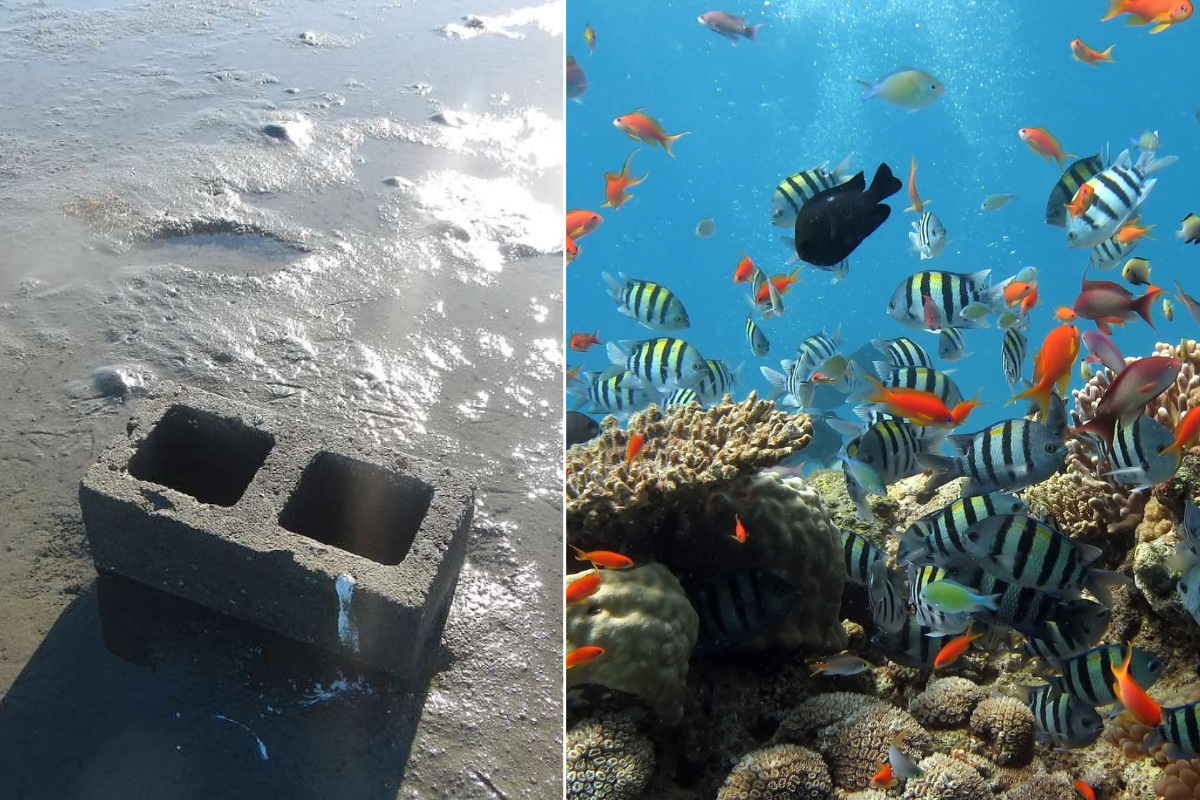

Scientists left cinderblocks in a barren part of the sea. 3 months later they were ecstatic.

Coral reefs are dying at alarming rates. Concrete may be a creative solution.

Scientists are turning simple concrete into the building blocks for a healthier ocean.

A viral video has been making the rounds lately that shows a giant (and extremely bizarre) ship opening up at its middle and dropping a metric buttload—that's the official term—of cinderblocks directly into the ocean. The video is fascinating, so much so that I was certain it was AI-generated at first. After all, what kind of ship can part down the middle like that?

Turns out, the video is real! The ship is called a split hopper barge and is often used to transport and deliver dredged soil. Dumping concrete like this looks like the world's worst case of littering, but in actuality, the concrete blocks serve an important purpose that benefits sea life of all varieties.

But how?

For answers, look no further than the GARP — that's the Grenada Artificial Reef Project (also known as the Grand Anse Artificial Reef Project or GAARP).

With coral reefs under threat and disappearing all over the world, the team behind the project came up with an interesting solution they wanted to test out.

In 2013, the scientists placed four concrete pyramids (basically, cinderblocks stacked together into something of a tower structure) in a barren part of the Caribbean Sea. The location was just off the coastal beaches of Grenada.

In just 3 months, the pyramids had attracted tons of marine life.

The block pyramids gave shelter to the animals who otherwise had nowhere to hide, nest, or feed in this part of the water. "An initial growth of algae and colourful encrusting sponge was soon followed by a varied range of invertebrates. These included feather duster worms, lobster, crab, and urchins. Excitement developed as we started to see a range of juvenile fish including squirrel fish, goat fish, grunts and scorpionfish," says the official website.

After a year, word must have spread among the fish, because the simple concrete blocks transformed into "buzzing diverse communit[ies] of marine life."

At around 18 months, things started to get really exciting. Stony and brain corals, described as the "building blocks of coral" began to appear on the pyramids.

Over the following 10 years, the project has exploded with more and more coral growing on the blocks and more fish and other sea life moving in. "Each subsequent year more pyramids have been added to increase biomass. GARP is becoming a balanced ecosystem, home to over 30 species of fish, 14 different kinds of corals and many of the invertebrates and algae you would find on a naturally occurring reef."

Today, there are upwards of 100 pyramid blocks in the location. Other, similar projects are taking place in waterways all over the globe.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

GARP/GAARP isn't the first or only project of its kind. Concrete has been shown again and again to make an excellent shelter for marine life and a perfect launching pad for new coral growth.

People have tried other materials before, to varied results. One such project off the coast of Florida in the 1970s utilized millions (!) of old tires in an effort to create new fish habitats. Called the Osborne Reef, the effort is now considered a major ecological disaster as storms and sea currents have tossed many of the tires around, washing them ashore and even damaging otherwise healthy natural reefs nearby. Talk about a backfire. Major clean up initiatives to undo the damage are still underway.

Specialized concrete structures are heavy enough to stay put in rough conditions and are one of the few things that can withstand years and years of being battered by rough, salty seawater without degrading.

from nextfuckinglevel

Coral reefs are disappearing around the globe at an alarming rate. Physical damage, both natural and manmade, along with pollution, coral harvesting, global warming, and bleaching wreaks havoc on natural ecosystems under the sea.

Coral reefs aren't just there to look pretty. They dampen waves and currents before they hit land, reducing erosion and protecting people who live on the coast. Reefs are home to a huge variety of marine life who use it for shelter and finding food. And, finally, they're amazing destinations for scientific discovery—new species and even medical treatments are being discovered on reefs all the time!

All that and the very existence of coral reefs may be in jeopardy, according to the EPA.

There's no easy fix to this grave problem. Natural coral reefs take thousands of years to grow and mature. So, even with all the cinderblocks in the world acting as growth platforms, it would be impossible for us to replace all the coral we've already killed or destroyed. Saving our oceans must be a multi-faceted effort, with initiatives that combat pollution and rising sea temperatures in addition to creating artificial reefs.

But projects like GARP/GAARP are an awesome start. They may not save the planet all on their own, but if you ask me, those fish look pretty darn grateful for their new home.

This article originally appeared in June