6 beautiful drawings by LGBTQ inmates that illustrate life in prison

Their artwork shows their strength, resilience, and talent.

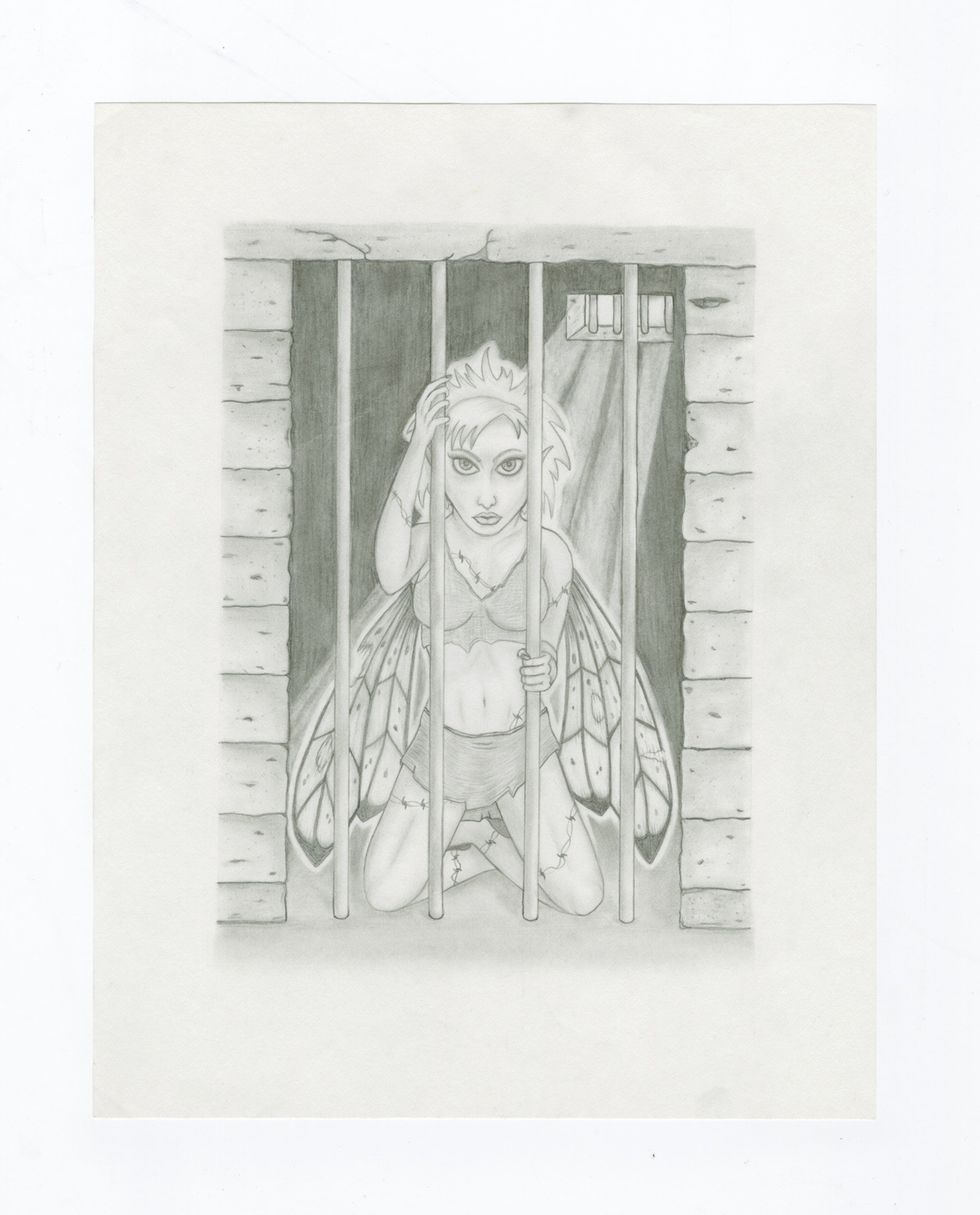

"Acceptance" by Stevie S.

