Dietrich Bonhoeffer argued that stupidity is more dangerous than evil. He was right.

The anti-Nazi theologian explained that stupidity doesn't mean a lack of intellect and why it's harder to battle than malice.

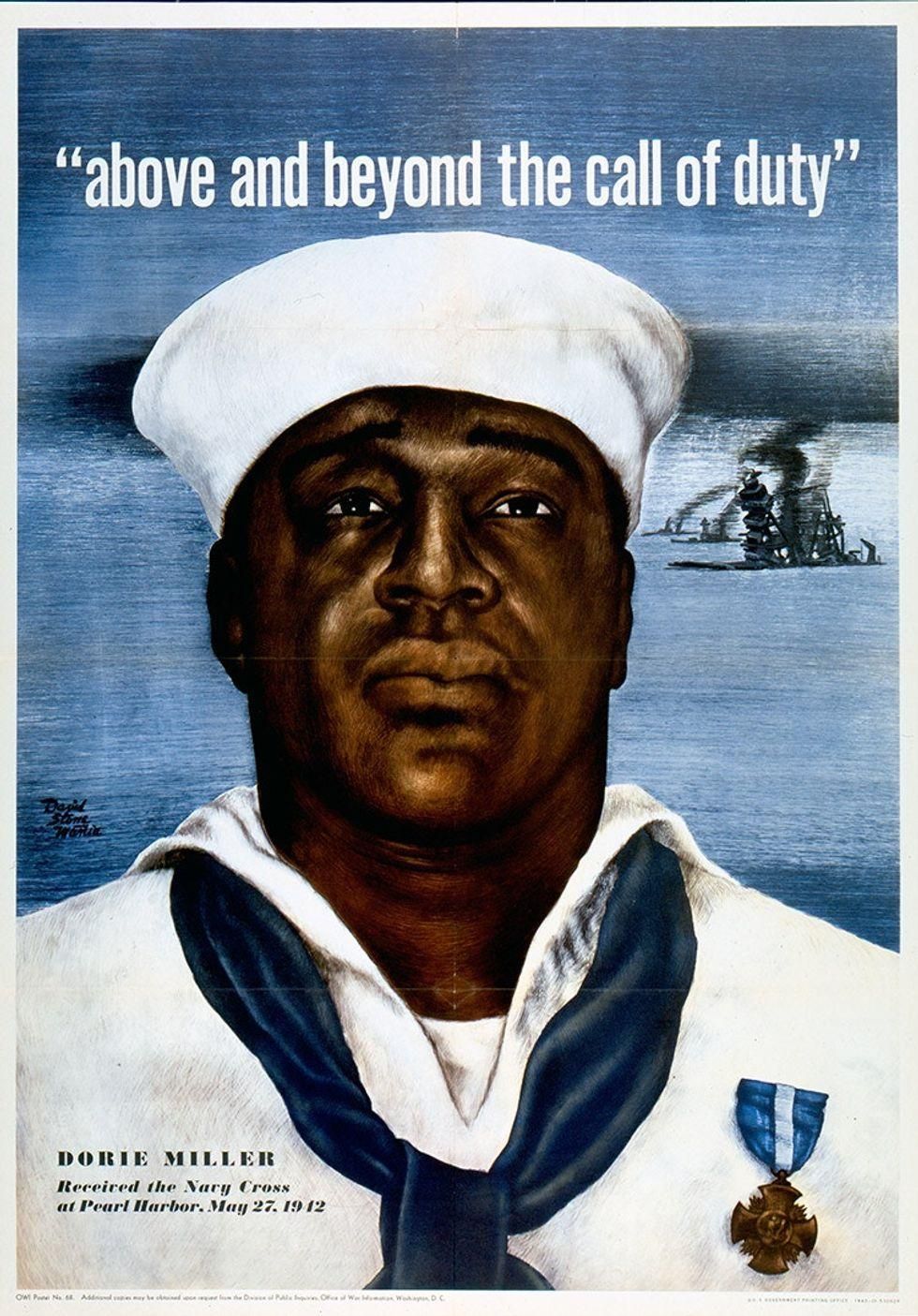

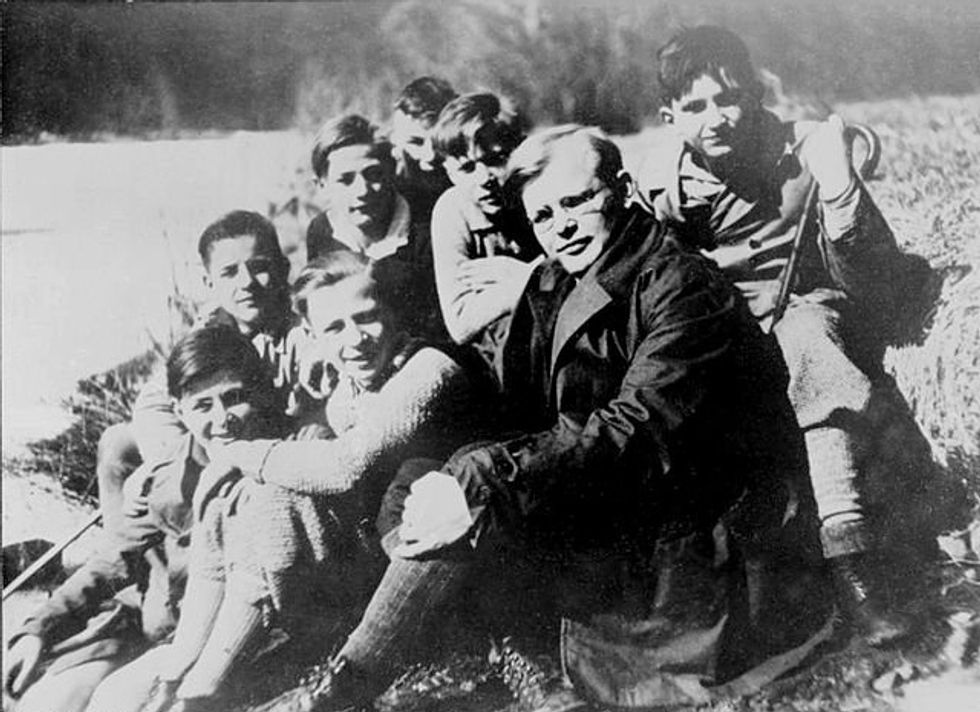

Holocaust memorial in Budapest, Hungary (left), Dietrich Bonhoeffer with religious students in 1932 (right)

When a formerly thriving nation finds itself in the clutches of a totalitarian demagogue, the question of how it happened is always foremost in reasonable people's minds. The "how" question is particularly important to ask when an authoritarian doesn't take the reins of power by force, but rather gathers enough support that people hand those reins over freely.

For instance, the infamous mass-murdering dictator Adolf Hitler was freely elected by the people of Germany, which was arguably an enlightened, artistic, progressive society at the time. To answer the question of how Hitler came to power and how people went along with unspeakable atrocities, anti-Nazi theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer posited a theory: It's not that a wide swath of his fellow countrymen were evil, it's that they were stupid. And stupidity, he argued, was more dangerous and harder to battle than actual evil or malice.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

