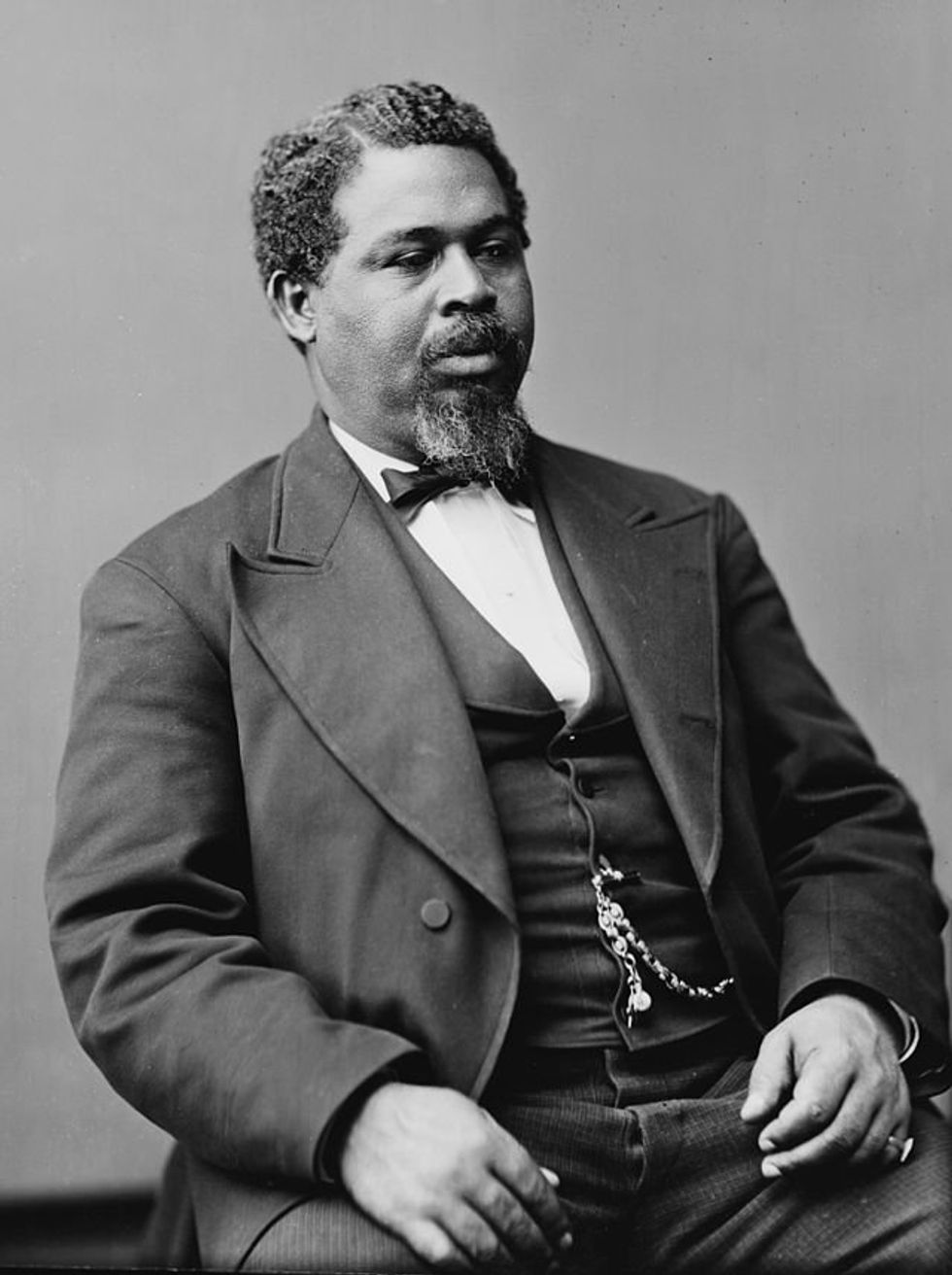

The enslaved man who stole a Confederate ship, sailed to freedom and became a U.S. Congressman

In a unanimous bipartisan move, South Carolina will honor Robert Smalls with the state's first statue of a Black American.

