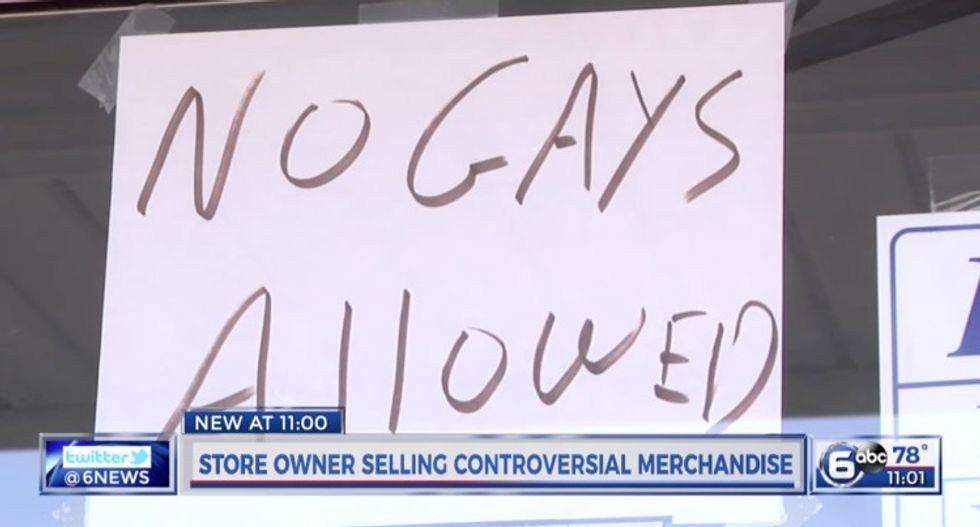

In 2015, Jeff Amyx made national headlines when he hung a "No Gays Allowed" sign outside his hardware store.

At the time, he was upset with the Supreme Court's Obergefell v. Hodges marriage equality ruling. "It goes against my religion and what I believe. I'll never accept it," he told USA Today, on his decision to ban gay people from shopping at his store.

Within a few days, in response to backlash, the sign came down in favor of one that said, "We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone who would violate our rights of freedom of speech and freedom of religion."

In the wake of this week's Masterpiece Cakeshop SCOTUS ruling, Amyx felt emboldened to put the "No Gays Allowed" sign back up.

In an interview with WBIR in Tennessee, Amyx called the ruling in favor of a baker who refused to sell a cake to a gay couple a "ray of sunshine."

Though the ruling — which was decided on procedural technicalities involving the Colorado Civil Rights Division's investigation — doesn't actually address whether stores are allowed to discriminate against LGBTQ people, some, like Amyx, appear to view the decision as encouragement to find out what the legal limits actually are.

It's worth remembering that U.S. solicitor general Noel Francisco, arguing on behalf of the federal government in support of Masterpiece Cakeshop, suggested that stores should be exempt from anti-discrimination laws and be allowed to post "No Gays Allowed" signs. Press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders agreed at the time.

While some downplayed the Masterpiece case because a wedding cake seemed like such a specific example, Amyx and others are showing just how far the "religious liberty" argument could go.

High school teacher John Kluge recently claimed it is against his religious beliefs to refer to transgender students by a name other than the one they were given at birth. "I'm being compelled to encourage students in what I believe is something that's a dangerous lifestyle," he told IndyStar.

He was fired for refusing to follow that simple rule, but plans to appeal on the grounds that his religious beliefs give him the right to discriminate against those students.

Jack Phillips, owner of Masterpiece Cakeshop. Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images.

Responding to a discussion about the Masterpiece decision on Facebook, South Dakota Rep. Michael Clark said that religious beliefs should exempt business owners from all sorts of non-discrimination protections.

Asked whether he'd agree that someone should be allowed to ban people of color from a store based on religious views, Clark said, "He should have the opportunity to run his business the way he wants. If he wants to turn away people of color, then that [is] his choice."

He later walked back this statement.

The right to practice and observe religion is an essential part of American life, but it cannot be a "get out of jail free" card.

Right now, it's LGBTQ people who are being discriminated against under the justification of "religious freedom," but we've seen this play out before.

Interestingly, it was a statement from a commissioner in the Masterpiece case that both explained the past use of ad hoc religious beliefs to justify horrific actions and helped hand the case to the plaintiffs:

"I would also like to reiterate what we said in the hearing or the last meeting. Freedom of religion and religion has been used to justify all kinds of discrimination throughout history, whether it be slavery, whether it be the holocaust, whether it be ... We can list hundreds of situations where freedom of religion has been used to justify discrimination. And to me it is one of the most despicable pieces of rhetoric that people can ... use their religion to hurt others."

The court wasn't too fond of the final line about using religion to excuse blatant discrimination as "one of the most despicable pieces of rhetoric." The truth is, however, the commissioner was right: People often do hide behind their religious beliefs — or invent new ones — to justify existing prejudice.

SCOTUS has even ruled on this before. In the 1968 Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises case, SCOTUS heard an argument for a religious exemption from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 based on restaurant owner Maurice Bessinger's "religious belief" that races should not mix.

50 years later, it seems absurd that somebody would argue that their religious beliefs should exempt them from race-based protections in civil rights laws; but as history has shown, this is a well-worn tactic that shifts from group to group over time. Courts must recognize that these arguments are frivolous and debase actual religious teachings.

Luckily, there are things we can all do to help out in the fight for justice and equal treatment under the law.

First, financial support to groups like the ACLU and Lambda Legal helps them continue the fight for equality in courts.

You can also find out who your state and local representatives are and let them know that you want to make sure all people are protected under these local laws. One of the only reasons the Masterpiece case made it to SCOTUS was that Colorado has explicit protections for people on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Many states don't.

Photo by Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images.

Finally, contact your state's representatives and senators and ask them to support the passage of the Equality Act, which would end a lot of ambiguity over whether businesses are allowed to discriminate in whom they serve.

It's easy to see stories about people like Amyx and his "No Gays Allowed" sign and feel discouraged about the future, but it's important to remember that those people are in the minority. A recent Reuters/Ipsos poll found that 72% of people surveyed around the country don't believe businesses should be allowed to use religious beliefs as an excuse to exclude entire groups of people.

This is good news and should inspire us all to get involved.