"‘Stupidity is a more dangerous enemy of the good than malice," the Lutheran pastor wrote in his letters from prison. "One may protest against evil; it can be exposed and, if need be, prevented by use of force. Evil always carries within itself the germ of its own subversion in that it leaves behind in human beings at least a sense of unease."

"Against stupidity we are defenseless," he went on. "Neither protests nor the use of force accomplish anything here; reasons fall on deaf ears; facts that contradict one’s prejudgment simply need not be believed — in such moments the stupid person even becomes critical — and when facts are irrefutable they are just pushed aside as inconsequential, as incidental. In all this the stupid person, in contrast to the malicious one, is utterly self-satisfied and, being easily irritated, becomes dangerous by going on the attack. For that reason, greater caution is called for than with a malicious one. Never again will we try to persuade the stupid person with reasons, for it is senseless and dangerous."

But what exactly does it mean to be a stupid person in this context? Bonhoeffer said stupidity wasn't about someone's intellect, but about their social behavior and tendencies.

"There are human beings who are of remarkably agile intellect yet stupid, and others who are intellectually quite dull yet anything but stupid," he wrote. "We discover this to our surprise in particular situations. The impression one gains is not so much that stupidity is a congenital defect, but that, under certain circumstances, people are made stupid or that they allow this to happen to them."