Robert Smalls led an extraordinary life.

South Carolina's statehouse boasts some two dozen statues honoring individuals from statesmen to "heroes" of the Confederacy, but there's a glaring omission from the lineup. Up until now, the former Confederate state—where the Civil War began at Fort Sumter and where approximately 1 in 4 residents is Black—has never erected an individual monument of a Black American.

In a unanimous bipartisan decision led by Republican Rep. Brandon Cox, Robert Smalls will become the first to be honored in this way, and his heroic life certainly earned him the accolade. As Cox told the Associated Press, "We’ve got a lot of history, good and bad. This is our good history."

Smalls was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1839. He and his mother lived together in a small cabin behind their enslaver's mansion until Smalls was sent to Charleston at age 12 to be hired out. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, he was in his early 20s and soon found himself an enslaved crewmember of a ship that was contracted out to the Confederate Army. There he was, an enslaved man sailing a steamboat for an army that was fighting to keep him enslaved.

Late one night, when the white crewmembers had all gone ashore, Smalls and the other enslaved crewmembers stole the ship with Smalls as pilot. They sailed to a wharf where they picked up their family members, then they made their way north. The sixteen enslaved people aboard managed to sail right on past Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie, where Confederate forces were stationed, thanks to Smalls donning a captain's hat and knowing the proper signals to give as they passed. He steered the ship to the naval blockade and turned the ship over to the U.S. Navy.

The enslaved crew and their families were now free Americans.

But Smalls didn't stop there. He provided valuable intelligence to the Union since he knew the Confederate waters well and served for the remainder of the war. He became the first Black person to serve as a pilot for the U.S. Navy and fought 17 Civil War battles as the captain of the very ship he has stolen.

His status as war hero was solidified. But he didn't stop there, either.

He returned to Beaufort in 1864 and used the reward money he's received from turning over the Confederate ship to buy the home of his former enslaver at a tax auction. In just three years, Smalls had gone from enslaved man to war hero and owner of his former owner's property.

And he became well known for it. He started his own business and advocated for public education. The people of Beaufort saw him as a leader and he began to rise politically. He served as a delegate to the State Constitutional Convention in 1868, then as a state representative, then state senator, then as a delegate to the Republican National Convention, and finally as a representative in the U.S. Congress.

He ended up serving five terms in the House of Representatives during the Reconstruction Era, when Black Americans voted in large numbers for the first time and were elected to government positions. According to the National Parks Service, Beaufort was viewed as a symbol of successful Reconstruction policies, with formerly enslaved people engaging in education, politics, and land ownership in the former Confederate county.

- YouTubeyoutu.be

However, the glory of that era didn't last as white Southerners regained political power. By the time Smalls died in 1915, segregation laws were widespread and the freedom that had been so hard won for Black Americans in the South had been curtailed. Even Smalls' incredible life story was largely forgotten by the "Lost Cause" rewriting of Civil War history.

However, the 21st century has seen historians setting the record straight and uplifting heroes like Robert Smalls who have not gotten the national recognition they deserve. After years of lobbying by the community of Beaufort to have Smalls and the reality of the Reconstruction Era recognized, January 2017, President Barack Obama issued an executive order establishing Reconstruction Era National Monument (now known as Reconstruction Era National Historical Park) in Beaufort County in January 2017.

And now South Carolina will erect a statue in Smalls' honor on the grounds of the statehouse. It's worth noting that the idea has been floated for years with bipartisan and biracial support, but had always faced some quiet opposition. Now it looks like everyone's on board, so it's just a matter of working out the exact design and location for the statue.

It's been a long time coming, but South Carolina is finally highlighting history we can all be proud of—a historic step in the right direction.