America's race to the top in education is likely responsible for the financial illiteracy crisis

We were once chastised for schools focusing "too much" on preparing kids for adulthood.

America's competition with Russia likely created the U.S. financial literacy crisis

There are often jokes about kids not knowing how to write a check or how to do other basic adulting tasks, though no one really writes checks anymore. But it's not just teens or young adults that lack some of these basic life skills, there are people in their 30s and 40s that don't fully understand how interest works.

Due to economic disparities across the country, all schools don't receive the same standard education. Some schools require students to take classes like life skills, adult skills, career readiness, or financial literacy classes as part of their graduation requirements. In other schools they're there as electives while some schools don't offer those classes at all leaving students underprepared for adulthood.

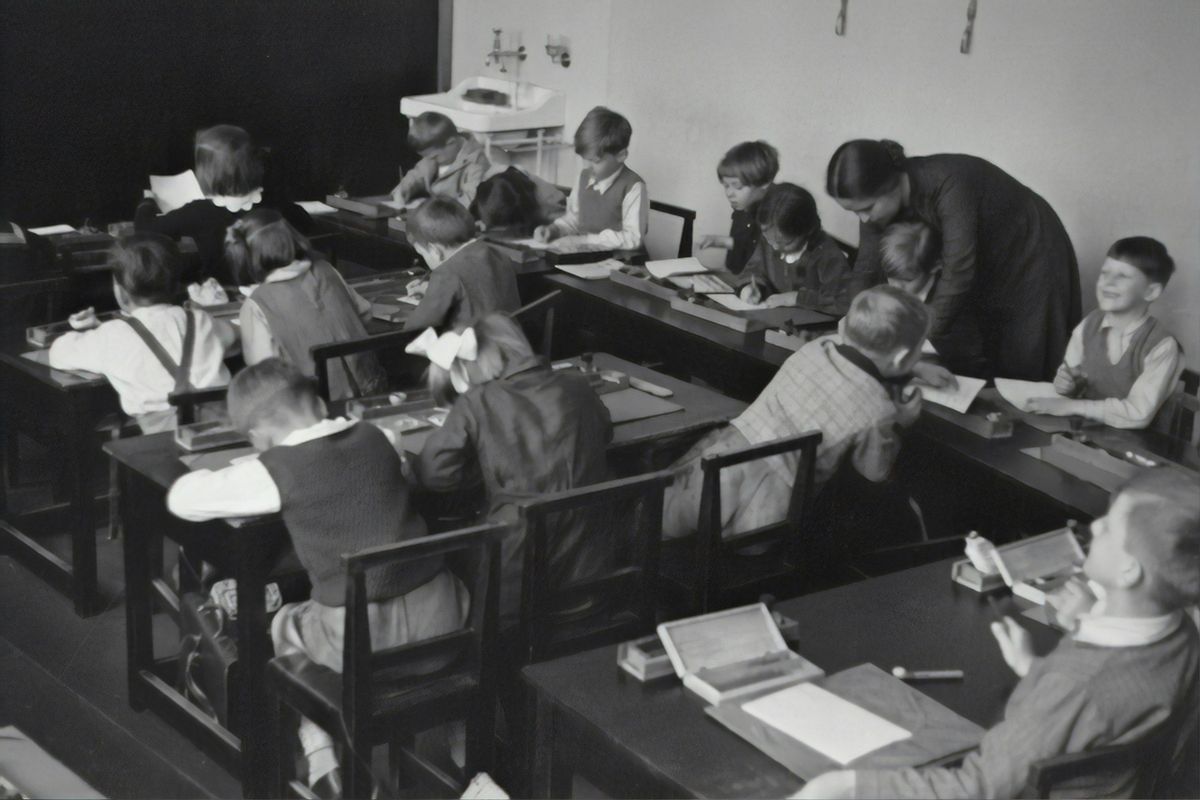

This wasn't always the case though, at one point in the history of American education, these sorts of classes were the norm. This ensured that students graduating in America had basic financial literacy and adult skills. So what happened?

"Based on old teaching materials, it seems that up until the fifties or sixties, money management was a fixture in the public school curriculum, often as part of home economics class. Alongside, you know, sewing and baking, students were learning how to budget for better living, use consumer credit and save for their weddings. There were also stand along consumer education classes, which seemed to be less gendered." Vox says.

Public schools shifted from this useful norm in 1958 when President Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act after feeling America was falling behind Russia. This was during the big race to get into outer space and Russia, then known as the USSR, seemed to be coming out ahead. The bill was designed to focus on core classes like math, science and a foreign language, but after the Department of Education was formed, their first report was scathing.

In 1983, the Department of Education released a report titled "The Imperative for Education Reform," which basically blamed the country's "declining educational performance" on schools focus on adulthood.

"Twenty-five percent of the credits earned by general track high school students are in physical and health education, work experience outside the school, remedial English and mathematics, and personal service and development courses, such as training for adulthood and marriage," the report scolds.

This sharp critique resulted in several subsequent presidents to focus on ways to measure educational progress in the areas Eisenhower and the Department of Education originally outlined. Standardized testing became a heavy source of measurement, oftentimes tied to teachers maintaining their employment. For many students this meant their education revolved around the teacher prioritizing items that would be measured on the standardized test.

The shift to strict measurement of growth via standardized testing caused students to fall behind on other much needed skills. Americans have been noticing the shift in not only adult skills, but financial literacy and it's been a multi-decade slide that seems to be changing trajectory in recent years.

In a 2019 National Bureau of Economic Research study, researchers report that 57% of U.S. adults are financially illiterate. Vox reports that over the past decades more students are spending full semesters in financial literacy classes, learning things like budgeting, taxes, student loans and more. Though more states are offering these courses to high school students, only nine states have a stand-alone financial literacy course as a graduation requirement.

Other states offer the lessons within the framework of another class or as a stand-alone elective course, though in 2024 seven additional states introduced legislation to make the course mandatory. Financial literacy not only helps the individual, but their family and eventually the economy, so hopefully we will see these personal finance courses reintroduced nationwide.