People have been singing “O Holy Night” as a Christmas standard for well over a century, and yet most of us have only ever heard the first verse. In fact, it’s likely that most people aren’t even aware that there are two verses beyond the final “Oh, night divine,” and fair to guess that most don’t know the third verse contains a blatantly anti-slavery message.

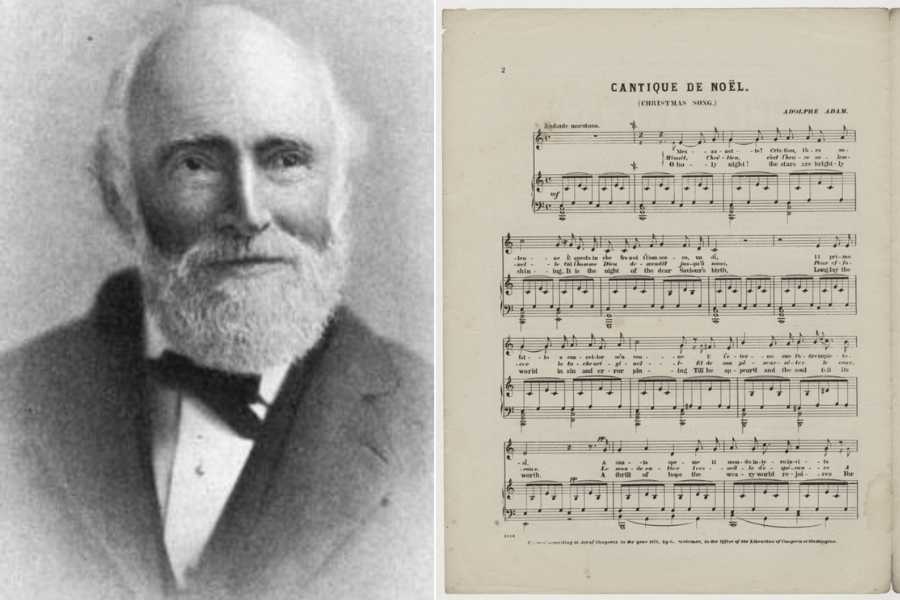

“O Holy Night” originated as a poem written by French leftist wine merchant, Placide Cappeau, before it was set to music by secular composer Adolphe Adam in either 1843 or 1847. The carol, known as “Minuit Chrétien” (“Midnight, Christians) or “Cantique de Noël” (“Christmas Hymn”) in French, sings of Christ’s birth and the visit of the three wise men in the first two verses. However, the third verse translates directly from French as such:

The Redeemer has overcome every obstacle:

The Earth is free, and Heaven is open.

He sees a brother where there was only a slave,

Love unites those that iron had chained.

Who will tell Him of our gratitude,

It’s for all of us that He is born,

That He suffers and dies.

However, American music critic John Sullivan Dwight first translated the carol into English in 1855, and he chose a more poetic, emotional wording for the entire song. His version of the third verse goes like this

Truly He taught us to love one another;

His law is love and His gospel is peace.

Chains shall He break, for the slave is our brother,

and in His name all oppression shall cease.

Sweet hymns of joy in grateful chorus raise we,

let all within us praise His holy name.

“Chains shall He break, for the slave is our brother and in His name all oppression shall cease” was quite the statement to make in the mid-19th century United States, where civil unrest over slavery would soon reach its peak. It’s no wonder that Dwight, a Unitarian minister and staunch abolitionist, was keen to bring the song to the U.S. and share it in his magazine, Dwight’s Journal of Music. According to America magazine, Dwight had written publicly about the “three or four millions of our human brethren in slavery” calling it “moral suicide” for the United States. Thus, his English version of the carol became a holiday favorite, particularly among Americans in the North in the Civil War years.

However, back home in France, the song was having a moment with the Catholic church. Cappeau, the poet who wrote the lyrics, ended up renouncing Christianity and joining a Socialist movement. The composer, Adam, was of Jewish descent, and that combination wasn’t exactly viewed as ideal for a song about the origins of the Christian faith. Additionally, official publications of Catholic music criticized the song’s “militant tone and dubious theology.” It ended up being banned in churches for years, but that didn’t seem to impact its popularity.

The idea of “O Holy Night” being in any way “militant” in tone may seem confusing if you’re only considering the English version. But again, Dwight took liberties with his interpretation in ways that don’t fully reflect the direct translation from French. Here is how the familiar first verse directly translates from French compares to the way Dwight rewrote the lyrics in English (in parentheses):

Midnight, Christians, it’s the solemn hour, (O holy night, the stars are brightly shining;)

When God-man descended to us (It is the night of the dear Savior’s birth.)

To erase the stain of original sin (Long lay the world in sin and error pining,)

And to end the wrath of His Father. (Til he appeared and the soul felt its worth.)

The entire world thrills with hope (A thrill of hope, the weary world rejoices)

On this night that gives it a Savior. (For yonder breaks a new and glorious morn!)

People kneel down, wait for your deliverance. (Fall on your knees! O hear the angel voices!)

Christmas, Christmas, here is the Redeemer, (O night divine! O night when Christ was born!)

Christmas, Christmas, here is the Redeemer! (O night divine! O night, O night divine!)

Perhaps it’s not egregiously militant, but the direct translation does have a bit more of a “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” feel to it than the softer, more poetic American version.

Why do we not hear the second and third verses of the song, though? Part of it might be the anti-slavery messaging not being widely accepted in the Southern U.S. It also might have to do with the song’s length. This version of the carol that includes all three verses is seven minutes long:

Whether we sing the whole song or not, “O Holy Night” remains a widely beloved classic, even topping ClassicFM’s list of most loved Christmas carols in 2023. It is fascinating to know that there’s so much more to it than the version we most often hear, though.