Tatiana von Furstenberg laid out more than 4,000 works of art on the floor of her apartment and was immediately struck by what she saw.

The pieces of artwork were submitted from various prisons across the country in hopes of being featured in "On the Inside," an exhibition of artwork by currently incarcerated LGBTQ inmates, curated by von Furstenberg and Black and Pink, a nonprofit organization that supports the LGBTQ community behind bars. The exhibit was held at the Abrons Arts Center in Manhattan toward the end of 2016.

"I put all the submissions on the floor and I saw that there were all these loving ones, these signs of affection, all of these two-spirit expressions of gender identity, and fairies and mermaids," von Furstenberg said.

"These artists feel really forgotten. They really did not think that anybody cared for them. And so for them to have a show in New York and to hear what the responses have been is huge, it's very uplifting," she said.

Plenty of people turn to art as a means of escape. But for the artists involved in On the Inside, the act of making art also put them at risk.

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people are incarcerated at twice the rate of heterosexuals, and trans people are three times as likely to end up behind bars than cisgender people. During incarceration, they're also much more vulnerable than non-LGBTQ inmates to violence, sexual assault, and unusual punishments such as solitary confinement.

Not every prison makes art supplies readily available, either, which means that some of the artists who submitted to "On the Inside" had to find ways to make their work from contraband materials, such as envelopes and ink tubes. And of course, by drawing provocative images about their identities, they also risked being outed and threatened by other inmates around them.

But sometimes, the act of self-expression is worth that risk. Here are some of the remarkable examples of that from the exhibition.

(Content warning: some of the images include nudity.)

1."A Self Portrait" by B. Tony.

“A Self Portrait” by B. Tony

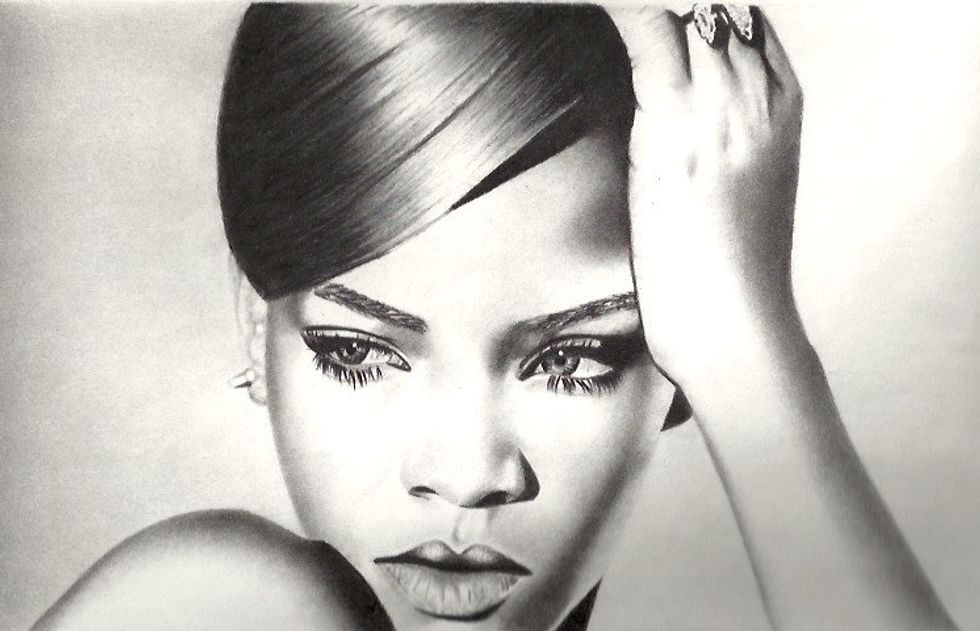

2. "Rihanna" by Gabriel S.

“Rihanna” by Gabriel S.

"Rihanna is who I got the most pictures of," von Furstenburg said. "I think it's because she is relatable in both her strength and her vulnerability. She's real.”

