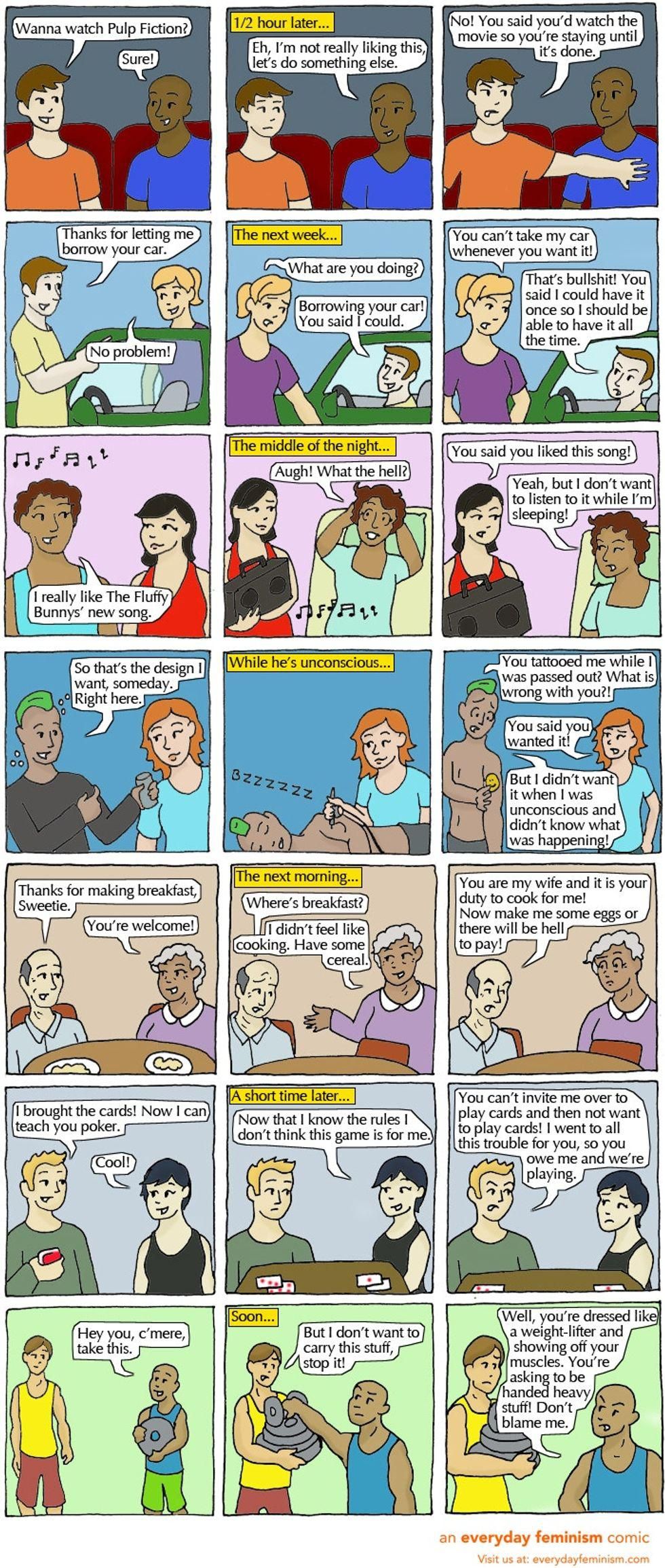

How 7 things that have nothing to do with rape perfectly illustrate the concept of consent.

Well this is all a very brilliant way to show what it's all about.

There are many different scenarios where consent is necessary.

In 2013, Zerlina Maxwell ignited a firestorm of controversy when she strongly recommended we stop telling women how to not get raped.

Here are her words, from the transcript of her appearance on Sean Hannity's show:

"I don't think that we should be telling women anything. I think we should be telling men not to rape women and start the conversation there with prevention."

So essentially—instead of teaching women how to avoid rape, let's raise boys specifically to not rape.

There was a lot of ire raised from that idea. Maxwell was on the receiving end of a deluge of online harassment and threats because of her ideas. The backlash was egregious, but sadly, it's nothing new. Such reactions are sadly common for outspoken women on the Internet.

People assumed it meant she was labeling all boys as potential rapists or that every man has a rape-monster he carries inside him unless we quell it from the beginning.

But the truth is most of the rapes women experience are perpetrated by people they know and trust. So, fully educating boys during their formative years about what constitutes consent and why it's important to practice explicitly asking for consent could potentially eradicate a large swath of acquaintance rape. It's not a condemnation on their character or gender, but an extra set of tools to help young men approach sex without damaging themselves or anyone else.

Zerlina Maxwell is interviewed on "Hannity."

Image from “Hannity."

But what does teaching boys about consent really look like in action?

Well, there's the viral letter I wrote to my teen titled "Son, It's Okay If You Don't Get Laid Tonight" explaining his responsibility in the matter. I wanted to show by example that Maxwell's words weren't about shaming or blaming boys who'd done nothing wrong yet, but about giving them a road map to navigate their sexual encounters ahead.

There are also rape prevention campaigns on many college campuses, aiming to reach young men right at the heart of where acquaintance rape is so prevalent. The 2014 movement, "It's On Us," was backed by The White House and widely welcomed by many young men.

And then there are creative endeavors to find the right metaphors and combination of words to get people to shake off their acceptance of cultural norms and see rape culture clearly.

This is brilliant:

A comic about different types of consent.

Image from Everyday Feminism, used with permission by creator Alli Kirkham.

There you have it. Seven comparisons that anyone can use to show how simple and logical the idea of consent really is. Consent culture is on its way because more and more people are sharing these ideas and getting people to think critically. How can we not share an idea whose time has come?

This article originally appeared ten years ago.