Lucia Maya remembers getting a phone call from her 21-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. She was in agony.

A creative writing student at the University of Arizona, Elizabeth had been dealing with intense pain in her chest for weeks, along with swelling in her neck and face. The student health clinic told her it was probably bad allergies.

“She called me one day in tears because she was in a lot of pain,” Lucia said. “She wasn’t one to cry or complain. I said, ‘OK, something is clearly wrong.’”

Elizabeth was rushed to the emergency room, where an X-ray revealed a tumor in her chest the size of a baseball. The diagnosis was non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

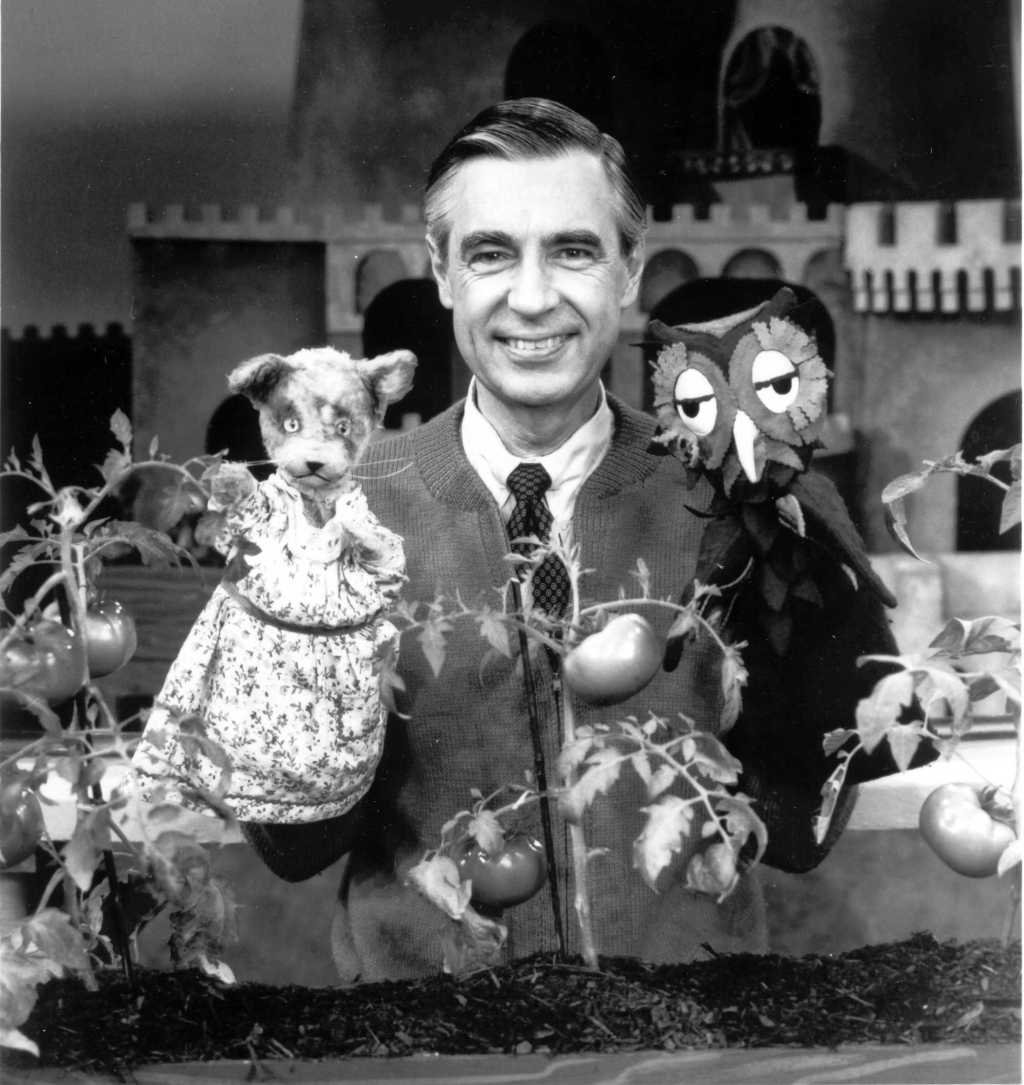

Lucia (right) and her daughter, Elizabeth. Photo by Jade Beall, used with permission.