Stupidity is more of a sociological problem than a psychological one, Bonhoeffer said, explaining that people who are independent loner types are less likely to fall to stupidity than highly sociable people. He also posited that a rise in power tends to correlate with a rise in stupidity:

"Upon closer observation, it becomes apparent that every strong upsurge of power in the public sphere, be it of a political or of a religious nature, infects a large part of humankind with stupidity…The power of the one needs the stupidity of the other. The process at work here is not that particular human capacities, for instance, the intellect, suddenly atrophy or fail. Instead, it seems that under the overwhelming impact of rising power, humans are deprived of their inner independence and, more or less consciously, give up establishing an autonomous position toward the emerging circumstances."

In other words, when a leader gathers power, whether by force or coercion or convincing people through propaganda, stupidity follows. And though it tends to be a social phenomenon, there are signs of stupidity in people that are recognizable, Bonhoeffer explains.

"In conversation with him, one virtually feels that one is dealing not at all with a person, but with slogans, catchwords and the like, that have taken possession of him. He is under a spell, blinded, misused, and abused in his very being."

Which leads us to what makes stupidity the most dangerous trait of all:

"Having thus become a mindless tool, the stupid person will also be capable of any evil and at the same time incapable of seeing that it is evil. This is where the danger of diabolical misuse lurks, for it is this that can once and for all destroy human beings."

Bonhoeffer, a theologian to the end, contended that "the internal liberation of human beings to live the responsible life before God is the only genuine way to overcome stupidity," and he also offered some hope: "…these thoughts about stupidity also offer consolation in that they utterly forbid us to consider the majority of people to be stupid in every circumstance. It really will depend on whether those in power expect more from people’s stupidity than from their inner independence and wisdom."

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was arrested by Hitler's Gestapo in 1943 after helping a group of 14 Jews escape to Switzerland. Allegedly, he played some part in a failed plot to assassinate Hitler and was sentenced to death. At 39 years old, he was executed by hanging at Flossenburg concentration camp on April 9, 1945, just 11 days before it was liberated by U.S. troops.

You can read Dietrich Bonhoeffer's "Theory of Stupidity" here.

Chicken Soup GIF

Chicken Soup GIF  No Drama Allblk GIF by WE tv

No Drama Allblk GIF by WE tv  No Way Wow GIF by RatePunk

No Way Wow GIF by RatePunk  Reduce Climate Change GIF by INTO ACTION

Reduce Climate Change GIF by INTO ACTION  Jennifer Love Hewitt Graduation GIF

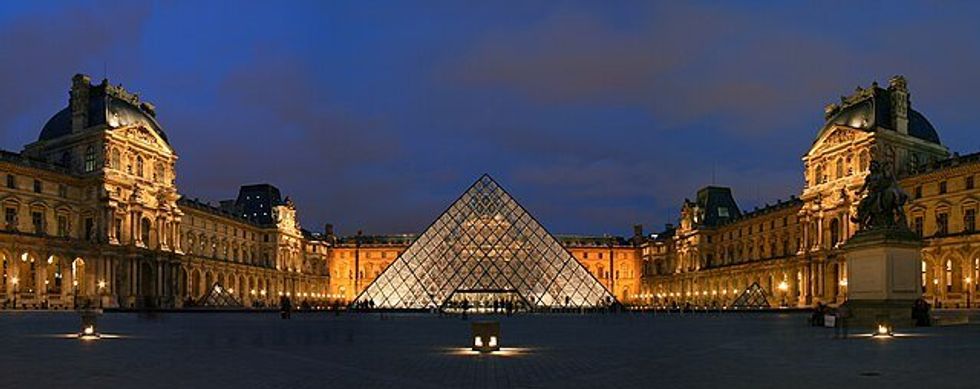

Jennifer Love Hewitt Graduation GIF Today, the "Mona Lisa" sits safely behind glass at the Louvre.

Today, the "Mona Lisa" sits safely behind glass at the Louvre. The Louvre was first built in 1793.

The Louvre was first built in 1793. Christopher Plummer and Julie Andrews on location in Salzburg, 1964

Christopher Plummer and Julie Andrews on location in Salzburg, 1964