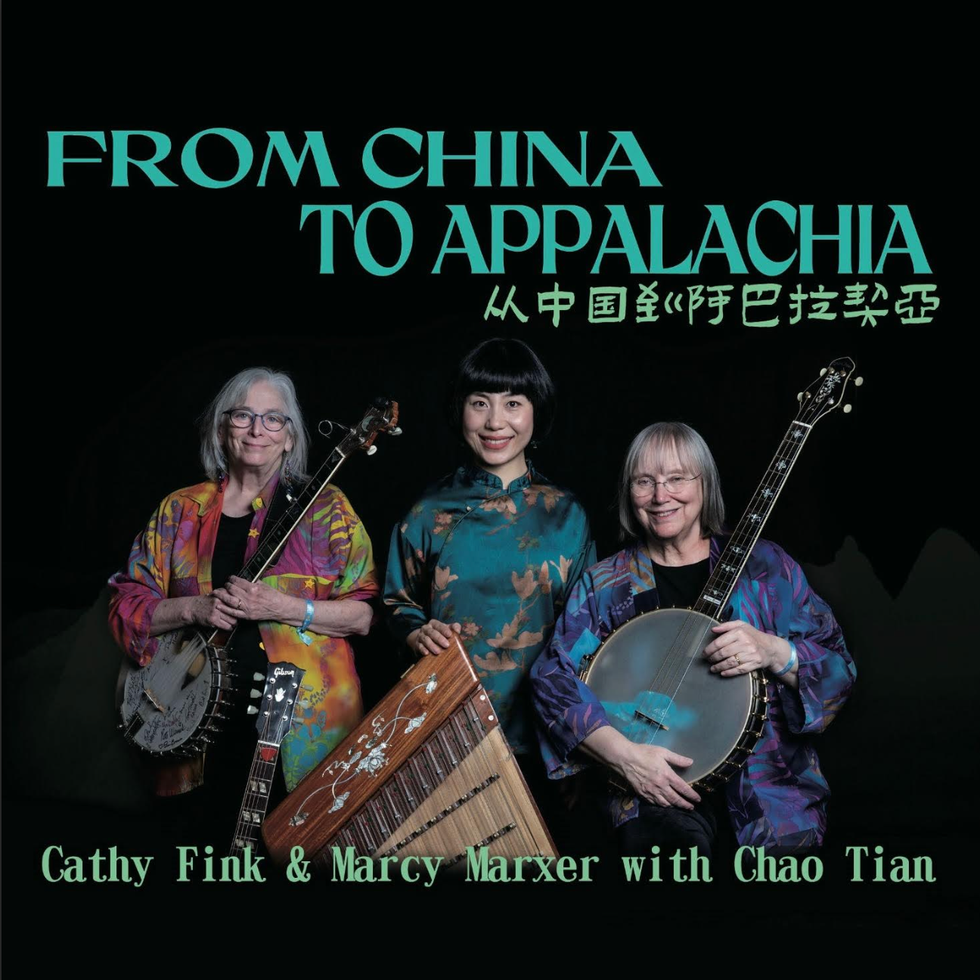

Appalachian banjoists and Chinese dulcimer player create the coolest musical mashup ever

As one person said, "This is literally what America is all about."

"From China to Appalachia" blends musical instruments and styles in perfect harmony.

One of the best things to come out of social media is the proliferation of musical mashup videos. We've seen Irish step dancers tapping to Beyonce's country music, Scottish bagpipes played with Indian drums, the Star Wars "Imperial March" with a hip-hop twist, and other blends of music and culture coming together in beautiful harmony.

Just when we think we've seen and heard it all, we get something entirely new: two banjo players from Appalachia and a yangqin (Chinese hammered dulcimer) player jamming out together. The three women—Cathy, Marcy, and Chao Bob—sit with their instruments on a screened-in porch, and once they introduce themselves and start to play, something magical happens.

