The 1776 Report is rife with 'errors, distortions, and outright lies' say historians

The 1776 Report isn't just bad, it's historically bad, in every way possible.

When journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones published her Pulitzer Prize-winning 1619 Project for The New York Times, some backlash was inevitable. Instead of telling the story of America's creation through the eyes of the colonial architects of our system of government, Hannah-Jones retold it through the eyes of the enslaved Africans who were forced to help build the nation without reaping the benefits of democracy. Though a couple of historical inaccuracies have had to be clarified and corrected, the 1619 Project is groundbreaking, in that it helps give voice to a history that has long been overlooked and underrepresented in our education system.

The 1776 Report, in turn, is a blaring call to return to the whitewashed curriculums that silence that voice.

In September of last year, President Trump blasted the 1619 Project, which he called "toxic propaganda" and "ideological poison" that "will destroy our country." He subsequently created a commission to tell the story of America's founding the way he wanted it told—in the form of a "patriotic education" with all of the dog whistles that that phrase entails.

Mission accomplished, sort of.

The 1776 Report from the commission was released yesterday, and historians have near-universally panned it as an ahistorical piece of political propaganda—and a poorly constructed one at that. (You can read the report here.)

Even just a cursory glance at the table of contents is a clue to the what-the-what foolishness we're going to find within it.

The introduction to the report states that the 1776 Commission is "comprised of some of America's most distinguished scholars and historians" and calls the report "a definitive chronicle of the American founding, a powerful description of the effect the principles of the Declaration of Independence have had on this Nation's history, and a dispositive rebuttal of reckless 're-education' attempts that seek to reframe American history around the idea that the United States is not an exceptional country but an evil one."

The first problem is that these "distinguished scholars and historians" don't include a single actual American historian among them. There are a couple of people whose scholarship fields—namely political science and classicism—are somewhat tangentially related to the topic, but if you're really trying to write a "definitive chronicle of the American founding," it would probably be good to include some actual experts in American history.

Of course, there's a good reason that they didn't include American historians—because finding an actual American historian to sign onto such a distorted representation of history is darn near impossible. It might also be because actual historians generally do their research work through universities, which the report criticizes as "hotbeds of anti-Americanism, libel, and censorship that combine to generate in students and in the broader culture at the very least disdain and at worst outright hatred for this country."

David W. Blight, Professor of History, of African American Studies, and American Studies at Yale, calls the report "beliefs devoid of history," a "puerile, politically reactionary document," and "the final desperate act of MAGA functionaries" which "needs a janitor's broom."

He also wrote that the report "may end up anthologized someday in a collection of fascist and authoritarian propaganda," a sentiment shared by Stanford PhD student Austin Clements, whose studies focus on fascism and the Far Right.

Heather Cox Richardson, an American historian from Boston College who has grown a huge following for her daily documentation of American history in real-time, wrote of the report: "Made up of astonishingly bad history, this document will not stand as anything other than an artifact of Trump's hatred of today's progressives and his desperate attempt to wrench American history into the mythology he and his supporters promote so fervently."

Even Steven Wilentz, a Yale historian who has criticized the 1619 Project, told the Washington Post that the 1776 Project is nothing more than political commentary. "It reduces history to hero worship," he wrote in an email. "It's the flip side of those polemics, presented as history, that charge the nation was founded as a slavocracy, and that slavery and white supremacy are the essential themes of American history. It's basically a political document, not history."

