The very real story of how one woman prevented a national tragedy by doing her job

Frances Oldham Kelsey believed thorough research saves lives. She was so right.

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey and President John F. Kennedy.

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey had only been with the Food and Drug Administration for about a month when she was tasked with reviewing a drug named Thalidomide for distribution in America.

Marketed as a sedative for pregnant women, thalidomide was already available in Canada, Germany, and several African countries.

It could have been a very simple approval. But for Kelsey, something didn't sit right. There were no tests showing thalidomide was safe for human use, particularly during pregnancy.

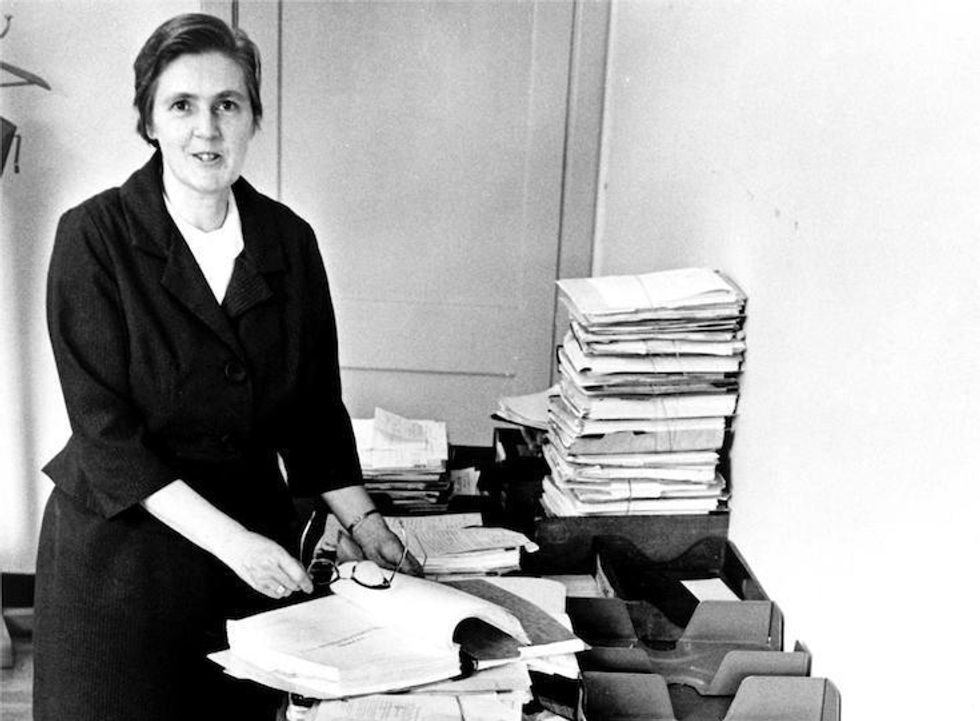

Kelsey in her office at the FDA in 1960.

Image by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

When pharmaceutical company Chemie Grünenthal released thalidomide in West Germany years earlier, they called it a "wonder drug" for pregnant women. They promised it would treat anxiety, insomnia, tension, and morning sickness and help pregnant women sleep.

What they didn't advertise were its side effects. Because it crosses the placental barrier between fetus and mother, thalidomide causes devastating—often fatal—physical defects. During the five years it was on the market, an estimated 10,000 babies globally were born with thalidomide-caused defects. Only about 60% lived past their first birthday.

In 1961, the health effects of thalidomide weren't well-known. Only a few studies in the U.K. and Germany were starting to connect the dots between babies born with physical defects and the medication their mothers had taken while pregnant.

At the outset, that wasn't what concerned Kelsey. She'd looked at the testimonials in the submission and found them "too glowing for the support in the way of clinical back up." She pressed the American manufacturer, Cincinnati's William S. Merrell Company, to share research on how their drug affected human patients. They refused. Instead, they complained to her superiors for holding up the approval. Still, she refused to back down.

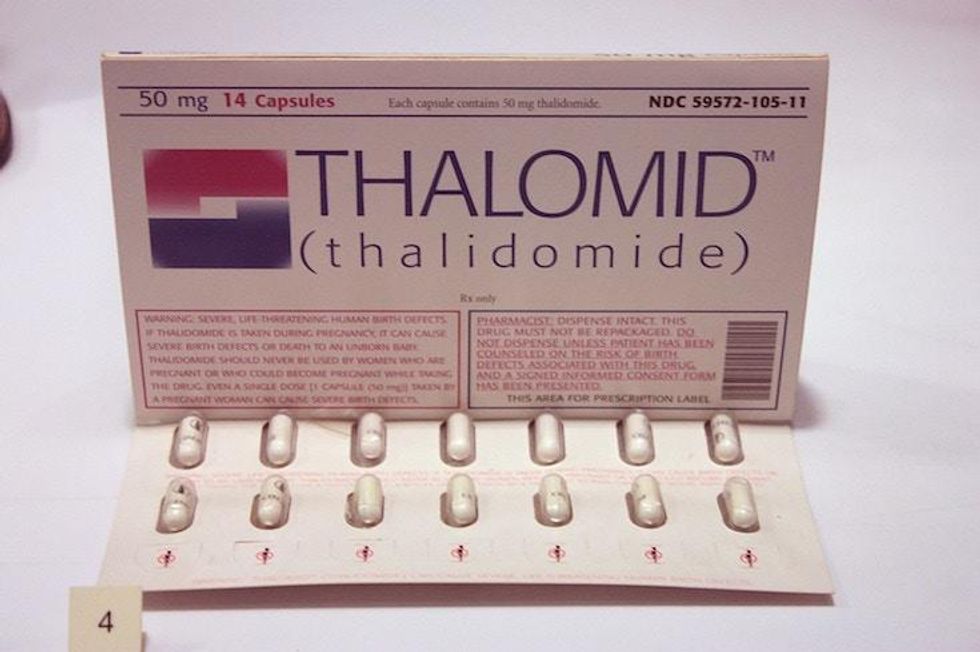

A sample pack of thalidomide sent to doctors in the U.K. While more than 10,000 babies worldwide were born with thalidomide-related birth defects, FDA historian John Swann credits Dr. Kelsey with limiting the number of American babies affected to just 17.

