In the wake of yet another act of domestic terrorism, Donald Trump's proposed solution was not gun control, but "tackling the difficult issue of mental health."

He tweeted, “So many signs that the Florida shooter was mentally disturbed, even expelled from school for bad and erratic behavior."

I am not quoting this out of context. That was the clear angle of his comments on the matter — that this was an issue of one mentally ill individual, not cause for large-scale gun reform. It was a marked difference from his reactions to acts of terrorism committed by a brown Muslim man, wherein he called for immediate legislative action.

But that’s what mental illness is: the ultimate conversation killer.

Nothing makes people uncomfortable like the idea that the human brain is as vulnerable and fallible an organ as any other.

That’s why we like to make it sound like an anomaly — one that makes you immediately, inherently bad. We are attached to the idea that to have a flawed brain is to have a flawed character, mostly because it takes the work out of examining and interrogating our bad behavior. People who do bad things do them because they are crazy, we reason, not because they are people. The adversary is not our own flawed norms, but rather an individual outsider whose crimes are of an external origin.

According to Trump, the Parkland shooting didn’t happen because it's ridiculously easy to obtain an unconscionable range of lethal weaponry in this country. It’s not because we’ve fostered a culture where men feel powerful and entitled enough to exact violent revenge on others who have “wronged” them.

No, it's because the dude was “crazy.” Nothing to see here! Just another “deranged individual” who couldn’t possibly have been acting with a shred of his reality intact. We don’t share our reality with people like that, and theirs has nothing to do with ours — so the only problem, really, is that those kinds of people exist in the first place.

Society clings to the delusional idea that there is evil lurking in a brain merely because it is a brain that is different.

We’ve been vilifying mental illness for as long as we’ve been telling stories with villains in them. Where do all the bad guys in “Batman” go when they're caught? An asylum. The Joker was deemed insane, and poor Two Face was the smart and sensible Harvey Dent before injury and trauma rendered him “deranged.”

Some of the villains of “Harry Potter” are the Dementors, aka physical embodiments of depression. Of course, Voldemort himself was a bad apple from the start, the nonconsensual product of a love potion — never mind that more complicated bit about his being aided and abetted by the wizarding media and government. (Sound familiar?)

While it’s certainly true that there are mentally ill people who do bad things, we are also the heroes, the bystanders, the victims — the human beings who make up every part of every story.

1 in 25 adults lives with a serious mental illness (I'm one of them!), and 1 in 5 experience some form of mental illness like anxiety or depression in any given year. Only 3–5% of violent acts can be attributed to this huge portion of the U.S. population, yet neurodiverse people are 10 times more likely than their neurotypical counterparts to be victims of violence.

Anyone with a modicum of sense could tell you that the stereotype simply doesn’t add up.

The issue here has far less to do with mental illness than it has to do with the very human proclivity for violence, hate, and destruction.

Mentally ill people are certainly capable of such things, seeing as we are just as human as anyone else. But we're also capable of the equally human virtues of compassion, empathy, and creation — often in ways that are informed by our experiences living with and being marginalized because of mental illness.

And if we dig a little deeper than the “crazed” antagonists of popular culture, we can find mental illness woven between the lines of our heroes and saviors and all the normal people that fill up the gaps, no matter how convinced we may be that mental illness is monstrously abnormal.

We don’t talk about how Harry Potter’s PTSD made him a resilient and passionate agent for change. We forget Batman’s phobic origins and his many parallels to the Joker. Hannibal Lecter is what a certain beloved band might call a “psycho killer,” but Clarice and Will both serve as protagonists with far-from-typical neurologies of their own.

We struggle to see the diverse and deeply relatable experiences of mentally ill people already imprinted onto our stories because we only ever look for them when we’re trying to find someone to blame.

Mentally ill people are not separate from us — they are part of us.

1 in 25 people is about eight people in every full movie theater, three in every church congregation, and two in the average college classroom. Rarely are we the armed and murderous person who walks in and massacres all of those people. We are far more likely to kill ourselves than we are to kill another person. If there’s any mental health problem in this country, it’s a severe lack of accessible and affordable mental healthcare, which — last I checked — the Trump administration is actively seeking to make even more inaccessible.

Mentally ill people aren’t the problem. The people in power are — from Trump to the NRA to the “lone wolf” white male terrorists our sensationalist media encourages and excuses.

