France’s rehabilitation program turns prisoners into farmers, equipping them with jobs and housing

No bars, just goats, gardens, and a second chance at life.

Moyembrie is changing inmates' lives for outside living.

Imagine a prison without bars. The cells are private rooms with doors that lock, and inmates hold their own keys. Social workers replace guards. For some, this may sound impossible, but two hours from Paris in a quiet French village, it exists.

La Ferme de Moyembrie is a working farm that doubles as a prison. It's a pioneering prison farm that challenges traditional ideas of incarceration. Here, the focus shifts from punishment and confinement into something much more meaningful: dignity, responsibility, and the heartfelt belief that everyone deserves a chance to rebuild their life.

For the men who arrive here—many after years in conventional prisons—Moyembrie offers something radical: trust. At Moyembrie, these men work the land, care for animals, and slowly remember what it's like to be regarded as humans who are responsible, dependable, and honest. It's a sanctuary where they can rediscover their self-worth, reconnect with nature's soothing rhythms, and prepare to step back into a world that too often leaves them behind.

A safe haven born from compassion

The story of Moyembrie began in 1990, not as a government program but as a personal mission. Jacques and Geneviève Pluvinage, two retired agricultural engineers, invested their life savings into the 24-hectare farm in Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique. Their plan was straightforward: give people a place to land when they had nowhere else to go.

Jacques had volunteered in prisons and had seen what happened to inmates after release: the panic, the paralysis. He began receiving letters from inmates desperate for support as they reentered society. In response, he and Geneviève did something unusual: they invited them in. The men lived in their house, ate at their table, and worked the fields alongside them.

By the early 2000s, the French justice system took notice. A progressive judge encouraged the farm to formally accept inmates serving sentences but eligible for "placement à l'extérieur" (work release). Moyembrie transformed from a shelter into a professional reintegration facility, but it never lost its sense of community. Today, it stands as proof that rehabilitation succeeds best in a supportive and collaborative environment, not behind bars.

Breaking the mold: no cells, no guards

The first thing you notice at Moyembrie is the absence: No barbed wire. No watchtowers. No scary guards in uniform. It's a working organic farm bustling with activity, the kind you might pass on any country road without a second thought.

The 20 or so men living here aren't just inmates. They're employees and community members. They hold the keys to their own rooms—a small but meaningful gesture that restores the privacy and autonomy lost in traditional prisons.

Security isn't enforced with bars; it's built on trust. The staff are social workers and technical supervisors—not corrections officers—who are there to guide and support, not to watch. This relationship sends a clear message: "I believe you are more than your worst mistake."

Finding purpose in the soil

The residents at Moyembrie wake early. From 8 a.m. until noon, they're busy in the fields or workshops, tending to goats and chickens, cultivating organic vegetables, and producing fresh cheese and yogurt.

The work is hard. It's repetitive. It's the kind of labor that makes your back ache and your hands feel like sandpaper. But it's real. Vegetables grow. Goats, eventually, will need milking. Cheese must be made.

The farm pays them a small wage and sells their produce at local farmers' markets. The economic element is just a bonus, though. The work—tending to something outside yourself, being responsible for something alive, something fragile—changes the way you relate to your own life. On a deeper level, this work can be exquisitely therapeutic.

"Work is about relearning essential life skills like punctuality or decision-making," says Leila Desesquelle, one of the nine members on the farm. "In detention, the smallest choices were made for them. So it's a big deal if they can decide on their own."

You learn to show up on time. Work with other people. Begin to see your hands as tools of creation, not destruction. There is a profound sense of healing that comes from nurturing a living thing and watching it thrive.

At lunch, everyone sits together—staff and residents share the same table. There is no hierarchy, no separation. It's just lunch.

The afternoon then shifts into personal growth. The men work on the mechanics of reentry: getting a driver's license, familiarizing themselves with their paperwork, and learning how to open a bank account or apply for housing. Some take creative writing classes. Others meet with social workers to discuss what comes next.

These afternoons are when residents learn to manage their independence, a skill that's been eroded by years of incarceration. Whether they're taking a workshop or working with social workers to secure health insurance and ID cards, every task is a step towards successful reentry.

"I used to cry when I received judicial letters because I couldn't understand what they meant," explains Mahamady. Originally from Mali, he spent seven years in French jails before arriving at the farm—without ever learning the language.

Reasons to Be Cheerful reports that Mahamady took his first French lessons in detention, then continued with bi-weekly classes at the farm. He eventually passed a French language certification test.

The power of a second chance

Does it work? In France, recidivism, or the rate at which people return to prison, is notoriously high. Reports say that two out of three people leaving prison in France will be back within five years. Moyembrie's numbers tell a different story. While exact statistics for the farm are difficult to pin down due to its small size, one report estimates that only 7% of the men who pass through the farm return to prison.

Part of that's due to structure. Before leaving, the farm ensures every resident has a safety net: their housing is pre-arranged. Most have jobs or find employment within three months. These are the building blocks of a functioning life—practical victories, the ones that make all the difference when you're starting over with nothing.

However, Moyembrie's success is best reflected in personal stories rather than just statistics. It shows up in the man who spends his weekends with his daughter, trying to rebuild their relationship.

Olivier, a former resident who now works at the farm as a counselor, credits Moyembrie with changing his life. "I lost so much during my years in prison, including my family," he said. The farm's relaxed, welcoming environment made visits with loved ones easier, helping to heal old wounds. "Slowly, we became close again."

Why we need more places like Moyembrie

Despite its undeniable impact, Moyembrie is still a rarity in the prison industry. The farm can only take in about fifty people a year, and must turn away many more applicants than it can hold

It's a double-edged sword. The program's effectiveness lies in its small scale; the deep personal bonds between staff and residents are at its heart.