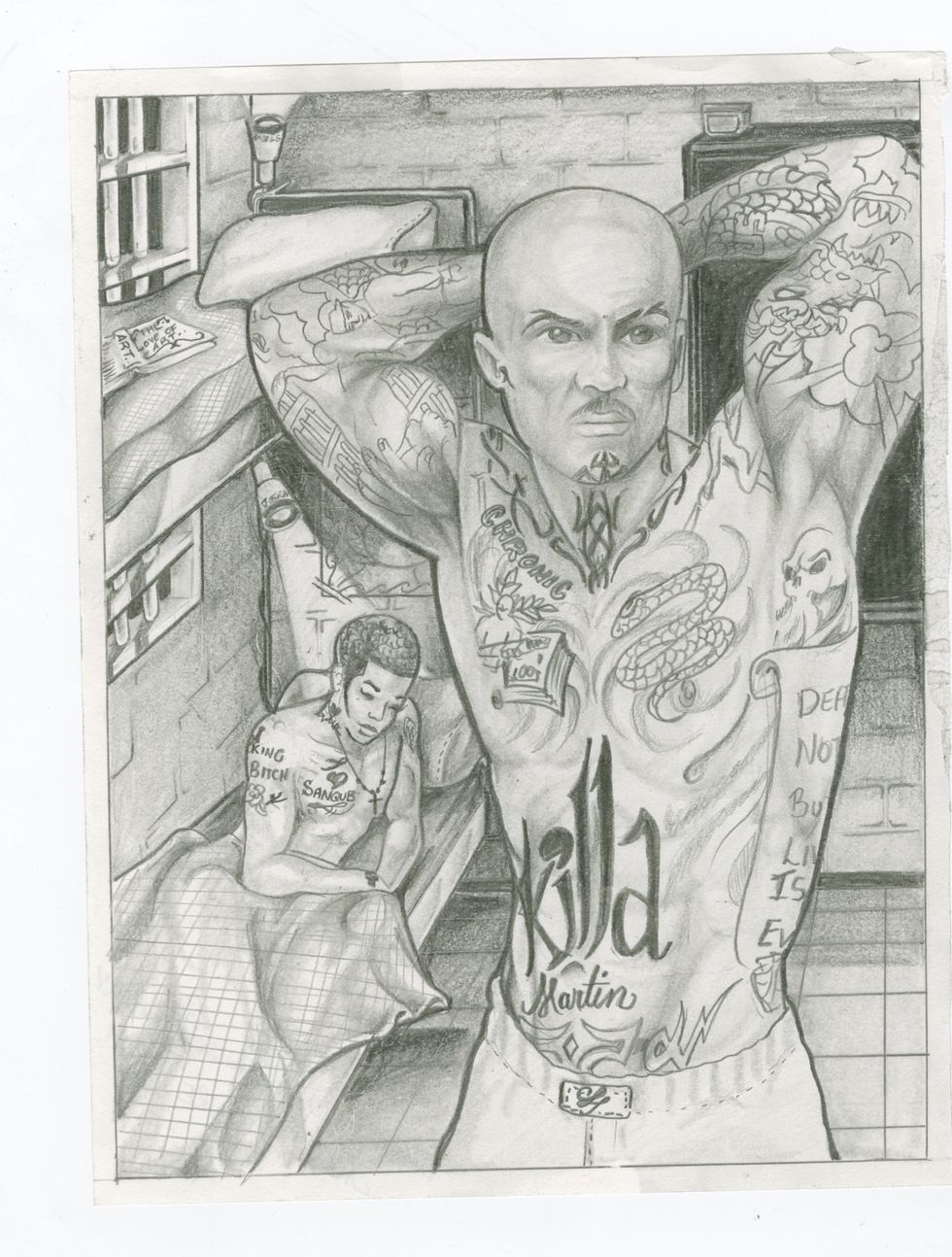

3. "Acceptance" by Stevie S.

"Acceptance" by Stevie S.

"This series is sexy and loving and domestic," von Furstenberg said about these two portraits by Stevie S. "A different look at family values/family portrait.”