Six rounds of chemotherapy initially beat the cancer back, but soon it had spread to Elizabeth’s brain. Not even a year after first discovering the pain, Elizabeth was placed in hospice care. She’d spend her final days in her mother’s home.

There was nothing more the doctors could do.

Lucia was suddenly in the strange and tragic position of having to plan a funeral for her daughter while she was still alive.

The first step for many people who are grieving is to make arrangements with a funeral home. But there’s another option gaining popularity with many families: home funerals.

Joanne Cacciatore, a research professor at Arizona State University who studies traumatic death, wants people to remember that caring for our own dead used to be, well, just the way things were done. It was around the Victorian Era (the mid- to late 1800s) that both birth and death were institutionalized, or shopped out to experts who had special tools and training.

She said more and more people are now bucking that norm and skipping the mortician altogether.

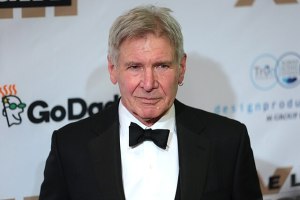

Photo by Jade Beall, used with permission.

A home funeral often involves bypassing the usual embalming process, instead opting for more gentle methods of preserving the body: keeping it cool with dry ice and bathing it, for example. Some families will hold a viewing at home before sending the body off to be prepared for a traditional burial or cremated. Others, depending on local laws, bury their loved ones on family land instead of in a cemetery.

While home funerals are often much less expensive then traditional ceremonies, Cacciatore said this choice isn’t usually about money. For many people, it’s about healing.

“I think it has a therapeutic effect, in that when the person you love has died, and they’re at home, you can check in with that reality as often as you need,” she said. “You can go in that room, you can sit in that room 24 hours a day for three or four days, and you can watch their body, and see that they’re not there.”

For other people, they wouldn’t dream of doing things any other way.

“Who better to take care of someone you love so much than you?” Cacciatore said.

After two months of being cared for by her mother, Elizabeth passed away on a Sunday in late 2012.

Elizabeth’s body was kept at home for two days and covered in silks and fabrics. Photo by Lucia Maya, used with permission.

Elizabeth hadn’t eaten for weeks. Her mother woke up at 4 a.m. the day she passed away, sensing the moment was about to arrive. Lucia held her daughter’s hand as she took her last breath.

By this point, Lucia, her partner, Elizabeth’s father, and even Elizabeth herself had decided a home funeral was right for them, though Elizabeth didn’t like talking about it much. She was at peace with whatever was going to happen.

“What was so lovely was that we knew there was no rush to call the funeral home to come pick up her body,” Lucia said. “We knew that we had time.”

Lucia and her sister bathed Elizabeth. Anointed her body with oils. Laid her on a table with dry ice packed underneath. Wrapped her in beautiful silks and cloths, with rose petals sprinkled on top.

Photo by Lucia Maya, used with permission.

On Monday, family and friends came and went, saying their goodbyes in the place Elizabeth called home. A friend brought a cardboard box that would later be used to transport Elizabeth’s body, and visitors decorated it and filled it with notes of love.

On Tuesday, Lucia and close family members placed Elizabeth in the box and drove her to the crematory. They watched as her body entered the cremation chamber. Lucia thought it might be too difficult to watch, but she said when the moment came, she was ready.

By then, she felt her daughter’s body was nothing but an empty vessel.

“It felt so healing to be able to do those last things to take care of her,” Lucia said.

“To be the one to bathe her, gently, to be the last one to dress her, to cover her with these beautiful silks that I know she would have loved — it would have felt very, very strange to send her body off and have some strangers doing those things for her, no matter how loving and caring they might have been.”

She knows a home funeral isn’t the right choice for everybody, but she shared her story because she wants people to at least know that it is a choice.

For Lucia, being able to make that choice means she gets to live without a single regret about how she spent her final days with her daughter.