Still, the idea is spreading. Since 2018, similar farms have opened across France, including a dedicated site for women. They call them "farms of hope"—living proof that justice, healing, and growth over time can go hand-in-hand, and that simple punishment isn't always the answer.

What Moyembrie shows is simple: prison doesn't have to be about punishment. Instead, it can provide people with the tools they need to rebuild and move towards a brighter future. As Christian, a former resident, describes his experience:

"After prison, you start from scratch. Everything has to be done again," he exclaims. "I had a job, a partner... I lost everything in prison. My son was born during my incarceration; I didn't know him. After that, we have to rebuild everything. It's not easy."

Then, while reflecting on his time at Moyembrie, Christian continues, "I found moral support and a family atmosphere. I went back to work like a normal guy. At the end of my sentence, I became a supervisor. I wanted to thank the Farm for all the help it had given me, and to show the residents that we can get out of it."

- How a group of 'badass' nuns became the heart and soul of a beloved Los Angeles film festival ›

- Cyntoia Brown, who murdered her sexual abuser at 16, released from prison and will now help other girls like her ›

- These amazing handmade crafts were all designed and built by prisoners seeking new skills. ›

Student smiling in a classroom, working on a laptop.

Student smiling in a classroom, working on a laptop. Students focused and ready to learn in the classroom.

Students focused and ready to learn in the classroom.

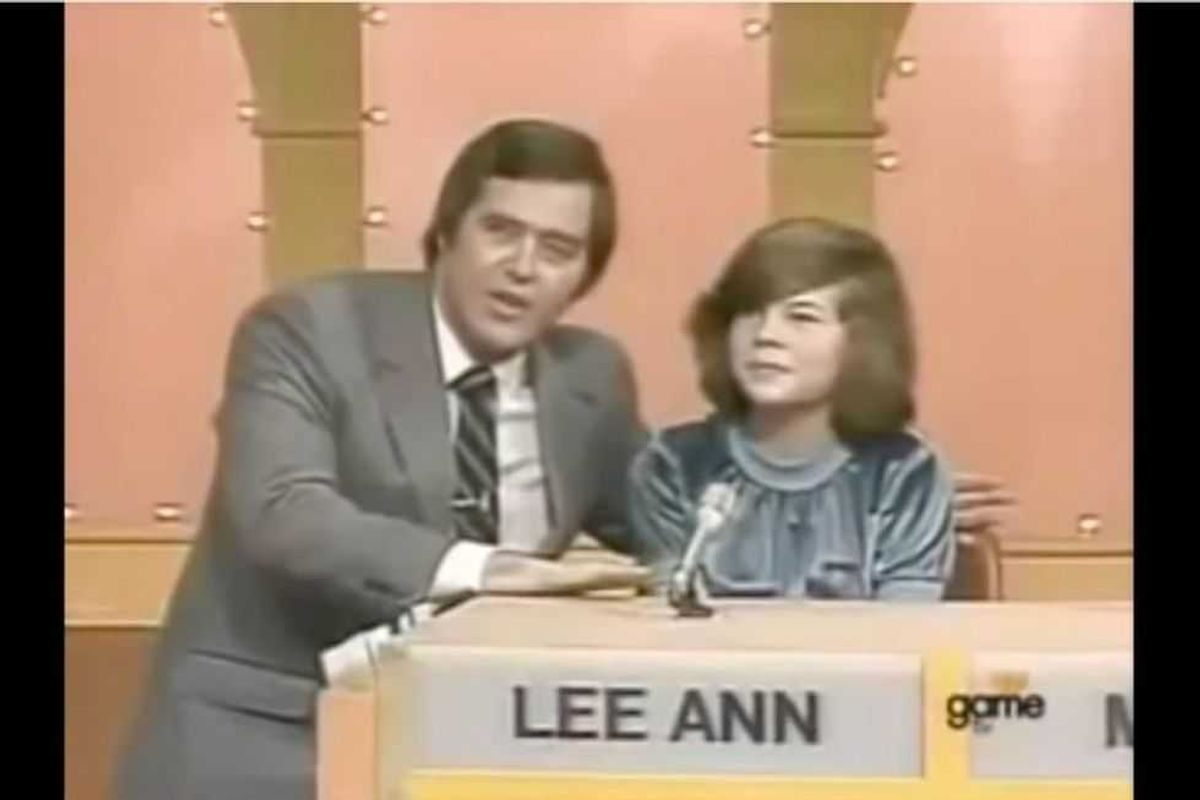

A game show host from the 80s was famous for making girls uncomfortable under the bright lights of the stage. Photo by

A game show host from the 80s was famous for making girls uncomfortable under the bright lights of the stage. Photo by  Still from the 1980s gameshow "Just Like Mom" YouTube Screenshot

Still from the 1980s gameshow "Just Like Mom" YouTube Screenshot

Fish find shelter for spawning in the nooks and crannies of wood.

Fish find shelter for spawning in the nooks and crannies of wood.  Many of these streams are now unreachable by road, which is why helicopters are used.

Many of these streams are now unreachable by road, which is why helicopters are used. Tribal leaders gathered by the Little Naches River for a ceremony and prayer.

Tribal leaders gathered by the Little Naches River for a ceremony and prayer.

It's an odd way for a friendship to begin.

It's an odd way for a friendship to begin.

Hearing people mispronounce words can be a pet peeve.

Hearing people mispronounce words can be a pet peeve. Mispronouncing words are hard to hear.

Mispronouncing words are hard to hear.