.

There are many incredible inventions by young people that continue to make waves behind the scenes and in the realms of health and science.

Seventeen-year-old Ryan Patterson invented a glove that detects American Sign Language and displays the words as easy-to-read text. His ideas have been iterated and improved upon by other researchers, and now sign language gloves are widely available for certain uses. Patterson won the Junior Nobel Prize for his work.

When he was 14, Javier Fernandez-Han created a system that turns sewage and algae into renewable energy.

Much like the story of the popsicle, kids are also great at discovering amazing things by accident. A middle-schooler in Chicago recently discovered a new compound in goose poop that shows potential for treating human cancer cells.

The 3M Young Scientist Challenge showcases the best and most innovative inventions by young people all over the world each and every year. Recently, finalists and winners in 2025 including Kevin Tang, a 13-year-old who created a real-time fall detection system for seniors. Aashritha Pasam created a wildfire detection alert system. Fourteen-year-old Amaira Srivastava from Arizona invented biodegradable cups infused with fruit peels to fight plastic waste and food loss.

Young people are absolutely amazing, and if you stop to look around and take the time to learn about the origins of some of the everyday items we take for granted, you'll gain an even greater appreciation for their natural curiosity.

- Woman designs a chair specifically for half-dirty clothes to hang on, and people feel so seen ›

- Mom creates 'invention box' that gives her kid hours of independent playtime ›

- Glass cars, sentient spoons, and an inventor who's challenging our idea of normal. ›

- Celebrate Women's History Month with 12 awesome things invented by women. ›