The intriguing reason why people in the past looked a lot older than people today

Why did a 15 year old in 1960 look like they were 30?

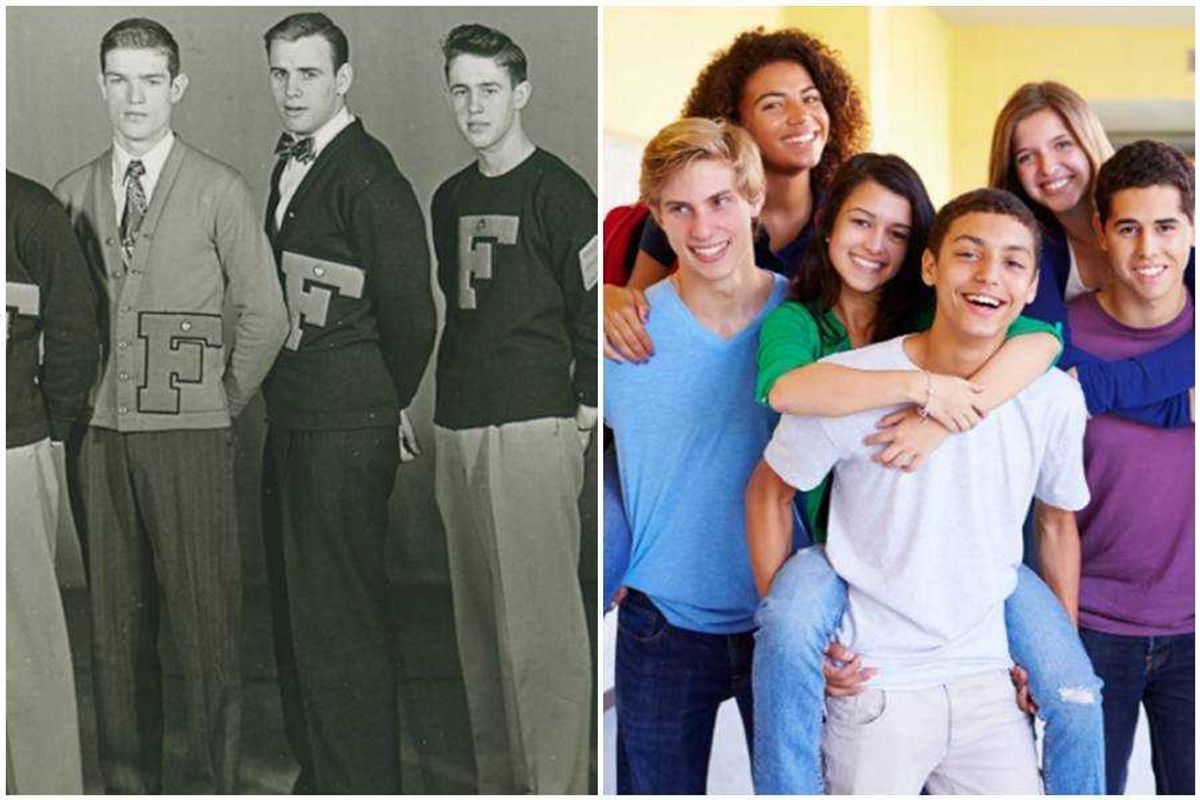

How are these both high schoolers?

