How one man roller-skated 685 miles to attend Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'I Have A Dream' speech

Tweeted by the Smithsonian NMAAHC.

When Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, he was met by nearly 250,000 people. Traveling from all over the country to participate in the March on Washington, this crowd became part of one of the most iconic and pivotal moments in civil rights history.

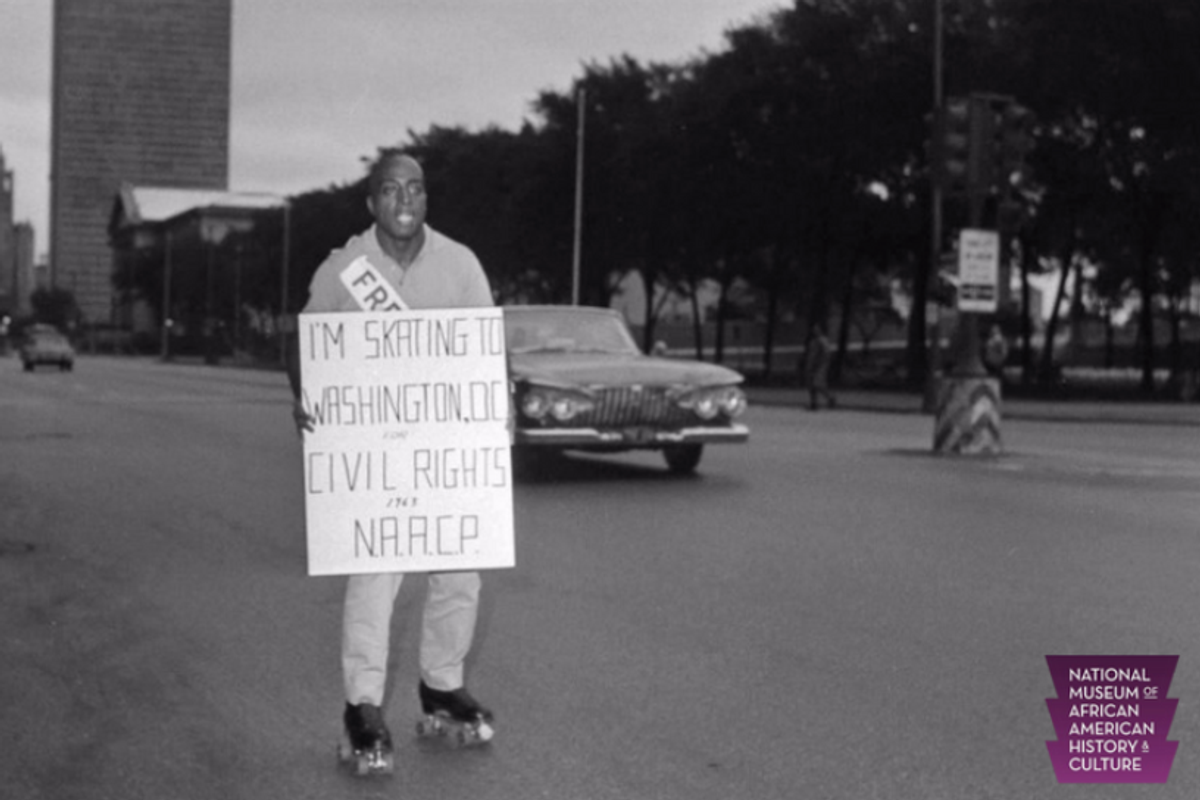

Joining those thousands at the Lincoln Memorial was Ledger Smith, a 27-year-old athlete and entertainer who traveled all the way from Chicago … on roller skates.

Ledger’s story might be lesser known, but it’s an inspiring one.

As a semiprofessional skater, Smith, better known as “Roller Man,” was known for his impressive tricks.

Deciding to really put his skills to the test, Ledger skated 685 miles, from Chicago to Washington, D.C. … for 10 straight days. My legs are sore just thinking about it.

When a 1963 publication of the Baltimore Afro-American asked him why, Smith replied that it was “to dramatize the march,” adding that he “did it in the slowest way.”

To prepare for his journey, Smith ran 5 miles every day for two weeks prior. And after skating for 10 hours a day for a little over a week, he arrived having lost 10 pounds.

Wearing a freedom sign across his chest, Ledger helped spread inspiration along his route. He wasn’t always met with encouragement. At one point a man had tried to run him down with a car in Fort Wayne, Indiana, according to a radio interview with WAMU.

Still, Ledger was also met by well wishers. The Afro-American reported that many people along the highway, some of them white, wished Ledger good luck, saying that they’d see him in Washington.

Determination (and incredible stamina) overcame the obstacles. Because on Tuesday, Ledger arrived, “sore, aching, but hoping he was 700 miles closer to freedom,” according to the report.

Ledger met up with his wife—who decided to go the more traditional route and travel by train—along with celebrities, activists and protestors to take part in the massive March on Washington. The couple witnessed firsthand the words that would become a beacon of hope for the future, and an emblem of black resilience.

Following nine other speakers, King had only planned on being at the podium for four minutes. But when prompted by gospel star Mahalia Jackson to “tell ‘em about the dream,” he stood on stage and spoke for 16 minutes. Though the speech notably ties in themes from the Declaration of Independence, the Gettysburg Address, Shakespeare and the Bible, its most famous section was completely improvised.

Full of poetry and vigor, King challenged his community to “not wallow in the valley of despair,” and painted the picture of “walking together as sisters and brothers,” where King called it his dream, but it was Ledger’s dream too, along with countless others who arrived that day.

Ledger Smith was a 27-year-old, Chicagoan truck driver, who roller-skated 100 miles to attend the #MarchOnWashington. #APeoplesJourney pic.twitter.com/YSi9YaiufY

— Smithsonian NMAAHC (@NMAAHC) August 28, 2017

Ledger’s journey to Washington powerfully symbolizes the great lengths that African Americans had endured, were enduring—and still are enduring—to attain equality. But for Ledger, and the thousands that joined him, no distance was too great, if the long road leads to “free at last.”

- Celebrate Black History Month at Upworthy market by supporting ... ›

- Maryland high schoolers' Black History Month step routine will blow ... ›

- There are plenty of things to celebrate about Black Wall Street that ... ›

- Roller-skating brothers spread joy and culture - Upworthy ›