Image by Stephen C. Dickson/Wikimedia Commons.

Over the next year, the manufacturer would resubmit its application to sell thalidomide six times. Each time, Kelsey asked for more research. Each time, they refused.

By 1961, thousands of mothers were giving birth to babies with shocking and heartbreaking birth defects. Taking thalidomide early in their pregnancy was the one thing connecting them. The drug was quickly pulled from shelves, vanishing mostly by 1962.

Through dogged persistence, Kelsey and her team had prevented a national tragedy.

Kelsey joins President John F. Kennedy at the signing of a new bill expanding the authority of the FDA in 1962.

Image by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy honored Kelsey with the Federal Civilian Service Medal. He thanked her for her exceptional judgment and for preventing a major tragedy of birth deformities in the United States:

“I know that we are all most indebted to Dr. Kelsey. The relationship and the hopes that all of us have for our children, I think, indicate to Dr. Kelsey, I am sure, how important her work is and those who labor with her to protect our families. So, Doctor, I know you know how much the country appreciates what you have done."

But, she wasn't done yet. Later that year, the FDA approved new, tougher regulations for companies seeking drug approval, inspired in large part by Kelsey's work on thalidomide.

Reached via email, FDA historian John Swann said this about Kelsey's legacy: "[Her] actions also made abundantly clear to the nation the important public health role that drug regulation and FDA itself play in public health. The revelation of the global experience with that drug and America's close call indeed provided impetus to secure passage of a comprehensive drug regulation bill that had been more or less floundering during the time FDA was considering the application."

Kelsey continued to work for the FDA until 2005. She died in 2015, aged 101, just days after receiving the Order of Canada for her work on thalidomide.

Bureaucratic approval work is rarely thrilling and not often celebrated. That's a shame because it's so critical.

People like Kelsey, who place public health and safety above all else — including their career — deserve every ounce of our collective respect and admiration.

This story originally appeared nine years ago.

A Generation Jones teenager poses in her room.Image via Wikmedia Commons

A Generation Jones teenager poses in her room.Image via Wikmedia Commons

An office kitchen.via

An office kitchen.via  An angry man eating spaghetti.via

An angry man eating spaghetti.via

An Irish woman went to the doctor for a routine eye exam. She left with bright neon green eyes.

It's not easy seeing green.

Did she get superpowers?

Going to the eye doctor can be a hassle and a pain. It's not just the routine issues and inconveniences that come along when making a doctor appointment, but sometimes the various devices being used to check your eyes' health feel invasive and uncomfortable. But at least at the end of the appointment, most of us don't look like we're turning into The Incredible Hulk. That wasn't the case for one Irish woman.

Photographer Margerita B. Wargola was just going in for a routine eye exam at the hospital but ended up leaving with her eyes a shocking, bright neon green.

At the doctor's office, the nurse practitioner was prepping Wargola for a test with a machine that Wargola had experienced before. Before the test started, Wargola presumed the nurse had dropped some saline into her eyes, as they were feeling dry. After she blinked, everything went yellow.

Wargola and the nurse initially panicked. Neither knew what was going on as Wargola suddenly had yellow vision and radioactive-looking green eyes. After the initial shock, both realized the issue: the nurse forgot to ask Wargola to remove her contact lenses before putting contrast drops in her eyes for the exam. Wargola and the nurse quickly removed the lenses from her eyes and washed them thoroughly with saline. Fortunately, Wargola's eyes were unharmed. Unfortunately, her contacts were permanently stained and she didn't bring a spare pair.

- YouTube youtube.com

Since she has poor vision, Wargola was forced to drive herself home after the eye exam wearing the neon-green contact lenses that make her look like a member of the Green Lantern Corps. She couldn't help but laugh at her predicament and recorded a video explaining it all on social media. Since then, her video has sparked a couple Reddit threads and collected a bunch of comments on Instagram:

“But the REAL question is: do you now have X-Ray vision?”

“You can just say you're a superhero.”

“I would make a few stops on the way home just to freak some people out!”

“I would have lived it up! Grab a coffee, do grocery shopping, walk around a shopping center.”

“This one would pair well with that girl who ate something with turmeric with her invisalign on and walked around Paris smiling at people with seemingly BRIGHT YELLOW TEETH.”

“I would save those for fancy special occasions! WOW!”

“Every time I'd stop I'd turn slowly and stare at the person in the car next to me.”

“Keep them. Tell people what to do. They’ll do your bidding.”

In a follow-up Instagram video, Wargola showed her followers that she was safe at home with normal eyes, showing that the damaged contact lenses were so stained that they turned the saline solution in her contacts case into a bright Gatorade yellow. She wasn't mad at the nurse and, in fact, plans on keeping the lenses to wear on St. Patrick's Day or some other special occasion.

While no harm was done and a good laugh was had, it's still best for doctors, nurses, and patients alike to double-check and ask or tell if contact lenses are being worn before each eye test. If not, there might be more than ultra-green eyes to worry about.