Young refugees found a creative way to spread information about Coronavirus in their settlement.

Songs have a habit of getting stuck in your head — especially ones you like. They can be powerful ways to spread — and remember — important information. (Remember when you learned your ABC's through song in Kindergarten?)

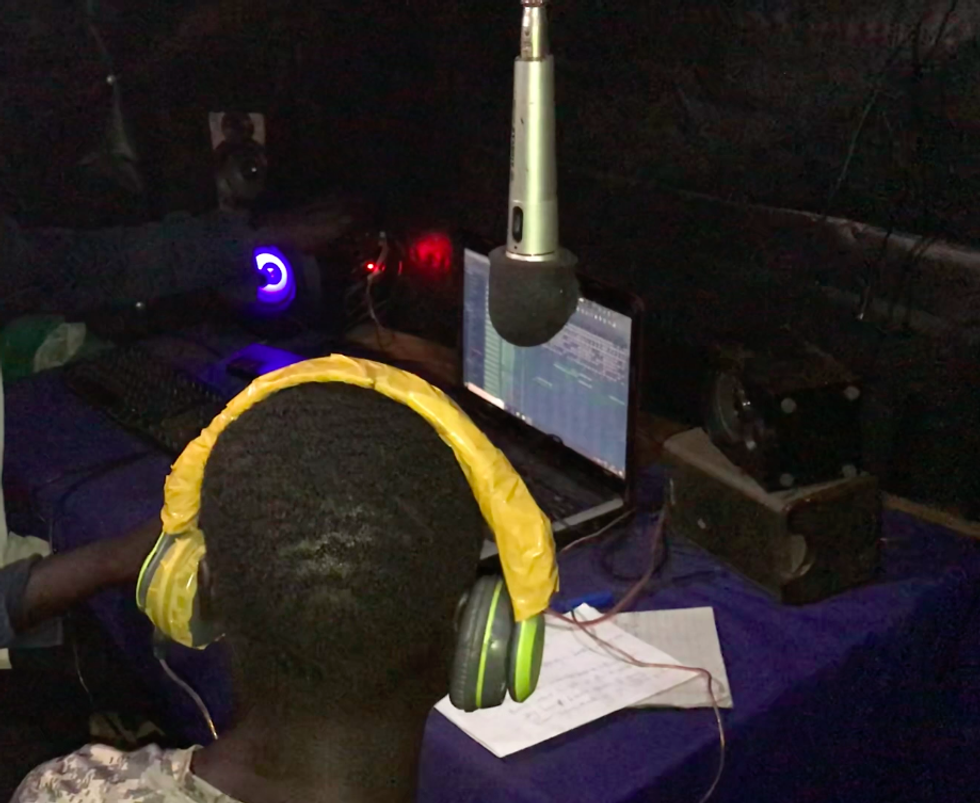

That's why at Bidi Bidi refugee settlement in Uganda, some young people are using their creativity to raise awareness about the coronavirus by writing songs about it.

"For months now, awareness campaigns have been created," says David, a teenager who lives in the settlement. "These include posters, radio messages and public messages." World Vision Uganda, for example, has been going door to door to drive awareness in settlements, using mobile public address systems and megaphones.

But young people like David in the settlement are taking things one step further: they're recording the songs and sharing the music at food distribution points so everyone hears their messages. For them, music is not only a creative outlet: it is also a powerful way to engage with and protect their vulnerable community from this deadly disease.

"Children and young people are amazing. We see time and again, all over the world, they are not helpless, hidden victims. So often in a crisis, they are hidden heroes," says Dana Buzducea, World Vision's Global Head of Advocacy.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 7.9 million people around the world have caught COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. As of June 16th, the disease had killed 434,796 worldwide. 181,903 of these cases were in Africa; 823 of those were in Uganda where the Bidi Bidi refugee settlement is located.

People and children living in refugee settlements, like this one, might be particularly at risk for COVID-19.

There are 1.4 million refugees in Uganda with the majority having fled a civil war in South Sudan. 270,000 of those refugees live in Bidi Bidi Refugee camp; more than half are children. Many became separated from their parents when they fled the conflict and have had to learn to take care of themselves. Others might have a grandparent with them — but since COVID-19 is particularly deadly to elderly adults, they're also now at risk of being alone if the virus takes hold in the camp.

This is why in March, World Vision asked that countries hosting high numbers of refugees, such as Uganda, be given special and urgent support because of the potential impact of the disease, both directly and indirectly.

"The disease might not kill as many children from the available statistics but the impact on them is great," Brenda Madrara, project manager at World Vision, said in a recent article. "In our foster programme, we train and facilitate foster parents to take care of these vulnerable children. This is now difficult because everyone is scared and they only want to take care of their own, without any extra responsibility."

In other words, because of the lockdown, money, food and other resources are already stretched thin. Bringing in a child to care for — especially one that might be infected — is scary.

This is the reason it's so important to prevent the rapid spread of the virus in these settlements. World Vision is currently working with The Office of the Prime Minister to respond to the urgent needs to help stop the spread of the virus, such as soap, hand washing facilities and personal protective equipment for health workers.

Information campaigns can still go a long way: the more people know about the virus, the better they can protect themselves. That is why the music that these young people are creating is so important at getting the message out there. It's also why World Vision has partnered with Hashtag Our Stories to help the kids in the settlement share their stories using smartphones — after all, that's how David was able to tell the world about these songs.

To learn more about World Vision, how they are supporting children impacted by the virus, or help in their efforts, visit their Hidden Hero page.