They're just pointing at us so that people will stop looking at them.

This article by Jenni Berrett originally appeared on Ravishly and has been republished with permission. More from Ravishly:

Student smiling in a classroom, working on a laptop.

Student smiling in a classroom, working on a laptop. Students focused and ready to learn in the classroom.

Students focused and ready to learn in the classroom.

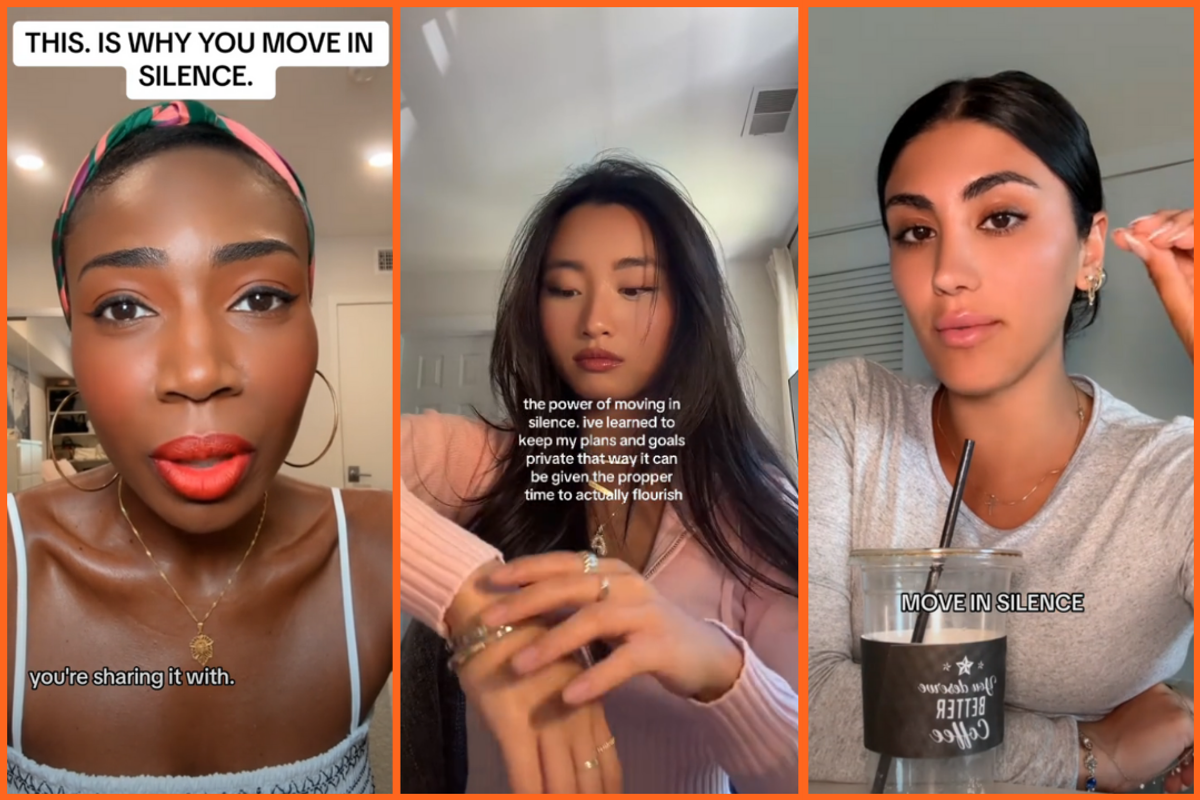

A woman telling you to be quiet.via

A woman telling you to be quiet.via  A woman telling you to be quiet.via

A woman telling you to be quiet.via

Fish find shelter for spawning in the nooks and crannies of wood.

Fish find shelter for spawning in the nooks and crannies of wood.  Many of these streams are now unreachable by road, which is why helicopters are used.

Many of these streams are now unreachable by road, which is why helicopters are used. Tribal leaders gathered by the Little Naches River for a ceremony and prayer.

Tribal leaders gathered by the Little Naches River for a ceremony and prayer.

A man standing up inside a plane

A man standing up inside a plane A hospice nurse with her female patient.

A hospice nurse with her female patient.

Can't quite imagine this on the average American school lunch tray.

Can't quite imagine this on the average American school lunch tray. A typical American school lunch.

A typical American school lunch. Kids eating lunch.

Kids eating lunch.