Weird but true history: Why the calendar skipped from October 4th to the 15th in 1582

Those 10 days simply don't exist…sort of.

The switch to the Gregorian calendar messed up our measurement of time for a bit there.

If you think crossing time zones and navigating Daylight Savings Time can be confusing, imagine losing or gaining multiple days just by crossing a border.

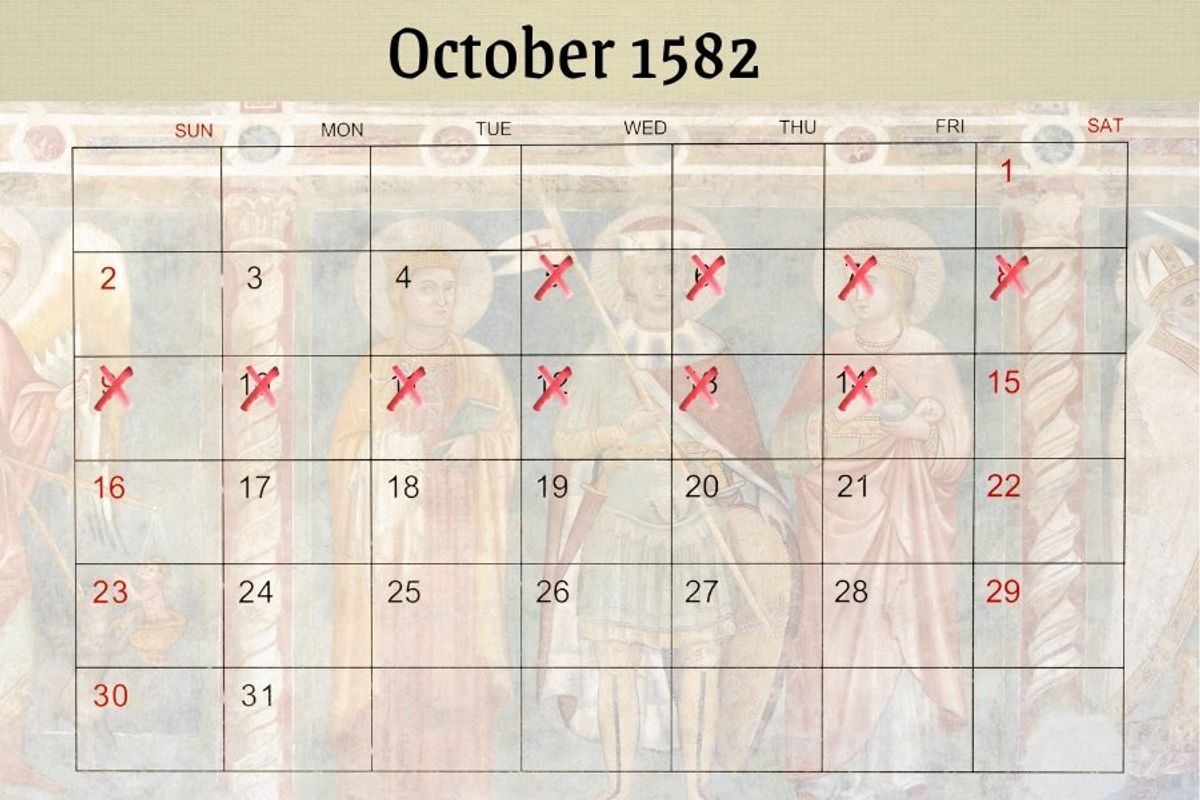

That was life for Europeans in the late 16th century after 10 days were eliminated from the Gregorian calendar. In 1582, if you lived in a Catholic country, the calendar went from October 4 to October 15—the dates in between just didn't exist. As a result, you could find yourself going back or forward in time simply by entering or exiting a non-Catholic country.

What happened to the missing 10 days in October of 1582?

The mystery of the missing days isn't so much a mystery as a miscalculation. For nearly 1,600 years, the Julian calendar had been used by people across Europe, and on the surface it wasn't a whole lot different than the Gregorian calendar we use today—365 days in a year with a leap year every 4 years and the spring equinox being placed on March 21.

But there was one problem: It was off on how long a solar year is by 11 minutes and 14 seconds.

That may not seem like much, but after over 1,000 years, it added up. Placing a leap year every four years without exception meant that the equinox was slowly pushed back on the calendar. By the mid-1500s, the equinox fell on March 11 instead of March 21. As a result, the calculations for Easter were thrown off.

How the Gregorian calendar recalibrated the spring equinox

After years of consultations among church leaders about how to fix the problem, Pope Gregory XIII signed an edict implementing a new calendar system—the Gregorian calendar we use today—in February of 1582. As part of the implementation, 10 days were removed from October during weeks that wouldn't affect any of the Christian holidays to get the equinox back to March 21.

But losing those days wasn't seamless. For one, since the change came from the pope, non-Catholic countries weren't too keen on taking up the new calendar. Austria, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Poland, and the Catholic states of Germany switched to the Gregorian calendar, but Protestant and Orthodox countries of Europe resisted. They all came around eventually, but it took more than 100 years for the British Empire to jump on board, and some countries, including Russia, Turkey, Greece, Albania, Lithuania, and Estonia, didn't make the switch until the 20th century.

In the meantime, the removal of October 5 to 14 meant that dates were different in different countries—and in some cases even within the same country. Germany was split by Catholic and Protestant regions, so the two different calendars made travel between those regions really weird date-wise. (Imagine trying to navigate that kind of chaos in today's global neighborhood. Good thing they didn't have airplanes then.)

Leap year calculations in the Gregorian calendar are a little more complicated

Now, one might ask, "If the Julian calendar had a leap year every four years, didn't that account for the length of time in a solar year? How is that different than the leap years we have in the Gregorian calendar?"

The answer is that the way leap years work in the Gregorian calendar is a bit more complex than many of us realize. Most of us were taught that we have a leap year every four years, which is generally true, but with some regularly scheduled exceptions. We don't hear about these exceptions because they happen so infrequently and won't happen within our lifetime, but they make all the difference mathematically.

In the Gregorian calendar, we add a day to the calendar (February 29th) every four years except on years that can be divided by 100, which are not leap years, unless the year can also be divided by 400, in which case it is a leap year. That might sound confusing, but essentially, 1700, 1800, 1900 were not leap years, but 2000 was. The years 2100, 2200 and 2300 will not be leap years, but 2400 will be.

Removing those leap years every 100 years but not every 400 years accounts for the miscalculation in the Julian calendar, just as removing the 10 days from October of 1582 fixed the drift that had occured over millennia because of it. There are still different calendars used in different places for different purposes, but the Gregorian calendar has gradually become the international standard for dates and times.

Time may be a construct, but humans have managed to construct quite a detailed system of measuring it, even with some quirky bumps along the way.