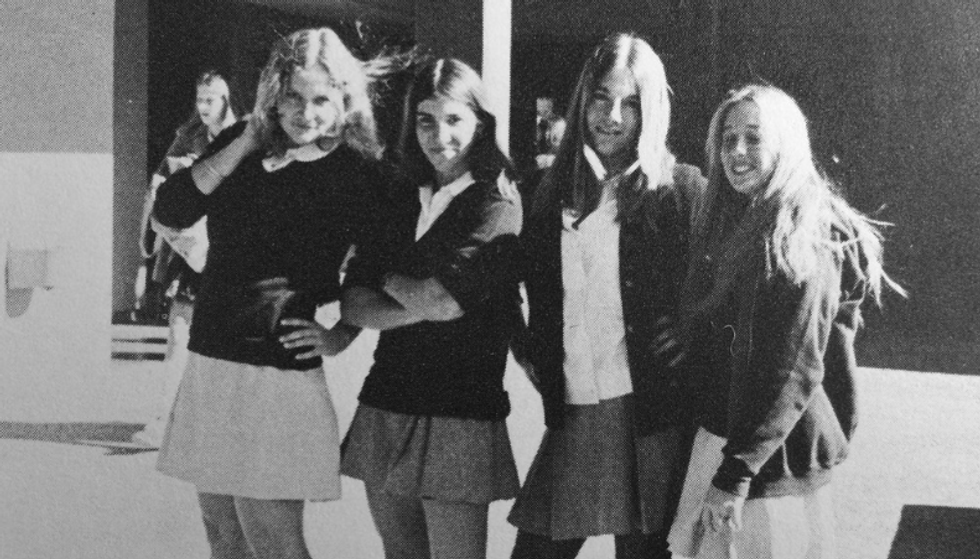

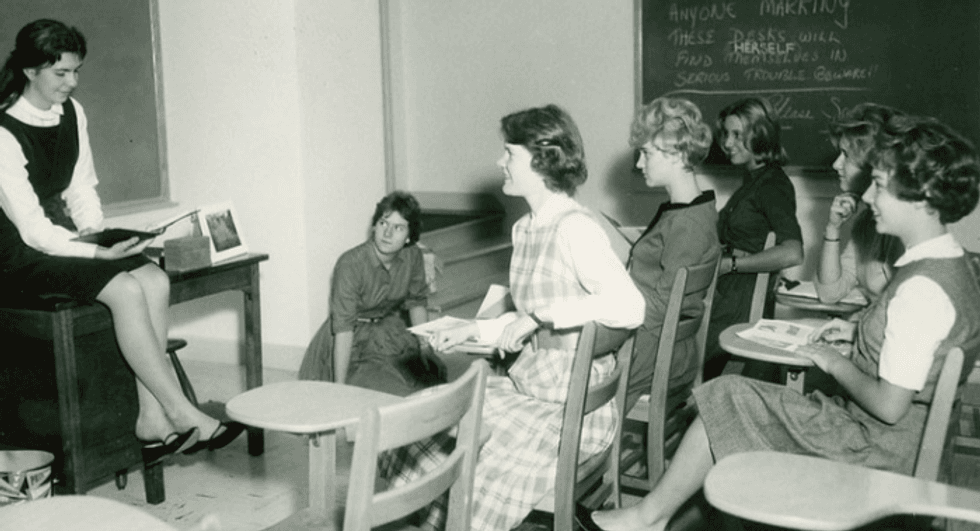

Have you ever looked back at your parents’ high school yearbook and thought that all the 11th graders looked like they were in their early 30s? Whether they were in school in the ‘60s and the kids had horn-rimmed glasses or the ‘80s with feathered hair, they looked at least a decade older than today's high school kids. One wonders if in 30 years, kids look at a yearbook from 2025 and see boys with broccoli cuts and girls with nose rings and they think, “What are they, 35?”

The folks at Bright Side did a deep dive into the phenomenon and found a few reasons why people looked so much older in the past than they do now. It’s a mix of how our minds perceive older fashion and why people age more gracefully in modern times.

Why did people look older in the past?

“Specialists have looked into this phenomenon, and it does have some scientific facts to back it up,” the narrator states. “It's not necessarily that our ancestors looked older; it's more that we appear to look younger. And younger as generations go by, that's because over time humans have improved the way they live their lives in the us alone over the last 200 years.”

- YouTube www.youtube.com

A big reason people looked much older when photography became common in the late 1800s is that it coincided with tremendous advances in public health. The 1880s to the 1920s were a time of rapid advancement, when we began to understand infectious diseases and how they spread. “We gained access after safer types of foods, and we understand the importance of clean water. Our individual lifestyle choices can impact the way we look,” the video says.

The way we work has also drastically changed how people look. Working in an office for eight hours a day in air conditioning will keep you a lot younger-looking than working all day as a Victorian chimney sweep. Plus, for people who work outside, sunscreen has made it much easier to protect our skin and decrease wrinkles.

Let’s not forget the importance of a straight, white smile. Advances in dental care also help make people look younger.

Why do people wearing styles from the past appear older?

Finally, there’s the clothes issue, and, yes, this does have a big impact on how we view the age of people from the past. “Our brains are wired to associate old trends with being old,” the video says. “For example, your grandpa might still have the shirt he wore in that 1970s picture, and it's because of that shirt that you retroactively associate that trend with being old, despite the fact that your granddad does look younger in the picture than he looks today. “

The interesting thing for people getting up in age is that if they want to appear younger, they have to be diligent about not wearing outdated styles, whether it's their makeup, hair, clothing, shoes, or how tight their jeans are. However, there's nothing that looks more foolish than a man in his 50s trying to dress like he's in his 20s, so what are we supposed to do? Humans are wired to figure out others' biological age, or how young they are, based on health cues, so instead of buying some new jeans, it may be better to hit the gym.

In the end, the fact that people look much younger today than they did in the past is a testament to how the quality of life has drastically improved since cameras were invented. However, that doesn’t mean that fashion has improved at all. You have to admit that your dad with that fly butterfly collar in his 1977 graduation photo looks better than that multi-colored, Machine Gun Kelly-style hoodie you see guys wearing in high schools today.

This article originally appeared in June.