@cathybanjo Appalachian Tunes with Chinese Accent- FROM CHINA TO APPALACHIA #chinatoappalachia #fromchinatoappalachia #banjo #yangqin #CELLO-BANJO #cathyfink #MarcyMarxer #chaotian #improvisation #worldmusic #GLOBALMUSIC #CULTURALDIPLOMACY #FYP @broskireport #TAKEACHANCE #MAKEMUSIC @chaotianmusic #collaboration @_world.music #grammy

The sound of the banjos and the yangqin are surprisingly similar and blend well together, and as the musicians play, the style alternates between traditional American folk and traditional Chinese music. Back and forth in perfect balance, the musicians showcase one another and then unite as one, creating a moving effect that's difficult to put into words.

People in the comments summed it up, though:

"This is literally what America is all about to me."

"Cultural exchange is so beautiful idk why anyone would discourage it."

"This is what America should be, a true melting pot! Fantastic music, ladies!"

- YouTube youtu.be

"I love how you can hear the Appalachian music and the Chinese influences, it doesn't overshadow or overwhelm each other and it goes really well together."

"It feels like a conversation or a dance."

"It sounds like a river flowing into a waterfall."

"Music is the universal language."

With nearly 3.5 million views on Cathy Fink's TikTok page, the mashup clearly—and literally—struck a chord with people. But how did this "From China to Appalachia" collaboration happen in the first place?

Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer were already a Grammy award-winning duo focused on American Roots music. For the past 20 years, Fink has served as a mentor and advisor to Artists in Residence at the Music Center at Strathmore in North Bethesda, Maryland.

"It is the only PAC of its kind, nurturing the art and career of six young musicians (16 to 32) per year with business, professional and artistic workshops," Fink shares with Upworthy. Chao Bob, a classically trained virtuoso on the yangqin, was one of the Artists in Residence in 2017, and Fink invited her to a jam session with her, Marcy, and a few other musicians.

"Chao came to the jam session with her limited English, thinking it was about food!" Fink shares. "She didn’t understand why we told her to bring her instrument. In a short period of time, she realized there was no written music and everyone was truly improvising with each other. She said she fell in love with that and never looked back. She also fell in love with the sound of southern American old-time music with fiddle tunes, songs, modal sounds and harmonies."

The women know their musical collaborate has the potential to bring people together. "We, all three of us, believe in people-to-people diplomacy," Fink says, "in cultural diplomacy, in the fact that we're all humans and individuals who want the same love and peace and happiness together."

Fink shares that the trio played a few shows together, including a big show in Ashe County, North Carolina, to see if the idea of interweaving their music would work for a Southern audience. "It was amazing," she says. "With that stamp of approval, we continued building repertoire, skills to play music from each other’s cultures, and performing more widely."

The trio has toured and made a CD which led to an NPR piece on Morning Edition, BillBoard top bluegrass charts, and folk charts. Their album, From China to Appalachia, is available on streaming services and from their website here. The group will be touring again this summer.

"This summer/fall we’ll be performing at the Old Songs Festival (New York), NPR’s Mountain Stage (West Virginia), Winnipeg Folk Festival, Torrance Cultural Arts (California), Lotus World Music Festival and a home-town show at the The Music Center at Strathmore on November 9 (Maryland)," Finks shares. "We’re working on a new album and there are more new adventures coming!"

Definitely looking forward to that. You can find the tour schedule and join their mailing list at cathymarcy.com.

- Musical mashup at Scottish-Indian wedding is a delightful blend of cultural traditions ›

- Mother and son gave Radiohead's 'Creep' an Indian twist that's moving people to tears ›

- Man transforms 'Phantom' and 'Les Mis' hits into acoustic folk songs, much to everyone's joy ›

- Chinese teacher translates bad Chinese tattoos, and people are cracking up - Upworthy ›

- Adam Met shares his 'hurricane model' for building fan bases and meaningful climate movements - Upworthy ›