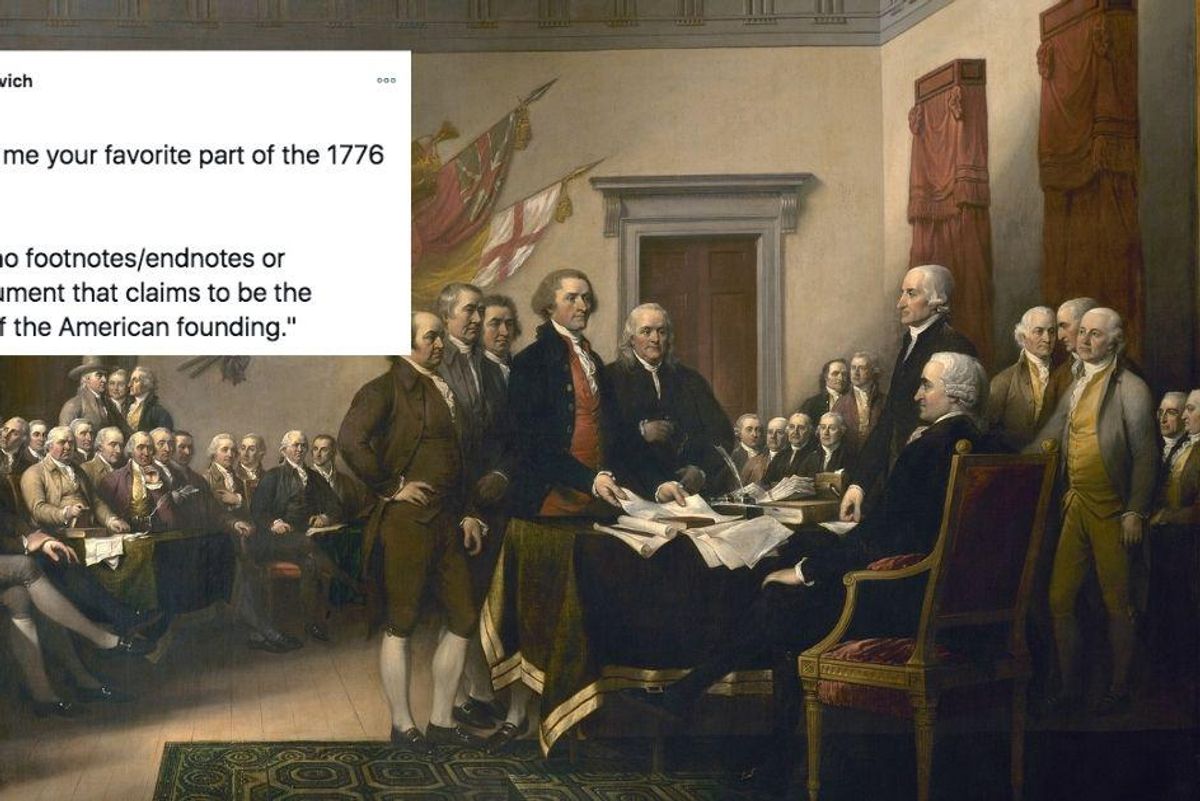

Professor Jacqueline Antonovich asked historians on Twitter to share their "favorite" part of the report and kicked off the parade by pointing out that there are no citations—no footnote, endnotes, or bibliography—to be found. A high school history paper would be flunked for such an omission.

Columbia history professor, Dr. Karl Jacoby, pointed out that the document lavishes praise on the Declaration of Independence (indeed, it's a primary focus of the report) but totally ignores the fact that it calls Indigenous people "merciless Indian savages." As a matter of fact, Indigenous people basically don't exist in this telling of America's founding.

Eric Rauchway, history professor at the University of California at Davis, told the Washington Post, "It's very hard to find anything in here that stands as a historical claim, or as the work of a historian. Almost everything in it is wrong, just as a matter of fact. I may sound a little incoherent when trying to speak of this, because the report itself is not coherent. It's like historical whack-a-mole."

One of the criticisms of progressivism in the report is what it refers to as a post-Civil Rights Movement focus on "group rights." However, Rauchway recalls the formation of the Senate as an example of group rights that long predates modern sensibilities. "Group rights is not anathema to American principles," he told the Post. "Why do Wyomingers have 80 times the representation that Californians have if not for group rights?"

The way both slavery and the post-Civil Rights Movement era are treated is mind-bogglingly distorted, as Ibram X. Kendi points out.

He also points out the inherent problem with the "Black people have been given preferential treatment for decades" argument, which logically leads to the racist idea that since disparities still exist, Black people must just be inferior.

One of the worst aspects of the report is that it was released on MLK Day,

The problem is that this report will undoubtedly be used by some as the foundation for American education, ignoring the irony that it's a blatantly biased propaganda document that decries teaching "one-sided," "activist propaganda."

Nikole Hanna-Jones has said that she wanted to write the 1619 Project and its accompanying curriculum to get kids to ask questions. Historian Kevin Levin points out that the 1776 Report appears to have the opposite focus, viewing "students as sponges who are expected to absorb a narrative of the American past without question. It views history as set in stone rather than something that needs to be analyzed and interpreted by students."

And as writer Michael Harriot pointed out, the report is merely a return to the whitewashed history students were taught for generations, putting the founding fathers up on a pedestal from which they could do no real wrong and glossing over the problematic elements of our history that still have lingering effects today.

A nuanced approach to American history is vital, as is acknowledging that two things can be true at the same time. The democratic principles laid out in the founding documents of our nation are exceptional and deserving of praise and the U.S. has yet to truly live up to the ideals they espouse. It is in no way unAmerican or anti-American to be honest and forthright about America's past and current sins and to strive to form a more perfect union by working toward true liberty and justice for all. Equating a desire to better understand the vast, ongoing impact of historical injustices in our country with "hatred for America" is simplistic and untrue. It's not only possible to love America and want her to be better, it's actually a sign of loving America to examine her past fully, to assess her present truthfully, and to imagine her future hopefully.

To pretend that the U.S. is and has always been perfect is an insult to the millions who have suffered at her hands, and this report is an insult to the millions who understand that. Whitewashing history in the name of "patriotic education" is not virtuous. It never has been and it certainly never will be.

- This is roughly 200 years of American history in one mesmerizing GIF. ›

- A historian accidentally discovered how our history textbooks openly ... ›

- Sally Hemings is part of American history. The Jefferson estate is ... ›

- 'The Tiffany Problem' explains false anachronisms in stories - Upworthy ›