Neuroscientists explain a fascinating phenomenon where people see faces as dragons

Alice in Wonderland syndrome continues to perplex experts.

A gray dragon statue.

As Halloween creeps ever closer, there's an interesting, yet scary brain phenomenon gaining attention that has neuroscientists a tad puzzled. Imagine this: You're talking to a neighbor and there's nothing out of the ordinary. Suddenly, their face gruesomely twists itself into something unrecognizable, morphing into—well, for lack of a better word—a demon or dragon face.

Also referred to as "Demon face syndrome," its medical name is prosopometamorphopsia (say THAT three times fast), and it was first coined by British neurologist MacDonald Critchley in 1953.

It sounds like something out of a horror film, but it's very real. In an 2014 study, four neuroscientists and psychologists—Dr. Jan Dirk Blom, PhDa, Iris E. C. Sommer, PhDc,d, Sanne Koops, MScc,d and the world-renowned Oliver W. Sacks, MDe—shared their case report in The Lancet Journal, entitled, "Prosopometamorphopsia and facial hallucinations." They discuss a 52-year-old woman who, in the midst of staring at a face, would experience something terrifying. "In just minutes, they (the faces) turned black, grew long, pointy ears and a protruding snout and displayed reptoid skin and huge eyes—bright, yellow, green, blue or red." This happened multiple times a day.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

Upon studying her case, they found she also experienced "occasional zoopsia," which is described as the sensation of "seeing large ants crawling over her hands." They say she was fully aware she was seeing hallucinations. In other words, she knew the phenomenon wasn't reality.

After looking at her blood test results and extensive neurological exams, they found very little out of the ordinary, other than some "white matter abnormalities." The condition is rare, but usually attributed to occipital lobe functioning (the part of the brain that controls visual perception) or, in some cases, tied in with "epilepsy, migraine or eye disease."

Years later, this complex disorder is still being discussed and diagnosed in a handful of studies—and it's still just as perplexing. In a recent article for Discover Magazine, writer Rosie McCall notes that the study was less about faces and more about being in the dark: “She saw similar dragon-like faces drifting towards her many times a day from the walls, electrical sockets, or the computer screen, in both the presence and absence of face-like patterns, and at night she saw many dragon-like faces in the dark.”

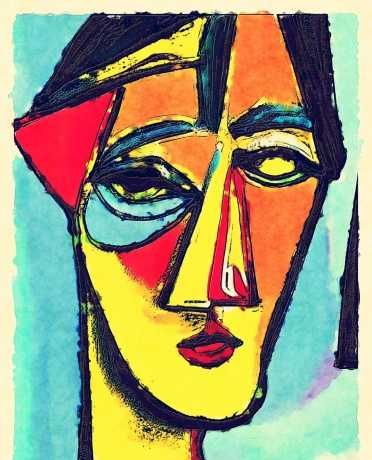

McCall shares, "Further examples of prosopometamorphopsia (specifically) include individuals who see faces transform into fish heads, faces melting, and faces featuring a third or fourth eye. It has even been put forward that the art of Pablo Picasso and Francis Bacon suggests they could have experienced the condition at some point in their lives."

Each step of learning about this is a jump down a new rabbit hole because prosopometamorphopsia happens to be part of a larger set of conditions called Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Those suffering from this condition might (for example) see only half a face, or perhaps faces and objects may appear larger or smaller than they are in actuality.

Also known as Todd syndrome, Mission Health reports: "For English psychiatrist John Todd, who named the condition in 1955—AIWS is a neurological disorder associated with a set of symptoms that affect how you perceive your body and the world around you."

In a video on SciShow Psych's YouTube channel, they make the distinction between people with this rare disorder and a drug-induced psychosis or a brain disorder like schizophrenia. "There's a key difference between these hallucinations and ones you'd experience for other reasons like drug use or schizophrenia. People with Alice in Wonderland syndrome always seem to KNOW they're illusions. They don't get confused about what's real and what's not."

- YouTube www.youtube.com

There are quite a few threads on Reddit dedicated to both PMO and its umbrella condition, Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Of the former, one Redditor shares a post writing, "A very rare condition known as prosopometamorphopsia (PMO) causes facial features to appear distorted. A new paper describes a 58-year-old male with PMO, who sees faces without any distortions when viewed on a screen and on paper but sees distorted faces that appear 'demonic' when viewed in-person."

Hundreds of comments follow, noting the connection to prosopagnosia (face blindness) and other conditions. One commenter shares, "There’s a guy on TikTok who has a schizophrenia diagnosis. He has a therapy dog who is trained to 'speak' (bark) if someone else is actually in the room with the guy. If no one else is in the room, the dog won’t bark. So when this guy has a hallucination that someone else is there, one of the first things he does is he commands his dog to 'speak.' If the dog doesn’t speak, then he knows he’s got a hallucination going."

Another adds, "I read about this through another source. 50% of the patients had lesions in their brain, meaning they had some sort of brain injury—seizures, fall, etc. Tinted colored glasses actually helped them stop seeing the distortions. One patient used a specific shade of green. Varies between patients."

As for Alice in Wonderland syndrome, another Redditor asked if anyone had it. Many confirm they did, and lots of commenters linked it to having migraines.

One person spun it in a positive light: "I didn't know it had this name until I was an adult. For me, I feel tiny and everything around me is giant and far away. It started as a kid, but I'm one of the people that never outgrew it. I still get it pretty frequently. Now I can control it to a point. I feel it and I can go in and out of the distortion as I want. It used to scare me but now I lean into the feeling because I like it."