Nature

Featured Stories

Nature

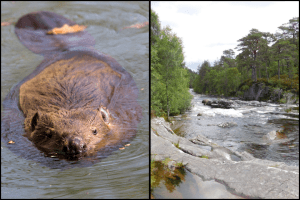

Beavers were brought to the desert to save a dying river. 6 years later, here are the results.

Their engineering feats are pretty dam incredible.

The Latest

Get stories worth sharing delivered to your inbox.

Advertisement