People 100 years ago died so much younger. 14 major reasons explain everything.

In 1796 we invented this amazing thing that could keep you from getting deadly diseases.

Lifespans were far shorter a century ago. Why?

Most of us know that human lifespans, overall, have gotten much longer. In the Middle Ages, the average life expectancy was a mere 31 years — though it's heavily skewed by the large number of people who died during childhood. Even still, a person living into their 80s or 90s was considered relatively rare.

One of the main reasons was that people at the time had little to no protection against disease.

That all started to change around 1796. That's when an English doctor named Edward Jenner took incredible risks to try to rid his world of smallpox, eventually creating an effective vaccine. It didn't become widely used for another several decades after that. Because of his efforts and the efforts of scientists like him, the only thing now standing between deadly diseases like the ones below and extinction are people who refuse to vaccinate their kids.

Unfortunately, because of the misinformation from the anti-vaccination movement, some of these diseases have trended up in a really bad way over the past several years.

Wellness involves a lot of personal choices and the tradeoff between personal liberty and shared public good.

Measles is the starkest example. In 2014, there were over 600 cases of measles in America during the first seven months of the year. According to the CDC, ten years later in 2024 there were 284 cases of measles nationwide. Though the numbers have improved in a decade, 89% of 2024's cases came from people who are unvaccinated or refused to share their vaccine status.

Anti-vaccination movements aren't new. Controversy, fear, and anti-vaccination rhetoric has plagued immunization efforts as far back as the early 1800s. Despite research conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) showing that vaccines and immunization research has had a positive impact on global health, the anti-vaccination movements don't seem to be facing eradication any time soon.

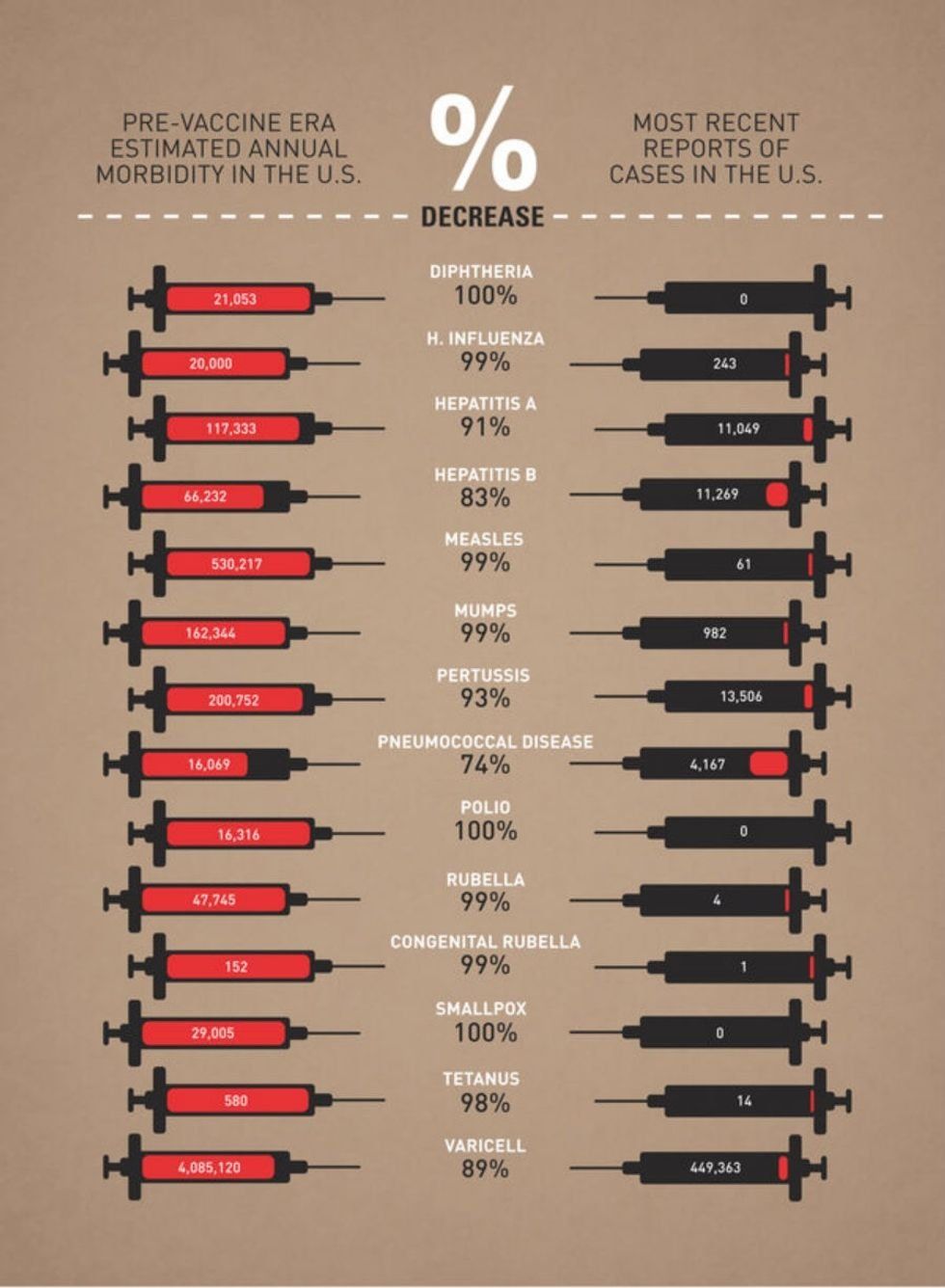

The chart below was made by graphic designer Leon Farrant and uses data from the CDC and JAMA to show that 14 major vaccines have real public health benefits.

Paired with decades of improved medical care, vaccines have nearly eradicated many formerly fatal illness like Polio, Measles, Malaria, and Diphtheria. The impact of one's personal health choices can have a significant impact on the population around them, in their communities, and even on a national level. It makes that trade-off all the more complicated and one not easily distilled into one convenient political or religious ideology.

Obviously, the topic of vaccinations has become immensely more complicated and controversial over the years, especially since the onset of COVID-19 in 2020. But history teaches us valuable lessons and information is power. No matter how you feel about vaccines today, this chart is a reminder that medical science can be used for incredible good. Without breakthrough vaccinations in the past, many of us would likely not be here to have the debate about our personal choices now and in the future.

This article originally appeared eleven years ago. It has been updated.

- Benjamin Franklin had to deal with smallpox anti-vaxxers. We can learn from his approach. ›

- Thrift store worker finds a polio vaccine card from 1956. Sure looks familiar, doesn't it? ›

- Why Matthew McConaughey's vaccination stance is causing a heated debate online ›

- Adults want vaccines to be administered the way these awesome doctors give shots to kids ›