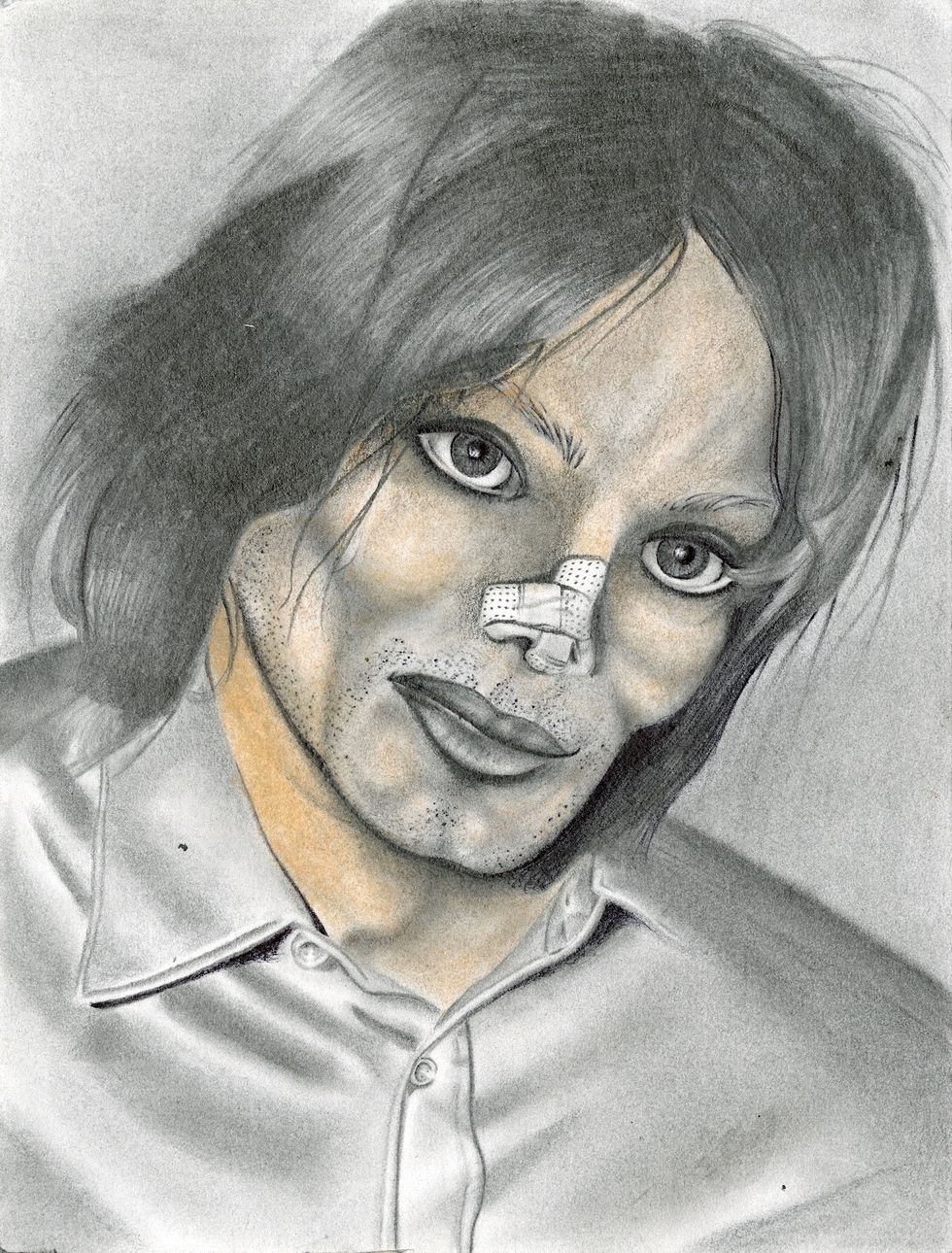

4. "Michael Jackson" by Jeremy M.

“Michael Jackson” by Jeremy M.

This was another one of von Furstenberg's favorites, because of the way it depicts a struggle with identity. "[MJ] was different, he was such a unique being that struggled so much with his identity and his body image the way a lot of our artists, especially our trans artists, are struggling behind bars," she said.

5. "Unknown" by Tiffany W.

“Unknown” by Tiffany W.

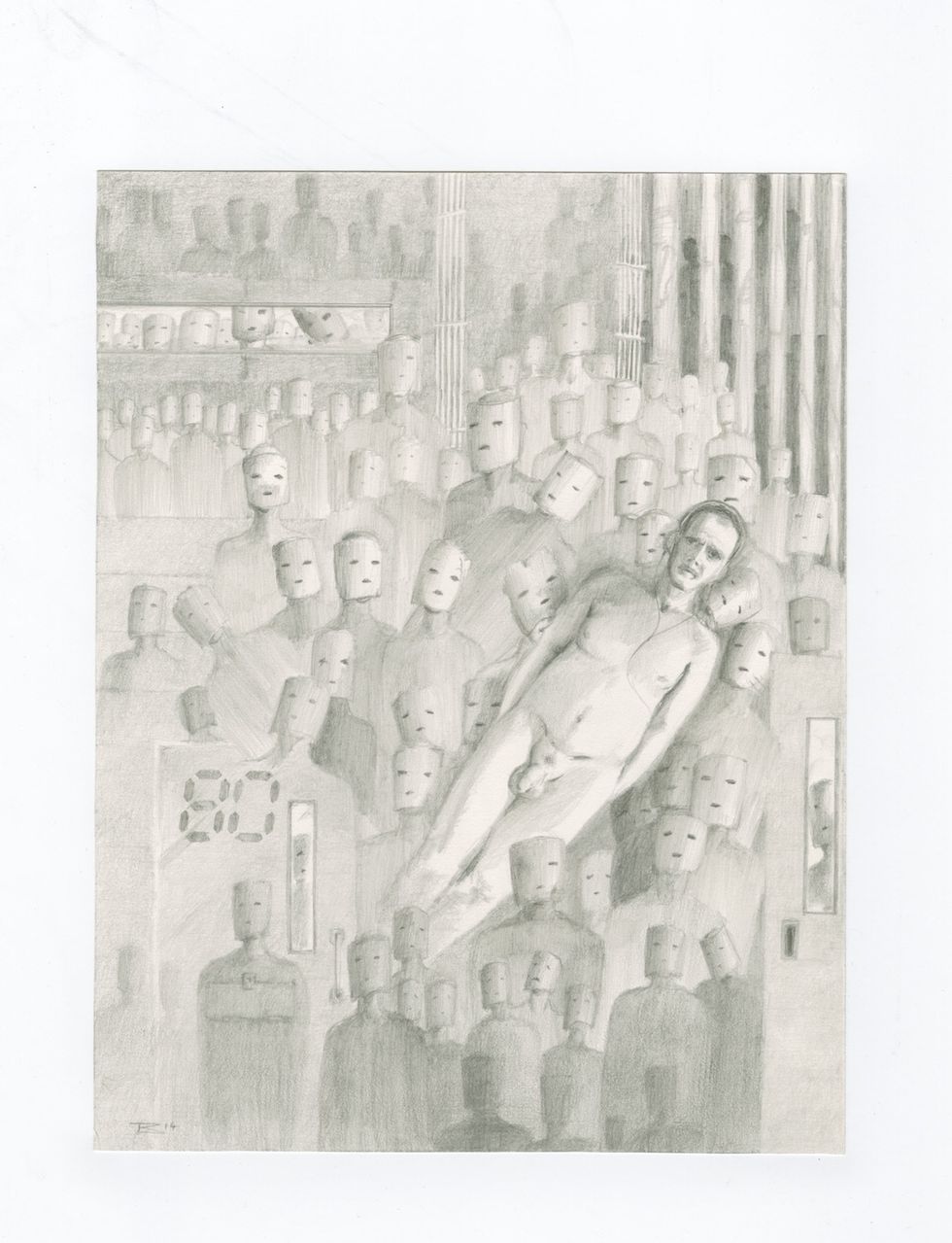

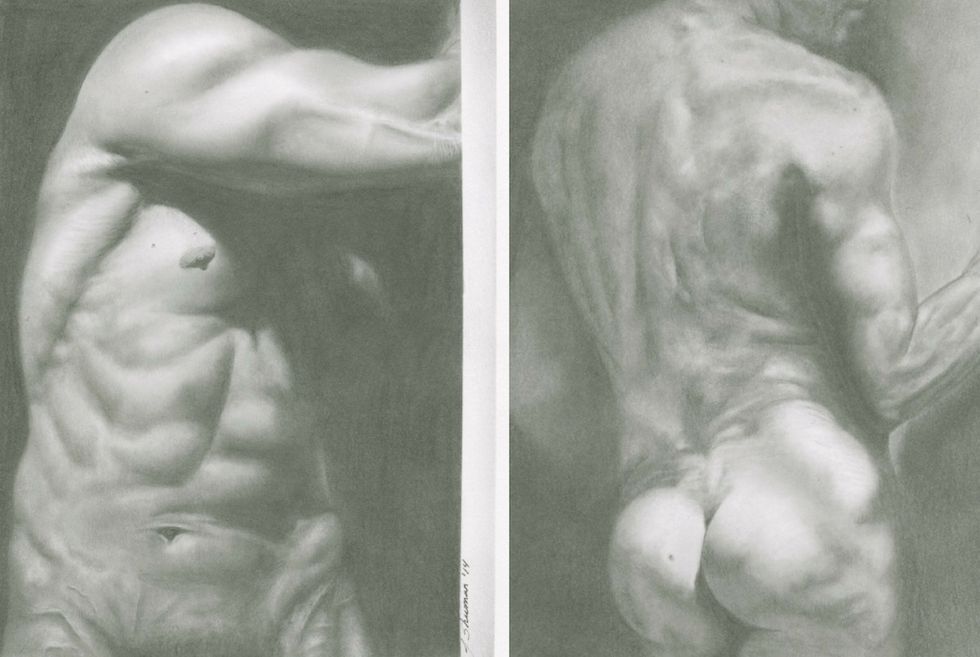

6. "Genotype" and "Life Study," by J.S.

“Genotype” and “Life Study” by J.S.

"This is the Michelangelo of the group," von Furstenberg said. "To be able to draw this with pencil and basic prison lighting is astounding. One of the best drawings I've ever seen in my life.”

When the exhibition opened to the public on Nov. 4, 2016, visitors even had the chance to share their thoughts with the artists.

The exhibit included an interactive feature that allowed people to text their comments and responses to the artist, which von Furstenberg then converted to physical paper and mailed to inmates.

Some of the messages included:

"I have had many long looks in the mirror like in your piece the beauty within us. I'm glad you can see your beautiful self smiling out. I see her too. Thank you."

"I am so wowed by your talent. You used paper, kool aid and an inhaler to draw a masterpiece. I feel lucky to have been able to see your work, and I know that other New Yorkers will feel the same. Keep creating."

"I've dreamed the same dreams. The barriers in your way are wrong. We will tear them down some day. Stay strong Dear."

Many people were also surprised at how good the artwork was — but they shouldn't have been.

Just because someone's spent time in prison doesn't mean they can't be a good person — or a talented artist. They're also being compensated for their artwork. While business transactions with incarcerated people are technically illegal, $50 donations have been made to each artist's commissary accounts to help them purchase food and other supplies.

"We're led to believe that people behind bars are dangerous, that we're safer without them, but it's not true," von Furstenberg said. "The fact that anybody would assume that [the art] would be anything less than phenomenal shows that there's this hierarchy: The artist is up on this pedestal, and other people marginalized people are looked down upon.”

Art has always been about connecting people. And for these incarcerated LGBTQ artists, that human connection is more important than ever.

Perhaps the only thing harder than being in prison is trying to integrate back into society — something that most LGBTQ people struggle with anyway. These are people who have already had difficulty expressing who they are on the inside and who are now hidden away from the world behind walls.

On the Inside's art show provided them a unique opportunity to have their voices heard — and hopefully, their individual messages are loud enough to resonate when they're on the outside too.

This article originally appeared on 11.14.16